Back to top: Part II Chapter 6

6.1 The City-State as a Nuclear Territorial State

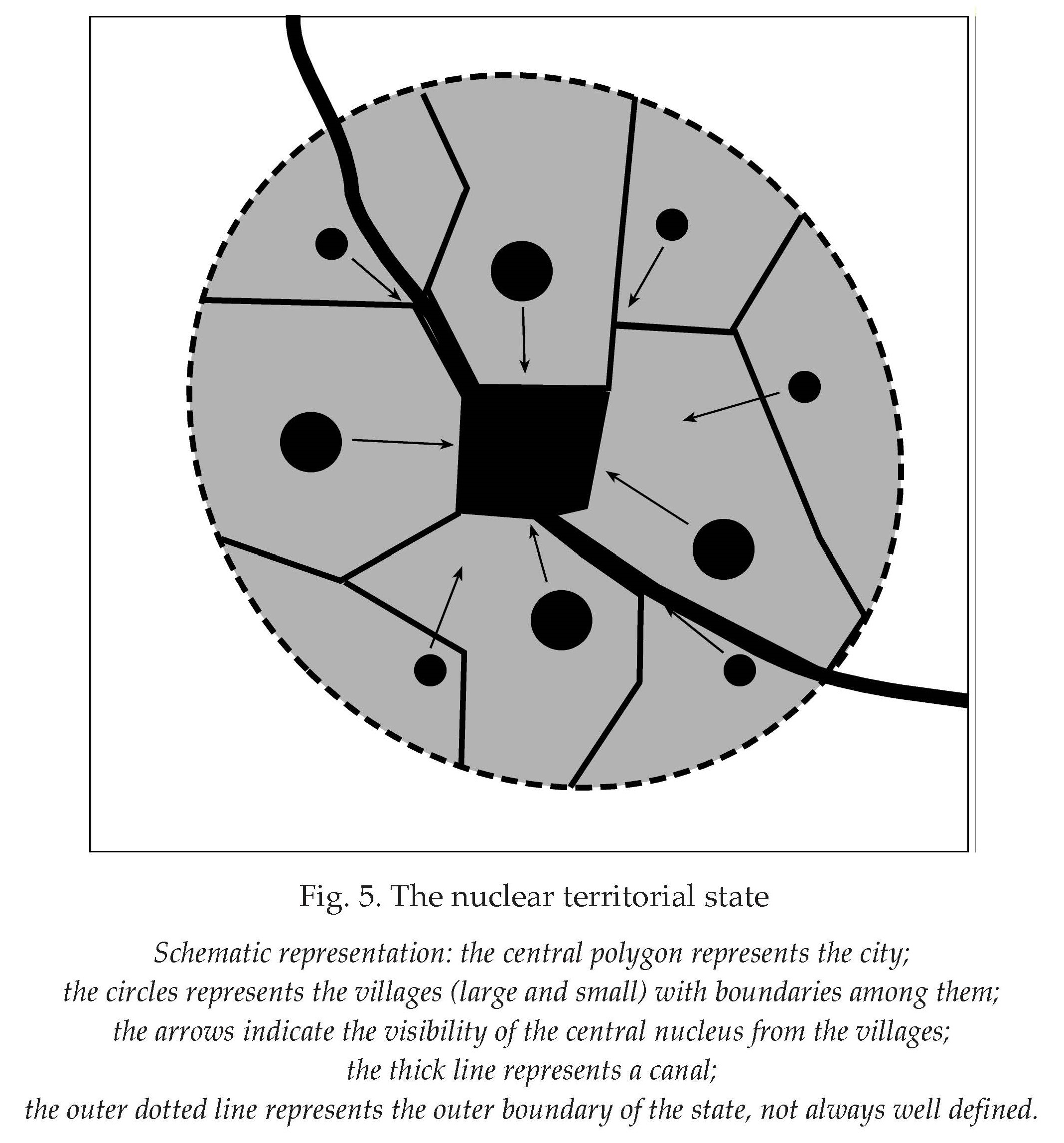

The model of the state in ancient Mesopotamia was focused on an urban settlement which is the center of the state as a physical element: it is commonly labeled as “city-state” (or better “state-city”, stressing its political dimension), but it would more appropriate to define it as “nuclear territorial state”, underlining its structural dimension, an organism where territory unifies the social structure as a single great nucleus.

The territory (cf. Chapters 2.3, 2.5, and 5.4 about the territory in relation to villages) in the state-city shows a physical continuity of the inhabitants which is defined by an architectural horizon (cf. Chapter 5) consisting of two elements:

- the monumentality of the urban nucleus as a central point of reference;

- the material demarcation of the boundaries (cf. Chapter 5) of the land around the villages.

The following Figure 5 graphically explains this dynamic:

The demarcation of boundaries at the sime time divides the lands (as separated, singular plots) and unifies the lots (as a coherent whole belonging to the state as coordinating organism). Even lands physically far from the center can experience a kind of virtual visibility of the monumental core, thus maintaining a face-to-face association with the territory.

Back to top: Part II Chapter 6

6.2 The Territorial Foundation of Solidarity

As already stressed (Chapter 5.16), the word “politics” comes from the Greek term πόλις, “city”: the nuclear state is like a formal prototype of the state (including its institutionalized institutions) in a general sense.

The small dimensions of the nuclear territorial state underlines a strict relationship between the limitation of territory and the perceptual identification of the inhabitants with it, an identification which brings about a sense of solidarity (cf. Chapter 2.5); in this regard, also the surrounding countryside forms a single entity with the city, since visibility of the central nucleus is (more than a mere symbol) a constant perception of the central axle. Specific structures, like the ziggurats (in the South; cf. above Chapter 5.4) or the temple terraces (in the NorthNote 1), represented an example of these structural elements of reference to the central core.

This strong relationship to territory is evident also in the concept of “motherland” embedded in the Sumerian and Akkadian words for “country”, kalam and mātum, respectively, a concept which remains for centuries a key word to refer to territory as a political and social reality (cf. below, for the meaning “people”).

Furthermore, the was also a sense of kinship relationship to territory (a parent for the social group), clearly expressed in the use of Akkadian syntagms like mārū ālim (Akkadian) = dumu.meš uru (Sumerian), to define “citizens”, literally “sons of the city” (cf. below, and (conversely) mārū ugārim (for which cf. also Mes-Rel, Chapter 22.7, note a.) to qualify the “peasants”, literally the “sons of the irrigation district”Note 2 (cf. below Chapter 16.4, with Figure 7).

This physical contiguity within a common organism extends to the hinderland the concept of family: the state is encased in the physical reality of the territory (as family relationships are encased in the physical reality of the house), deeping the sense of solidarity (since the state is like an “extended household”) which will be surviving also the explosion of territories, the formation of the new concept of “capitals” (cf. Part III), and the relative automy of some cities (cf. Chapters 19.2-19.3).

Back to top: Part II Chapter 6

6.3 The Role of the Temple

At the summit of the city there was the temple of the principal deity (the polyad deity, for instance NERGAL = Kumarbi at Urkesh; see Buccellati Kelly Buccellati 2009 Temple, section 7) of the town. This location clearly states the importance of religion as an expression of self-identity and integration of the people living in the city.

The temples also had an economic implication, since they developed a great bureaucratic and administrative system implying importance economic resources. Even though, the temple did not retain a specific role in terms of politics, since the “Palace” remained distinct from the “Temple” as place of royal authority. The importance of the temple in politics could be affected and overestimated (because of a biased archaeological inference) by the fact that many cuneiform administrative archives were located within the temple precint, even if the temple did not play a key role in the structure of the political system.

Back to top: Part II Chapter 6

6.4 Politics and Religion

On religion, see in detail Buccellati 2024 When; cf. the dedicated companion website Mes-Rel; cf. also Chapter 5.6.

On this very topics (i.e., the role of religion in politics and the impact of spirituality on politics), cf. also the excerpts from Buccellati 2024 When.

Despite what said above, there were for sure relationships between political and religious dynamics, specifically for what concerns ideological aspects (for which see Buccellati 2024 When, chapter 16). In fact, “politics and religion reflect two ways in which society conceives of the absolute. Religion looks to define the very nature of the absolute and the modalities with which we can relate to it. Politics looks to define the social group as an autonomous and self-governing entity, “absolute” therefore in the sense of that sovereignty (5.6) that represents all the nodes of power into a single apical point […]” (Buccellati, Origins, p. 81).

The difference between the political and the religious absolute (for which see the related monograph in Mes-Rel) resides in an asymmetrical parallelism: in fact, while the latter is perceived as an outside source of control over the world, the former is constructed within the world; the political absolute basically acts to guarantee the continuity of power; it is the absolutist pretense of the state, capable of keep control over strong centrifugal tendencies, thanks to two models/paradygms which could resemble, in a way, controversial but they were not percevied as such (rather in a complementary sense):

- that of sovereignty, absuming the incarnation of the absolute;

- that of limitation of sovereignty within the sprehe of the state-city, implying a “virtual” sovereignty which was indeed very realistic.

The state was proposed an an alternative religion, in the sense that the state did not use religion instrumentally, but as an system alternative to religion as such.

Back to top: Part II Chapter 6

6.5 State and People

“The notion of the “social group” is an abstraction, but one that refers to a very concrete reality, the “people.” It is a collection of individuals who are connected by that para-perceptual “tensionality” that I described above (1.3) and recognize one another as members as a single political body” (Buccellati, Origins, p. 82). Later on, the concept of individual, and in effect of the person, will be rediscovered in terms of political reality (cf. Chapters 16.6-16.7).

In the Mesopotamian nomenclature there is a marked conceptual categorization: the Sumerian un.meš equivalent to the Akkadian nišū, meaning generally “people”; another expression having a strong political (and even geographical) connotation is the Akkadian ṣalmāt qaqqadim (corresponding to the rare Sumerian sag.ge6.ga), meaning “black of heads”, that is “civil humanity” as a whole.

As already seen the terms for “country” (cf. above), Sumerian kalam and mātum (Akkadian), also meant (synecdocally) “people”.

Other terms related to population are “men (lú.meš in Sumerian and awīlū in Akkadian) of GN”Note 3 and “sons (dumu.meš in Sumerian and mārū, cf. above, in Akkadian) of GN”.

In effect, the name of the city, al also the term mātum was regularily used to express the concept of “state”, since there is no specific term in Sumerian or Akkadian for “state” (see Preface) and neither the term for “kingship” (Sumerian nam.lugal and Akkadian šarrūtum; cf. 5.10) can be interpreted in this sense.

Usually, the name of the most important city, like Bābilim for Babylon and Aššur for the Assyrian “empire” (another concept which does not have a term in Mesopotamian languages), remained central for many centuries, even thought there are a few exceptions of terms of political realities transcending proper names of cities (cf. Chapters 10.4, 18.3, and 20.4).

Back to top: Part II Chapter 6

6.6 A Universe of States

The Sumerian city of Uruk [cf. below] emerged as the greatest in terms of geographical expansion; even though, despite the so-labeled “expansion” or “colonization” of Uruk (cf. Chapter 8.6), this city was very likely not chronologically the earliest model, since the coherent formula of the territorial state widely diffused in different areas at the same time.

This is manifested by a clear similarity between institutions (not excluding local differences) for what concerns:

- type of government (e.g., the use of Sumerian terms for “king”, i.e. en, ensi, and lugalNote 4, etc.);

- religion (e.g., the deitis chosen for each city pantheon, etc.);

- scribal schools (e.g., the calendars, the metric systems, etc.).

On the one hand, small structural differences allow us to exclude a processes of “colonization” in which all the “colonies” share the system of a single mother city; on the other hand, the structural similarities are overarching, at the point that we can rightly speak of a Mesopotamian cultural ecumene (cf. Chapter 8.2), showing a deep internal coherence, specifically in two aspects:

- “the coexistence of these ‘sovereign’ states juxtaposed against each other contributed to create a truly international order (also in case of conflicts, like the one between the king of Lagash (cf. below) Eannatum and UmmaNote 5 […];

- a perception also developed of the essential homogeneity that extended beyond the confines of the individual states and thus showed the wider horizons of a fully shared culture, in open and explicit contrast with the non-culture of those beyond these horizons – the “barbarians”” (Buccellati, Origins, p. 84).

All in all, the structure of these first territorial states shows:

- a very complex system of balances;

- that there is no apical point above the sovereign states (either being those nuclear or explanded; cf. Chapter 7.1);

- the presence of different dynamics and stimuli to expansion, triggered by the aforementioned system of balances (cf. Chapter 8).

In the following sections, some peculiar aspects of homogeneity (6.7-6.9) and differentiation (6.10-6.11) will be further outlined.

Back to top: Part II Chapter 6

6.7 The Politicization of the Pantheon

The deities chosen as patrons of a city usually differed from those of other cities; nonetheless, they were related each other in an organic system based on kinship, being part of a pantheonNote 6, a term which we can understand in a double sense:

- it was the result of a “theological” organization as a logical construct;

- the deities were not only iconically identified with natural phenomena (tempests and groundwaters, sun and moon) but also tied to specific points of the new human geography.

In a city where there was a major deity, such as Enlil (for whom see Mes-Rel) at Nippur (cf. below), it was possible that also other deities were worshiped, despite the prominence of the patron deity, which meant to things:

- the principal temple was dedicated to that deity;

- there was a certain exclusivity in the association of a patron deity to a specific city.

“What is significant […] is that this prominence can be seen as the reflection of the system of balances […] above. The political dimension of the pantheon, therefore, is an indication of a certain interurban awareness, capable of underscoring the integration of different elements in an organic whole […]” (Buccellati, Origins, p. 85).

Back to top: Part II Chapter 6

6.8 The Political Imaginary

We are not sure that names of cities attested in the fourth millennium BC remained the same also in the third millennium BC; despite the fact that it is very likely, this must be kept in mind in defininf the self-identification of the social group as such.

As a consequence of the aformentioned interurban awareness, it is important to raise the question if a supra-urban awareness was already existing in the fourth millennium BC; the correlation between the pantheon and its political substratum reflects a political imagination uniting state-cities under a common ideological awareness possibly resulting also in a political connection among states (cf. Chapter 8.7.2), maybe even in the form of an aggregative federation strengthened by a strong supra-urban awareness.

We could have two clues for this:

- a type of seal with a series of cuneiform signs (sometimes in a very well-executed calligraphic taste), each one of which stands for the name of a city (we could compare, in a way, these seals with the tablets, also known as “abecedaries”, with the list of the Ugaritic pseudo-alphabetic signs, in the second millennium BC; cf. Chapter 17.8);

- the already mentioned Sumerian King List which, despite its final composition dates back to the besinning of the second millennium BC, still reflects a so well-articulated conception that it seems likely that it had already been developed in the more archaic periods. In this composition, the core is that the institution of kingship is a single one at time: “The ideology of kingship is therefore singular and gives diverse historical realizations something like a chrism of authority. The canonization of Mari within this list is particularly significant in this regard because of the relatively late chronological position of this kingdom and because of the considerable geographical dislocation (6.11.2)” (Buccellati, Origins, p. 87).

Back to top: Part II Chapter 6

6.9 A Differentiated Homogeneity

The “city” did not exist as an abstract entity, but each city developed through the second half of the third millennium BC in the Syro-Mesopotamian area, showing a series of singular concrete historical realizations (cf., about differentiation, (6.7-6.9), unified in a explicit unitary dimension (cf., about homogeneity, (6.10-6.11).

“In the same way, therefore, these specific nuclear states were part of a complex network resting on reciprocal equilibrium, which highlighted both their differences and their similarities. It was a simultaneously coherent and variegated universe. […] We may define this as a differentiated homogeneity” (Buccellati, Origins, p. 87).

In this process, two dichotomous dynamics development, i.e. those of two centrifugal and centripetal forces; the state is the historical realization of this process.

The basic difference resides in the distinction between nuclear and expanded states (cf. Chapter 7).

This situation will change only with the development of the imperial strategy (cf. Chapter 23) which nevertheless presents itself “as the recovery of a global homogeneity capable of cancel ling out local differences” (Buccellati, Origins, p. 88).

Back to top: Part II Chapter 6

6.10 The Fourth Millennium

In this section, some relevant historical concretizations of the “urban experiment” of the fourth millennium BC will be outlined, highlighting some salient characters of each specific state-city (their proper and differented physionomies); similarily, in the following section (6.11), an overview on similar processing occurred in the third millennium BC will be sketched.

In following chapters (8.2-8.2), instead, the attention will be focused on different factors behind the curtain of the urban phenomenon.

Back to top: Part II Chapter 6

6.10.1 Uruk – The Vastness of the Settlement

Uruk was indeed the most important of the archaic Sumerian city (cf. e.g., Liverani 2006 Uruk) and, because of its rich archaeological and textual evidence, it gave the label of one of the great divisions discussed above (cf. Chapter 5.19). It has been also considered as the cradle of the cultural irradiation involving the whole Syro-Mesopotamian area (on this topic, cf. below Chapter 8.6).

The city is also mentioned in the literature of later periods as the seat of Gilgamesh (see e.g., George 2000 Gilgamesh and George 2003 Gilgamesh; cf. also the related Excerpt), leading campaigns against Agga of Kish (for which cf. below) and Enmerkar of Aratta (in modern Iran) and also fighting other mythological figures which represent, in the language of the myth (for which cf. Mes-Rel), the effort to locate different “foreign” landscape in the conceptual map of the surrounding world.

Back to top: Part II Chapter 6

6.10.2 Nippur – The Navel of the World

Nippur, differently from Uruk, did not represent the seat of a specific king (either historical or mythological); in fact it is absent from the Sumerian King List, and the title “King of Nippur” is never attested (in fact, the archaeological excavations led there had never found a royal palace).

The city emerges instead as a pivotal point in geo-cosmic conception of the world, a kind of “umbilicus mundi” ante litteram: dur.an.ki in Sumerian, i.e. “the bond between heaven and earth” (cf. also Mes-Rel).

Thus, as a kind of anomaly in the process described above, Nippur was basically and intrinsecally a religious center; nonetheless, the city played an important political role, under two respects:

- it was the site that legitimized the political hegemony of other cities;

- it is possible that it exercised a certain political role as the center of a league of cities (cf. Chapter 8.7.2).

Back to top: Part II Chapter 6

6.10.3 Kish – The Structural Basis of Hegemony

Kish took, in a way, the hegemonic role of Uruk at ca. the end of the fourth millennium BC; four specific political point can be stressed:

- the Sumerian King List places Kish in a prominent position as the first city to have a royal dynasty after the flood (for which see Mes-Rel);

- the very first texts of a purely political nature come from Kish, in particular the first Sumerian royal inscription (for which see C D L I, RIME 1.07.22.02) of king Enmebaragesi (see Michalowski 2003 Enmebaragesi), father of Agga;

- the city appears in a series of descriptions of conflicts between cities, partly legendary;

- a king of Kish, named Mesilim acted as an arbitrator between two southern cities, Lagash and Umma (cf. above).

“[…] these are the most apparent traits of a structurally expansionist tendency (8.7.3) […] all of which contributes to defining a very special physiognomy of this city. Partly because of the fact that the first empire comes out of Kish ([…] Chapter 9.3), the title of ‘King of Kish’ will remain canonical for the rest of Mesopotamian history […]” (Buccellati, Origins, p. 90).

Back to top: Part II Chapter 6

6.10.4 Ur – Luxury as a Correlative to Power

Ur is particularly relevant (specifically from the end of the Early Dynastic period) for an aspect of these first great urban complexes: together with Ebla, it is the site where the most considerable quantity of metals and precious stones were found, coming largely from a royal “cemetery” (see e.g., Woolley 1934 Ur); they are an archaeological evidence for the opulence of the families of dead people.

After all, the city was an important commercial center, considering its position as the principal port to the “lower sea” (the Gulf), thus towards the South-East; furthermore, objects coming from Ur were uncovered in cities to the North-West, like MariNote 7.

Back to top: Part II Chapter 6

6.10.5 Lagash – Temple Administration and Populism

Lagash, modern al-Hiba (but cf. 8.7.1), like Ur was located in the area of the Gulf but more to the North; here, the archaeologists retrived the most relevant documentation, dating to the Early Dynastic period, about temple organization (see e.g. Oppenheim 1944 Temple and Sterba 1976 Management) for the supervision of production and redistribution of products.

This prominence of the temple seems to be confirmed by the fact that at Lagash the sovereigns carry the title of ensi instead of lugal (cf. above) and also because Lagash is absent from the Sumerian King List.

Even though, this stress on the temple is likely too strong, probably because the emplacementNote 8 of the administrative texts is within the temple archives.

Abother important fact is that at Lagash we see the first attempt at codifying in writing a collection of observations trying to define abuses of a system of regulation to correct it; it was the so-called “reform” of Uruinimgina (or Urukagina), inscribed on some cones (see e.g. AO 3149 at the Louvre) found at Girsu/Tello, city ruled by Uruinimgina/Urukagina (reigning in the 24th century BC).

Back to top: Part II Chapter 6

6.10.6 Nagar – At the Center of the ‘Upper Country’

The “upper country” (mātum elītum in Akkadian) refers to the naturally fertile plain “upstream” (hence “upper”) on the irrigable plain (southern Mesopotamia).

The differences with the South are considerable, not just in terms of geography (cf. 8.2) but mostly under a specific political aspect: it was in fact there where the first expanded states developed (cf. 7.1). Thus said, in the same territory there were also examples of nuclear territorial states, with important monumental buildings (Habuba Kebira, in the West and Tepe Gawra, in the East) and great extension of the settlements, like Hamoukar and Nineveh (both in the East).

Nagar, modern Tell BrakNote 9, is situated in the center of the fertile plain in the North, with great dimensions already reached by the second half of the fourth millennium BC.

Peculiar finds and material culture from Tell Brak, especially from the so-called “Eye-Temple”, show local traits but also elements hinting to a strong connection to the South.

The geo-political horizons of the city seem restricted to the surrounding plains, without extending to the mountains, the Jebel Sinjar in the South or the Tur Abdin in the North. In this phase Tell Brak was still a nuclear territorial state; even though, near to that city, one of the most important expanded territorial states developed: it is Urkesh/Tell Mozan (cf. 7.6.1; for this city, see the dedicated website).

Back to top: Part II Chapter 6

6.11 The Early Third Millennium

The first urban foundations of the early third millennium BC, mostly in the North, were not immune to the first urbanization (cf. Chapter 8.3).

Thus stated, we have also to consider that for at least two cities of this second phase we have evidence of non-urban settlements from the fourth millennium BC, close to the cities of the third millennium; they are:

- Ramadi (near Mari/Tell Hariri; cf. below);

- QrayaNote 10 (near Terqa/Tell Ashara, for which see the dedicated website; cf. also Buccellati 1990 Terqa).

Tell ChueraNote 11 (cf. below, instead, seems to represent a new urban foundation on a settlement of the fourth millennium BC after a period of abandonment.

It is not clear if these sites were new territorial states or rather expanded territorial states (cf. Chapter 7); for a possible hypothesis about a development of these sites from a city developing a sense of supra-urban superiority, cf. below Chapter 7.1.

Back to top: Part II Chapter 6

6.11.1 Eshnunna – The Relevance of the Territory

Eshunna, in the Diyala river valley, is the most important of the four sites excavated there from 1930 onwards, being the capital of that region in the latest periods (cf. Chapter 7.1).

Two aspects of these excavations must be emphasized:

- the stratigraphic sequences were analyzed with precision, and a typological definition was proposed (especially in ceramics) that conceptually anticipated the most refined categorizations made possible today by digital systems (see e.g. the Urkesh topical book about ceramics); as a consequence of this precise methodology, a system was proposed that pointed out the greatest distinctions based on cultural and political factors; in fact, this period has been labeled as “Early Dynastic” (sometimes abbreviated ED), a terminology based on dynasties and not on an archaeological facies;

- the extension of the interest moved from the single site to the whole surrounding region; this led the archaeologist to consider the area within a coherent territorial framework, pointing out the specific settlement patterns and the relationships of the city with its hinterland, specifically for what concerns the utilization of physical resources and the struggle against ecological problems (like the salinization of the fields, for which see e.g. Liverani 2018 Paradiso, ch. 4.7).

All in all, this led to a much deeper understanding of the very concept of the state.

Back to top: Part II Chapter 6

6.11.2 Mari – The Hinge Between Two Worlds

Mari can be considered in a way the “counterweight” of Eshunna, because the formes is located along the Euphrates, the latter on the Tigris river; but, beside this common trait, they faced two different developments.

On the Euphrates there were intermediate stations: in the fourth millennium BC, they were Ramadi and Qraya (cf. also Chapter 8.6.2); the latter was indeed very important for the production and trade of salt (cf. note 10); even though neither Ramadi or Qraya reached the status of urban centers.

At the beginnings of the third millennium BC, two ciies developed in the nearby of the aformentioned centers: Mari and Terqa. These two cities developed as key places for the trade along the two rivers, showing a peculiar commercial vocation. The plan of these cities is very regular (cf. below), hinting to a carefully developed master plan. Mari was at the beginning a nuclear state later evolving into an expanded territorial state “namely, when the agricultural sector of the population discovered the potential of the desert on an ‘industrial’ level and added a new type of pastoralism to the economic resources of the state” (Buccellati, Origins, p. 94; cf. also Chapters 7.7 and 11.1).

Despite all the differences, Mari can be included into the wider southern Mesopotamian ecumene (cf. Chapter 8.2); the “Treasure of Ur” found here is a clear evidence for this statement; in a way, Ur and Mari (the latter being the main center towards Dilmun = Bahrain, Magan and Meluhha = shores in the northwestern Indian peninsula) were the two opposite pole of the axis represented by the Euphrates.

Under this perspective, the mention in the Sumerian King List of the center of Hamazi (in the Diyala or the Zab river valley) is significant, since Eshunna is not mentioned, while Hamazi took the role of the counterpart of Mari (in the idealized vision of the king list; cf. Chapter 8.2).

“The fact remains that Mari was central to opening, both economic and cultural, towards the north and the northwest, something which profoundly defined its physiognomy. Except for details that are minor in themselves, like the use of different bricks than those that characterize Sumerian architecture in the Early Dynastic period (the so-called plano-convex bricks), there are especially close cultural ties with Ebla, with Mari serving as the key connecting point between Ebla and Kish” (Buccellati, Origins, p. 94).

Back to top: Part II Chapter 6

6.11.3 Tell Chuera – The Urban Fabric

Tell ChueraNote 12 (cf. above), ancient Nagar, started as a new foundation of the beginning of the third millennium BC, insisting in the area of a previous settlement of the fifth millennium BC (abandoned in the fourth millennium BC).

Like Mari it was centrally planned around its center, with a radial system of streets. Under this regard, the city can be considered as the first example of the so-called “crown-mound” (Kranzhügel in German, for which see e.g. Smith 2022 Kranzhugel), “a system based on pastoralism which also somehow used the open spaces within the external city walls” (Buccellati, Origins, p. 95)Note 13. The planning of the town is, in the end, quite similar to that of Mari (for town plannings in the Ancient Near East, see e.g. Lampl 1968 Cities), implying a central political control.

“Particularly significant is the fact that Ebla is the major political center of a ‘Sumerian’ stamp in the extreme northwest of the ‘other’ ecumene (8.2). If Mari was the hinge between the two worlds, […] Ebla was in a certain sense the final frontier towards the Taurus.

Back to top: Part II Chapter 6

6.11.4 Ebla – The Last Frontier

Cf. the official mission’s website; for the texts retrieved in the Ebla archive, look primarily at the dedicated website.

From the Ebla royal archive (for which see e.g. Matthiae 1995 Ebla) we have a huge quantity of documents written both in Akkadian and Eblaite, possibly attesting (along with the sure archaeological evidence) also remote contacts with Egypt of the Old Kingdom (i.e. in the first half of the third millennium BC)Note 14; the scribal protocol followed the Sumerian habit, but the social and political administration are more tied to the Semitic identity of the population, clearly reflected in the onomastics.

Back to top: Part II Chapter 6

Notes

- Note 1: see, e.g., the “Temple Terrace” at Urkesh, for which cf. Buccellati Kelly Buccellati 2005 Hurrian and Buccellati Kelly Buccellati 2009 Temple). Back to text

- Note 2: compare this term, referring to a countriside/peripheral district, with the aforementioned (cf. Chapter 5.18) babtum, “the whole of doors”, probably referring to a city/central district. Back to text

- Note 3: “GN” stands here for the abbreviation of “Geographical Name”. Back to text

- Note 4: the three terms usually translated as “king” more precisily refers to three different roles or features of the “king”: en is the “king as lord“; ensi refers to the “king as interpreter“; lugal is the “king as ruler” (on this topic, see Rd Aonline, under entry “Herrscher A.” (by G. Frantz-Szabó); furthermore, it seems there was a geographical pattern of distribution in the use of these three terms: for instance, at Lagash it is more common to find the word “ensi” (cf. above), while at Uruk “en” is more frequent; we do also have to keep into consideration that some Sumerograms could be read in languages other than Sumerian: e.g., at Urkesh/Tell Mozan, in the cuneiform inscriptions of Atal-šen (r1) we find the Sumerogram LUGAL, while in the inscription of Tiš-atal (r2, as on the glyptics of king Tupkish) we can read the Hurrian term for “leader/ruler”, written phonetically as en-da-an (for which see e.g. Laroche 1980 Glossaire, p. 80, with reference to the term entanni, on p. 82). On these topic, cf. also Chapter 8.7.2. Back to text

- Note 5: for the texts about this war (fought ca. 2346 BC), see e.g. Barton 1929 R I S A, pp. 48-67 (some excerpts are available here); the conflict is also visually and textually told on the “Stele of the Vultures”, today at the Louvre (cf. also on C D L I, RIME 1.09.03.01). Back to text

- Note 6: on “pantheon”, cf. Mes-Rel. Back to text

- Note 7: not to be forgotten the fact that, traditionally and according to the Old Testament, Ur was the motherland of the patriarch Abraham see, e.g. de Pury 2000 Abraham; cf. also Buccellati 2007 Yahweh, pp. 296-297 [Excerpts (MES-REL)]): see Gen. 11:28ff.; on this very topic cf. Mes-Rel; for possible, even if difficult to prove, connection with Urkesh, see . Back to text

- Note 8: on the concept of “emplacement”, see the Grammar of the Urkesh website; cf. also CAR. Back to text

- Note 9: on Tell Brak see Gadd 1940 Brak, Mallowan 1947 Brak, Michalowski 2003 Brak, and Oates 1997 Brak. Back to text

- Note 10: on Qraya, an important site for production and trade of salt, see Buccellati Kelly Buccellati 1988 Qraya; Buccellati 1990 Qraya, Buccellati 1990 Salt, and Hopkinson Buccellati 2023 Qraya. Back to text

- Note 11: the precise identification of Tell Chuera with an ancient site is still debated; it has been proposed (see Pfeifer 2014 Jakob) to equate it to the ancient Ḫarbe, known in the second millennium BC by Middle Assyrian texts; as for the toponym used in the third millennium BC, it has been advanced the possibility of identifying it with Abarsal (see Archi 2021 Wars). Back to text

- Note 12: a similar structure, but for very different purposes (i.e. aggregation in a fortified citadel serving also a food production place), will be developed in the Middle Assyrian period (in the Late Bronze Age), in the form of dunnu or dimtu; see e.g. During 2015 Dunnu; cf. also During 2015 Dunnu. Back to text

- Note 13: for the possible equations with ancient toponyms, see note 11; for a history of the excavations in this site, see on ArchéOrient - Le Blog. Back to text

- Note 14: it is also important to recall here that Ebla had strong and continuous contacts with Egypt (known as dugurasu in the Eblaite documentation; see Biga Roccati 2022 Place; cf. also Biga 2024 Byblos), already in the third millennium BC; of this topic, cf. Matthiae 2018 Egypt. Furthermore, it is worth mentioning that, concerning the geographical mindset of Ebla, Urkesh is never mentioned in the Ebla archives. Back to text

Back to top: Part II Chapter 6