Back to top: Part I Chapter 3

3.1 Alteration as an External Form of Control

The alteration of nature was a stricking aspect resulting from the great transformations explained in Chapter 2.

One instance of such a process is the production of artificial artifacts (cf. below 3.4), such as the operation of knapping of flints in the Paleolithic (for which see CAR, Wynn 1989, with the related Excerpts, about the concept of “spacial competence”); in this case, the object produced by human hands (with a previous “para-perception” of the resulting tool already in mind), is still recognizable even if it has been physically transformed (also under an ontological perspective: a flint becomes a tool).

Even though, in this later phase, objects are sometimes no longer recognizable, being strongly re-shaped (and shifted from a semantic field to another: e.g., a “settlement” becomes a “village”); this implies three fundamental aspects:

- the production of tools is now time related;

- the awareness of this mechanical process of production (the chaîne opératoire already discussed in Chapter 1.4) increase the role of “para-perception”: a daily-life gesture/activity in now regarded as systemic; it is the new concept of a system, which also requires a specific apprenticeship (on this topic, see Kelly Buccellati 2012 Apprenticeship; cf. also Chapter 1.9);

- this alteration means now to “create” something that had never existed before in nature.

The whole process led to a psychological attachment which developed the awareness that there are no limits or boundaries to experimentation; the notion of progress is born.

This sense of progress can be exemplified by three moments in this new dimension of human life:

- the intervention into natural processes (agriculture and farming);

- the construction of the environment (stones and bricks in function of residential buildings);

- the production of wholly artificial objects (ceramic and metal).

Back to top: Part I Chapter 3

3.2 The Alteration of Natural Processes

Cf. Chapter 1.5.

From the new understanding of territory (cf. Chapter 2) two phenomena emerged (already started in the Paleolithic and then better re-defined in the Neolithic):

- agriculture;

- domestication.

These phenomena are usually tied together under the label of “agricultural revolution” (on this topic, see e.g. Bellwood 2004 Farmers)

This “revolution” is strictly connected to the concept of territory, since it depends on a clear delimitation of specific spaces addressed to specific purposes (fields, enclosures, etc.); as a consequence, landscape changed even visually: the sense of boundaries (cf. Chapter 2.3) allowed the creation of new artificial horizons built on the human vision of the reality.

A new ability of control over nature grew up and developed inexorabily in a sense of domination which also implies the capability, so to speak, of “foreseeing the future” (as predictable, i.e. the competence of predictability [cf. below 3.6]), in the meaning of having plans for future in anticipating the needs for farming and breeding animals, having also the possibility of influencing the animal procreative system, in order to get food from them (furthermore, animals become part of the new human artificial landscape).

The control over these natural phenomena led to an increasing in the awareness of the collective and individual psyches, as a driving force for affirmation and progress.

Increasing production led to an inaspectable food surplus which forced a demographic development and make a differention of human groups possible, two factors involved in the transformation of society into hierarchical structures (cf. below, 3.8).

In the beginning, this process (from the “Neolithic revolution” onwards) was unintentional but deeply effective, as a result of the development of new para-perceptual capacities.

Back to top: Part I Chapter 3

3.3 The Built Environment

Cf. Chapter 2.2.

Shaping space according to human needs implies that human habitat assumed new physical and totally anthropic forms (the built environmentNote 1), such as that of the village which shows an organicity of the settlement (cf. Chapter 2.2). Furthermore, new structural models developed, a clear sign of a wide-ranging transformation in action, to organize the physical space.

Typical construction materials are stone (in the North, conceived as a component adapted in a physical whole and not existing in nature as a single entity, i.e. blocks, as in the Neolithic site of Göbekli Tepe, on the earliest “shrines”, in Turkey [see e.g. Schmidt 2011 Costruirono]), and mudbricks. This latter construction material is more modest (even if it is very time-lasting in good weather conditions) but, at the same time, more easily managed and shaped, for sure less expensive than stone: for all these reasons, mudbricks became the more suitable material for more complex buildings (such as temples and palaces, but even storerooms and, later administrative archives).

A very important example of mudbrick architecture and village structuring in the Neolithic is represented by the site of Çatal Höyük (in Turkey, for which see Mellaart 1967 Catal, Balter 2005 Catalhoyuk, and Hodder 2010 Emergence, along with the related Monograph), where we can found both closed spaces (rooms used as houses or shrines), characterized by an “agglutinative planning” with the access from the roofs, together with open spaces (courtyards; on this topic, and the possible function of these open spaces as ante litteram “proto-squares” see De Pietri 2014 Piazza).

Villages started emerging as physical entities, a phenomenon comparable to the alteration of natural processes (above 3.2), where the reconfiguration of the relationships with nature was definitely acquainted: “The environment is now constructed from the bottom up. […] The sense of dominance over nature is affirmed even further: the stability of residence is now borrowed from the ability to construct, to model space and volumes at will” (Buccellati, Origins, p. 31).

Back to top: Part I Chapter 3

3.4 The Production of Artificial Matter

Cf. on this very topic, Wynn 1989 and (even partially) Cauvin 2000.

Cf. above 3.1.

The production of new material is another aspect of the development described above: ceramic (made of clay, temper elements, water) and metal alloys are not present in nature as final artifacts and the human craftsmanship granted the creation of new “row” materials; the homo faber was “born”: men “created” new substances previously not existing. This also led to the invention of new structures such as the kilns to fire the pottery or the crucibles and the furnaces to forge and melt metals.

The “invention” of ceramics also entangles a more profound and “spiritual” meaning (for the concept of spirituality [cf. below 3.6] as defined by G. Buccellati, look at Buccellati 2023, in Mes-Rel): in fact, in the Enūma elī#353; – the Babylonian creation poem (for which see e.g. Lambert 1968 and Lambert 2013, in Mes-Rel)– creation is described as a process of “morphing” (the same that we also find in Gen. 2:7), essentially a mythical and aetiological projection of the great transformations of this period (and even this projection is a result of human “para-perception”).

The development of pottery-making had two other important (both utilitarian and aesthetic) effects:

- the possibility of boiling liquids;

- the birth of the concept of artistic artifact (since ceramics is very often decorated) and, as spring for it, an “artistic mind” (in which is embedded an inner sense of beauty); it was, in a nutshell, the origin or art [for which see the companion website Mes-Art].

The production of metals or metal alloys was more complex and had strong impacts on the relationships between the first societies: “An important moment in this process of experimentation was the discovery of ways of producing the alloys of different metals, particularly copper and tin to produce bronze. The motive was that of obtaining a better consistency and therefore duration in the final result. This was especially important for the new use for which the product was destined from the beginning, that of the production of weapons. Therefore, this was the first artifact for hunting and especially for war, derived from a substance obtained through a chemical process” (Buccellati, Origins, p. 33).

In this late Neolithic time, more elaborated metal tools shifted from a hunting purpose to war aims: it was, in a way, the birth of a new concept of warship (of course, struggles and fights between different human groups were already existing; even though, the use of metal weaponsNote 2 deeply changed the approach to fights, now becoming proper wars).

Back to top: Part I Chapter 3

3.5 The Development of the Manufacturing Process

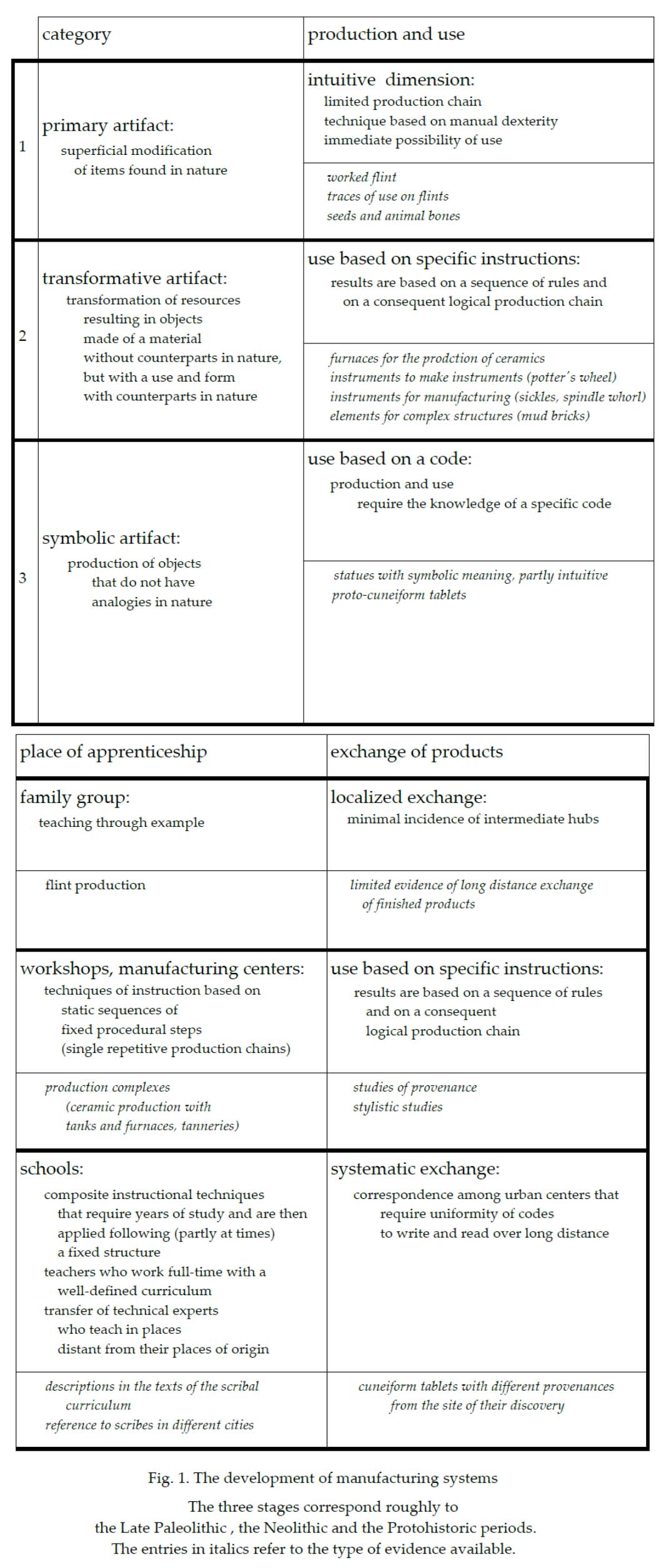

The devoloping of manufacturing process, a momentous transformation in human social dynamics, can be briefly summarized into three core phases:

- raw materials still retain their specificity, being just modified to obtain usable objects, but they still maintain their “matrix” (a flint is a flint, even it is artificially modified);

- raw materials are transformed creating a new matrix further shaped into specific forms (from clay pottery is crafted and from ores metals are molded);

- crafted artifacts have no longer analogy in nature (cf. Chapter 4)

The complexity of this process is characterized by three particular features:

- the way in which the objects are produced and used under an intuitive level;

- the way in which the relative technology is transmitted;

- the way in which the objects produced are exchanged from one group to another (i.e., the background for barter at first and trade later on).

Furthermore, this process, becoming more difficult and specialized (as already stressed, cf. above, 3.1) requires a specific apprenticeship, since such a specializationNote 3 requires a specific traineeship and a practice continuous in time.

In the end, the surplus of food and the production of crafted materials exceeding the needs of a singular community slightly led to the formation of the notion of market and the creation of short and long-distance trade.

All the aforementioned considerations are summarized in the following table:

Back to top: Part I Chapter 3

3.6 The Ideology of Control

Cf. Chapter 2.1 and Chapter 2.6.

The notion of control implies not only the transformation of the natural environment, which acquires the state of a built environment (cf. above 3.3), but also a different way of reconfigure perceptually and conceptually the landscape as a para-perceptual superstacture of the human mind: the construction of society (Chapter 1), the invention of territory (Chapter 2), and the alteration of nature (present chapter) in the first Axial Age (Chapter 1.2) show how human beings recreated their external world according to parameters anchored in they internal way of para-perceiving things.

All in all, “the application of mechanisms of control meant developing precise criteria of predictability” (Buccellati, Origins, p. 37; cf. above 3.2), a phenomenon rooted in the “discovery” of a (perceptual rather than conceptual) notion of causality.

In this perspective, we have also to take into consideration the development of religious attidudes (cf. also Mes-Rel, Chapter 16): we could think of religion as the institutional codification of intuitions derived from spirituality (cf. above 3.4), a process linked to the perspective of control described above: “the predictability inherent in psychological processes that I have just described could extend itself ad infinitum, and therefore, precisely, to the “comprehension” of not just finite and concrete reality but also of a reality hidden and operative, operative as far as it is seen as the ultimate source of limits. This is the absolute” (Buccellati, Origins, p. 37; on the concept of absolute, see the dedicated monograph in Mes-Rel; cf. also, for the concept of “absolute” Buccellati 2024 When, section 3.4).

Back to top: Part I Chapter 3

3.7 Political Ideology

The ideology of control (above, 3.6) is strictly involved in the development of political ideology/ies; the shifting of human groups from the level of community to that of society (cf. Chapter 2.6), along with the capacity of control leading to the knowledge of operative systems (above, 3.1), contributed to the formation of a new social environment.

“Political ideology is based on an analogous conception of the relationship between individuals as components of a new structure – to be exact, society” (Buccellati, Origins, p. 38); a balanced measure of control, made stronger and more effective thanks to the food surplus and manufacturing operations (above, 3.5), increased the functionality of the social group.

From this new re-shaped social groups, leading individuals emerged as leaders: it was the beginning of the ideology of command and leadership, whose forms of control are not necessarily coercitive. A very common image for these leaders is that of the shepherdNote 4, attested several times in Mesopotamian literature (see e.g. Westenholz 2004 Shepherd and Anthonioz 2020 Shepherd; cf. also Ivy Ewald 2010 Shepherd) and iconography (see e.g. here, from Sumerian Shakespeare). His task was, as already stressed not cohercitive, but had mostly the purpose not of “forcing the flocks” but rather of leading and pasturing them, securing thir defence; the ruler was in charge first to care of his people.

Back to top: Part I Chapter 3

3.8 Authority and the Emergence of Hierarchy

Thank to the aforementioned dynamics, organizational skills emerged and improved in time, as a driving force to development.

Archaeology helps us in understanding this phenomenon of progressive social stratification, specifically in the following spheres:

- tombs (with different funerary equipments);

- differentiation of habitations;

- appearance of complex structures requiring explicit planning.

All these aspects are related to different levels of he common dimension of control (above, 3.6).

Besides, or better along with, this phenomena, also the concept of authority was set on stage: “What happens when “society” comes into existence is that the appearance of para-perceptual structures involves reserved spaces that exist, through their own nature, independently from the presence or absence of people meant to carry out a particular function. […] And this is also an example of how an elementary experience [find reference] […] is institutionalized in concrete forms autonomous from original experience. Here we are confronted very explicitly with the transformation of perception from a primary level (personal authority) to one that is secondary or super-sensory (institutional authority)” (Buccellati, Origins, p. 39; cf. also Chapter 5.14).

Back to top: Part I Chapter 3

Notes

- Note 1: for the definition and principles of the “built environment”, see the Urkesh website, section Mozan Sitewide. Back to text

- Note 2: the value of metal weapons had a long-lasting history (and story): just think of the situation told by Homer in his Iliad (whose story is allegedly situated in the Late Bronze Age, i.e. ca. 1500-1200 BC), where in many passages (particularly on the occasion of interchanging the own weapons after a fight or an important deal between two heroes) the weapons of the Trojans (maybe already of iron and sometimes, at least according to Homer’s narrative, of gold) are more valuable (and stronger) than the Achaeans’ ones (still produced in bronze); see e.g. the famous episode of Glaucus and Diomedes in Il. 6, 235. Back to text

- Note 3: this specialization, along with the food surplus (leading to the redistribution system attested archaologically by the so-called “bevelled-rim bowls”; see e.g. Millard 1988 B R B), will be the core incentive towards the formation of a hierarchical society (cf. above 3.8). Back to text

- Note 4: the image of the leader as a shepherd was long-lasting in time and widespread in the ancient Near East cultural milieu: it will be sufficient to recall here the application of this image (and imagery) to Mesopotamian gods (like Dumuzi [see on Mes-Rel, Alster 1972, Alster 2006, and Xella 2001]), to the God of Israel (see e.g. Ps. 80:1) and later to Jesus described as the “Chief Shepherd” (see e.g. 1Pet. 5:2-4); on this topic, see specifically Westenholz 2004.

A text describing the king as shepherd is, e.g., the composition about the Kassite king Agum-Kakrime and the return of Marduk, for which see Foster 20053, pp. 360-364 (cf. related Excerpt). Back to text

Back to top: Part I Chapter 3