Back to top: Part II Section 5

5.1 The “Need” for the City

Cf. on this topic e.g. Liverani 1997, Liverani 2006.

At a certain point in Mesopotamian history, around the fourth millennium BC, the first villages (for which see Section 2.1) were re-shaped into a new reality, i.e. that of the “city”; what was the basic and substantial difference between the first stable settlements and the first cities (about this very question, see e.g. De Pietri 2014 Piazza and the related dedicated monograph)?

In a way, at a certain point of human development, people felt the “need” for the city: a new structured system including organicity (in shape) and permanence (in time) of different instances already emerged in the “pre-city” period; this was indeed a crucial, momentous time in history: “With the city, instead, all the phenomena we have seen revolve coherently and definitvely around a single axle. And at the ore of this axle there is, as we will see, political power” (Buccellati, Origins, p. 51).

That of city is a phenomenon typical of the so-called “long-duration” processes (see in detail the concept of longue durée, for which cf. Braudel 1997 in CAR); the case of city is set as a process of transformation from communities to societies, which still, nevertheless, retain their inner status of “communities of people” (see Section 1.8; cf. further Chapters 8 and 13.5).

Back to top: Part II Section 5

5.2 The City as an Architectural Whole

Cf. Section 2.6.

One of the first and most clear examples of the phenomenon described above is the Sumerian city of Uruk, located in modern souther Iraq. By many scholars (see, specifically on this topic, Liverani 2006 Uruk) it has been regarded as the “first city” (more precisely, one of the first cities in Mesopotamia, since other very old cities can be identified in the Levant, such as Jericho, for instance).

One core difference between villages and cities is the presence of a new architectural organization made evident by new buildings of monumental dimensions, attributed either to the religious (temples) or the secular (palaces) sphere. Even though, the common feature that need to be emphasized here is “the vastness and the organicity of the structures, a vastness that can be seen in the size of the footprint, and an organicity that can be inferred from the coordination and coherence of spaces and volumes” (Buccellati, Origins, p. 52).

Besides this development, also an increasing production of metals (specifically bronze) can be detected (in fact, this period is labelled, archaeologically, as “Bronze Age”, spanning ca. 3000-1200 BC; cf. Section 3.4), along with a wider spread of writing which became of systematic usage in cities (cf. Section 4); these two aspects are clearly emerging in the archaeological record.

All in all, we are facing the so-called “urban revolution” (see on this topic Childe 1950 Urban; cf. also Section 1.1).

Back to top: Part II Section 5

5.3 The City as a Logical Construct

The basic feature of what we could call a “proto-city” is that the individuals of a specific social group recognize themselves as members of a determined entity on the basis of a sense of solidarity that transcend the limit of reciprocal face-to-face recognition; and this process of formation of a para-perceptual community is again a product of the para-perception of the previous millennia (cf. Chapters 1.3, 2.6, and 4.6).

The institution is not the primary reason for people to gather into a city; instead, it is the individual who feels him/herself as part of a superstructure which framed the individuals within a predefined organism – the city – which also represent the “need” that the various para-perceptions were consolidated into a cohesive and articulated whole which appears as an autonomous reality – the society – taking the upper hand over the community.

Two particular aspects can further illuminate this phenomenon:

- the essential validation of the whole system is in its efficiency, which becomes a new criterion of value, since the great transformations seen in the previous chapter made life more productive and the demographic increase represents a clear verification of the “validity” of the city experiment;

- the disintegration of the reciprocal sense of the human face-to-face association; furthermore, alienation becomes evident in the phenomenon of slavery, since a great scalarity was introduced into the social structure, creating gaps in prestige and economic ability, expanding the sense of distance between sub-groups in the same social group.

These phenomena marked a radical rupture in the human story.

Back to top: Part II Section 5

5.4 The Para-Urban Dimension

With the first cities, villages died and the rural countryside emerging from the urban revolution was characterized by a strict relationship with the urban center: the city depends on its rural surroundings for supplies while the village (a new type of village that we can label “para-urban”) requires the urban institutions for its own survival, as in the case of the “para-scribal” situation described in Section 4.7: ‘scribalcy’, in the sense of dependence on written texts, emerges as another need, in both urban and rural areas.

Similarily, agricultural or manufactured production has its end point in the city, specifically in the urban markets; at the same time, religious techniques, religious practices (as processions or divination), and religious buildings (like the ziggurat, on which cf. Mes-Rel, Mc Mahon 2016 Ziggurat) mark the tie of the rural environment with the urban religious center (cf. Section 6.1). Another aspect strengthening the bonds between city and its rural surroundings is represented by the resolution of conflicts in the hands of judges who apply rules established by the king, perceived as the supreme judge (see e.g. the very famous “Code of Hammurapi”, for which cf. Harper 1904 Code; cf. also below, 5.8).

An example of how city impacted on the “built environment” (cf. Section 3.3)Note 1 is represented by the irrigation of the fields and the creation of canals (see Liverani 2018 Paradiso, ch. 3.5) used as arteries of traffic, which are both forms of territoriality, i.e. forms of control over nature (cf. Section 3.6).

Also important is to better define the very notion of city: “the city was not only the settlement defined by the buildings included within the outer walls, but also the whole of the territory whose boundaries were defined by the plots of lands described in contracts with absolute precision. The boundaries of the territory were the most external boundaries of the rural zones, not vaguely perceived as open spaces, but described minutely in the documents kept in the archives” (Buccellati, Origins, p. 55).

Back to top: Part II Section 5

5.5 The State

The city as described in the previous sections can be considered as a “proto-state”, defining state as “the amalgam of all the nodes of power that were articulated within the various levels of ‘society’ understood in the specific sense that explained above (2.6)” (Buccellati, Origins, p. 55).

The basic feature of this “proto-state” is that the center (the city) proposes a true level of sovereignity which is recognized to the city because of its efficiency and because of the sense of directionality deriving from it; the state is a dynamic element based on forces interacting with each other in a constant equilibrium.

Thus said, we can define the proto-state as “an articulate system of apical control of all the other elements of control within a given social group, with the presupposition of institutional permanence assumed to last for an indefinite period time” (Buccellati, Origins, p. 56).

Sovereignity and directionality reflect two particular dimensions (5.6-5.7) of the state which develops its own internal mechanisms (5.8-5.13).

Back to top: Part II Section 5

5.6 The Assumption of Sovereignty

Sovereignity is properly “the inclusivity of all the levels of power and authority, a super-level that admits nothing above it” (Buccellati, Origins, p. 56).

A specific political realism can be envisage in the coincidence of the state with the city (the so-called “city-state”) and the limits of state sovereignity can be traced in the existence of other seats of sovereignity, i.e. other city-states. Thus, the urban revolution is also a “state” revolution.

These limits in sovereignity are broken just in the case of a state expanding its boundaries to include other “sovereignities”: that is the empire, conceived as an universal state (cf. Chapters 6.4 and 13.7).

[On the concept of ‘unresolved sovereignity’, cf. Section 13.7.]

Back to top: Part II Section 5

5.7 The Directionality of Intents

Politics, understood as “control over all the lower nodes of power […], contributes essentially to maintaining a sense of solidarity within the social group” (Buccellati, Origins, pp. 56-57).

The ideological level helped in cementing the value of politics, in two specific spheres:

- political and

- religious.

“The ideological level, however intangible, is of fundamental importance and takes two forms, political and religious. Religious ideology proposes institutional ways of maintaining harmony with a dimension that looks beyond the immediacy of daily events – harmony with the absolute. Political ideology, on the other hand, is completely immersed in this immediacy, and comes to encompass religious ideology in itself” (Buccellati, Origins, p. 57).

The key element underlining the whole process is the directionality of intents: political leadership (i.e., kingship) presents specific targets to which the state can contribute for an effective realization, granting the functioning and continuity of the established order.

That of the helmsman is a perfect figure for the capacity to govern; the leader is the person in charge of hinting the target to the social group, interpreting the real needs of the state and contributing to their achievements.

Back to top: Part II Section 5

5.8 The Juridical System

Cf. Section 15.4.

Since the state displays a social structure more complex than that of personal relationships, it necessarily requires a codification of common rules: the need for “juridical codes” was an active component in the city process of development.

Three are the leading components of such a need:

- the concept of rules;

- the sense of justice;

- conflict solving.

Codes are basically a standardization, or reification, of rules into a system that goes beyond the contingent moment having the capability of predicting and forestalling; the state needed a regulatory system, reified in the form of judicial decisions; in fact, the first codes were not a mere collection of rules but rather a collection of juridical verdicts (cf. Section 15.4) regulated by a systematic and logical sequence of arguments formalized under the principle of horizontal coherence; the king delivering the code acts as a judge, under the higher level of gods’ judgments (in fact, e.g. the Code of Hammurapi begings with a dedicatory hymn to Shamash, the good judge).

In a way, it was a kind of “virtual form of rights or laws as concrete expressions (judgments) of a unitary concept (justice) set in place by a specific person (the judge). […] it is what we see in the first historical attestations of juridical situations all the way down the classical example of Hammurapi who defines his text as a collection of dīnāt mīšarim, “verdicts of justice”” (Buccellati, Origins, p. 59).

The universality of these codes derives from the empirical approach to concrete judicial cases becoming paradigms of conduct.

Back to top: Part II Section 5

5.9 Private Law: From Possession to Property

Cf. Section 2.3.

As a result of the urban revolution, in the juridical sphere, there was also a new arrangement of the, alredy existing, concept of individual possession, evolving into the idea of private property, which is no longer contingent in time as in the prehistorical period (again, an application of a para-perception).

The “right” of owning “things” came up over the stage of history; for the first time, a referential relationship between stuff and its possessor was clearly established; property became a juridical (para-perceptual) entity transcending limits in time thanks to the concept of heredity; at the same moment, however, “the deep disparity between economic position and social level developed” (Buccellati, Origins, p. 60).

The oldest example of all of this is at first land ownership, where land is confined into specific and limited boundaries and assigned to an individualNote 2.

At the end of this process, “the concept of slavery also developed, in which the para-perceptual principle of functional relationships (5.14) was applied to the human person who was reified as an object subject to juridical possession, that is, property” (Buccellati, Origins, p. 60).

Back to top: Part II Section 5

5.10 Public Law and Ideology

Cf. Section 2.2.

In the same period of the creation of private and penal law described above, it is noteworthy that public law did not shaped as well; maybe the reason for that can be found n the fact that private and penal law were defined throughout millennia, while the state was defined in a relatively brief period of time.

Even though, as seen above, the distincion between public and private had been already set up; the para-perceptual system described in Section 2.2 contributed as key factor in the formation of the state where “the “public” is precisely the supra-personal sphere that encompasses the personal portion and imposes a regulation that has its own reality” (Buccellati, Origins, p. 60).

Nonetheless, a clear regulation of the public was not established yet; some observations can be advanced:

- the super-juridical position of the sovereign guaranteed the continuity and integrity of private and penal law (the king being the supreme judge standind beyond the law);

- constitutional mechanisms will be developed only in relation with the development of the tribe (cf. Section 16.6) an example of public conflict is represented by the imposition of taxes and the related exemptions given to great landowners (cf. Section 19.3) or to cities (cf. Section 19.2).

- about transmission of power, the solution found was related to biological filiation: the dynastic system; this conception was superimposed on the state from the private model, without being formally theorized;

- there was a lack of articulated laws regulating relationships between parallel sovereignities (i.e. there was still no need for an international law); in case of conflict, the solution was the war (cf. below) leading as a consequence to the expansion of the state;

- ideology took over the role of the lacking juridical codification of power, representing in a way its substitute: the divine origin of kingship granted the rulers with a super-juridical justification; in fact the Sumerian King List (SKL) (for which see e.g. Jacobsen 1939 S K L; cf. also Michalowski 1983 History and Michalowski 2012 King) begins by saying that “kingship (nam.lugal; cf. 6.2) descended from heaven (an.ta) and goes on to cities; the Code of Hammurapi tells us about the vocation of the king set at the very beginning of history: the Enūma elīš (for which see e.g. Lambert 2013 Creation; cf. Kammerer Metzler 2012 Enuma; see also Foster 2005 Before, pp. 436ff. [see Excerpts]; cf. also notes in Dalley 2000 Myths, pp. 233-274) describes the creation of the city as a fundamental moment even earlier than the creation of humankind, because kingship was based on the state structure of the city.

Back to top: Part II Section 5

5.11 The Administrative Infrastructure

Cf. Section 4.7.

The concept of “verifiability” is important in the nature of the first texts (cf. Section 4.9) and this stresses the centrality of the administrative dimension. Writing was introduced as a tool for accountability and organizational procedures, and therefore had a fundamental role in the systematization of the state infrastructure. Writing, as an impersonal system of communication keeping trace of information, served to ensure predictability.

Hierarchy, as attested and documented by various titles of funtionaries in charge of controlling different activities, is another important feature of the first city-state experiments; the administration of the state was shaped as a bureaucratic system (cf. Section 4.8). This basically means that a communication within the new “society” developed as an articulated system of functional boundaries based on the principle of delegation of authority. This system is clearly exemplified by the use of seals and sealingsNote 3, “readable” also by illiterate people, for administrative purposes.

The state developed a series of permanent institutions with different and progressive levels of authority; at the top of this system there was the “Palace” (Sumerian e.gal = Akkadian ekallu, literally, the “great house”) understood as a legal person, synonymous with the king and his administration, ruling over the aformentioned hierarchical system without necessarily using force (cf. below).

Back to top: Part II Section 5

5.12 Industrialization of the Economy

“The formation of the state is the political dimension of the urban revolution. Industrialization is the equivalent economic dimension” (Buccellati, Origins, p. 63).

Industrialization is a para-perceptual way of connecting resources, particularly metals (and, above all, bronze which requires both copper and tin to be produced). It can be also defined as “the systematic segmentation of ways of procuring resources, producing goods and then distributing them through a prepared commercial network” (Buccellati, Origins, p. 63).

Four further consequences can be advanced:

- no single element in the production chain is able to control the entire process;

- every individual who finds himself in the segments of the system, especially at the lowest level, can be replaced with little difficulty, because of the high degree of technical specialization;

- the concept of long-term investment develops rapidly;

- the concept of interest is set in place, as a para-perceptual capacity of segmenting temporal sequences.

Another importan aspect is the disappearing of limits of the capacity of accumulating goods, leading to a radical change in the amounts of individual wealth.

As a consequence, also taxation developed as a new system of control, in both the imposition of tariffs on goods and performance of forced labor (corvée); through taxation, the Palace also increased its control and its wealth.

Back to top: Part II Section 5

5.13 Organized Use of Force

The archaeological evidence, including more sophisticated weapons, helps us in understanding that in this period a permanent and institutional military force developed; other archaeological clue for tat are the presence of city walls dating to the first half of the third millennium BC and the depictions of war operations on glyptics (along with the representation of the king as a warrior). Furthermore, from the half of the third millennium BC, we find the first texts describing wars.

It was in that time that war became part of the urban mental horizon as a normal factor of life, even if conceived in this first time mostly as a way to maintain sovereignity of individual states.

War will be also responsible (in a later period, for which see Part III) for the explosion of boundaries through true campains of expansions.

The organized use of force required a centralization of command, taking care of logistics, tactics, and strategy, in order to be able to prevent possible future dangers; all in all, the organized use of force increased the measure of the king’s control at its highest level.

Back to top: Part II Section 5

5.14 The Functionalization of the Individual

Cf. Section 5.14.

A consequence of the para-perceptual evolution, through which functional relationship between individual replaced personal relationships, was the functionalization of the person; the new society precedes and founds the individual, and the previous face-to-face relationships are re-shaped as a specific kind of social relationship where the individuals recognize themselves as part of the state.

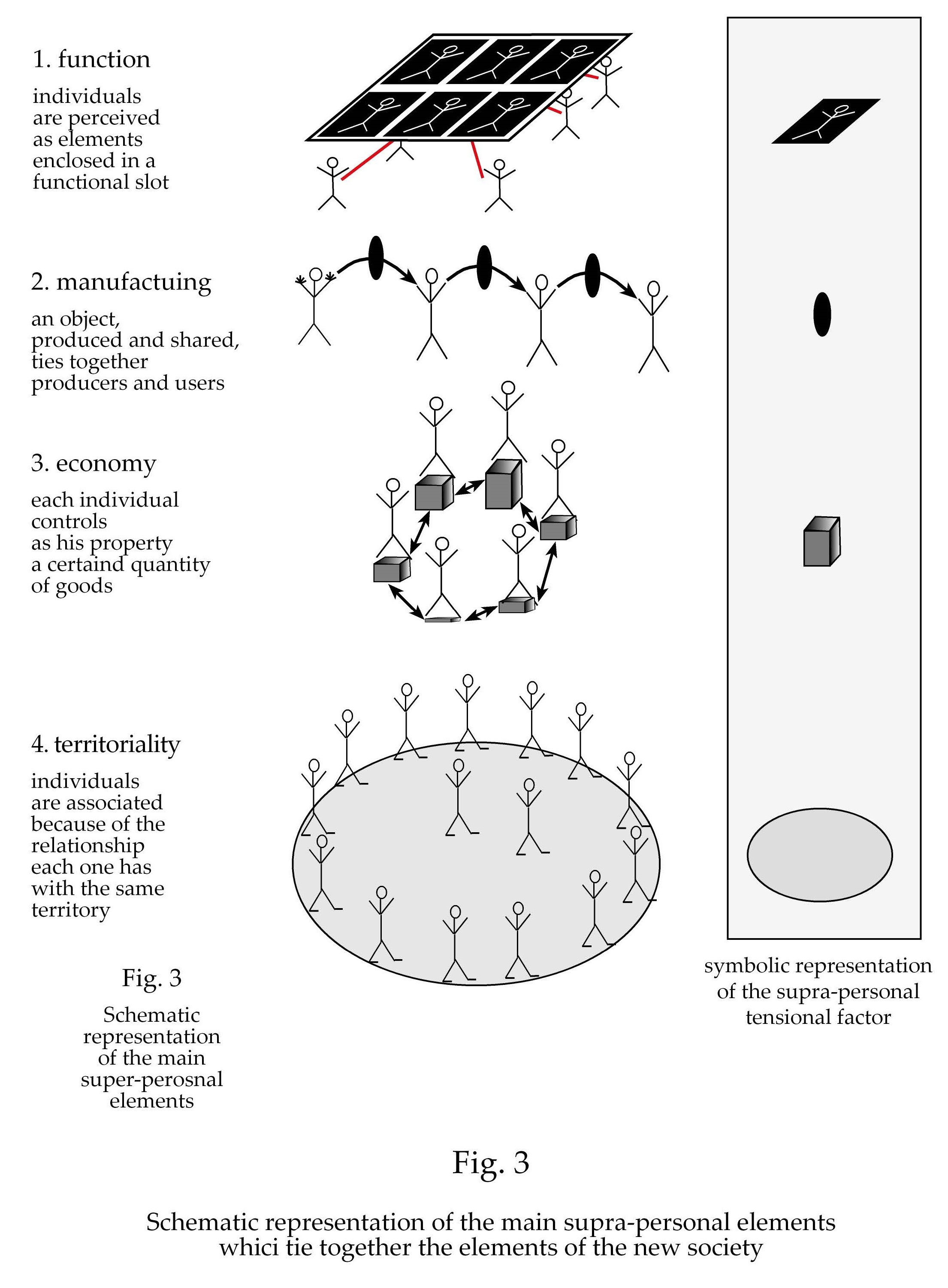

This process is graphically summarized in the following chart:

Again, we can envisage in this process another example of reification affecting the very core of the nature of human relationships: it is the system that assignes roles and finality to the individuals; a potter if a cell, a category, within a wider system (the state, displaying his self-standing complex of rules), independently from his proper name and nature; it is his functions what matters.

Another important aspect resulting from this process is the role of an increasing efficiency which is linked to a related phenomenon of losing of personal identity: man is now regarder as a component of a wider mechanism, in a process eventually ending in slavery.

Back to top: Part II Section 5

5.15 The King as Surrogate of the Personal Factor

The gap between riches and poors increased (Section 3.8), a situation idealized even in literature (see e.g. the Epic of Gilgamesh), where the position of the king is that of the maximum functional unit at the vertix of the social pyramid, as a unifying factor, even if sometimes inaccessible to people.

The figure of the king came to assume specific, idealized traits: the king as father, shepherd, advocate for people (all these are ideal paradigms, since the king became a kind of virtual person).

The king as a symbol was at the root of the development of a new royal propaganda which became a fundamental instrument of control, being him a ‘tensional’ link between individuals.

Back to top: Part II Section 5

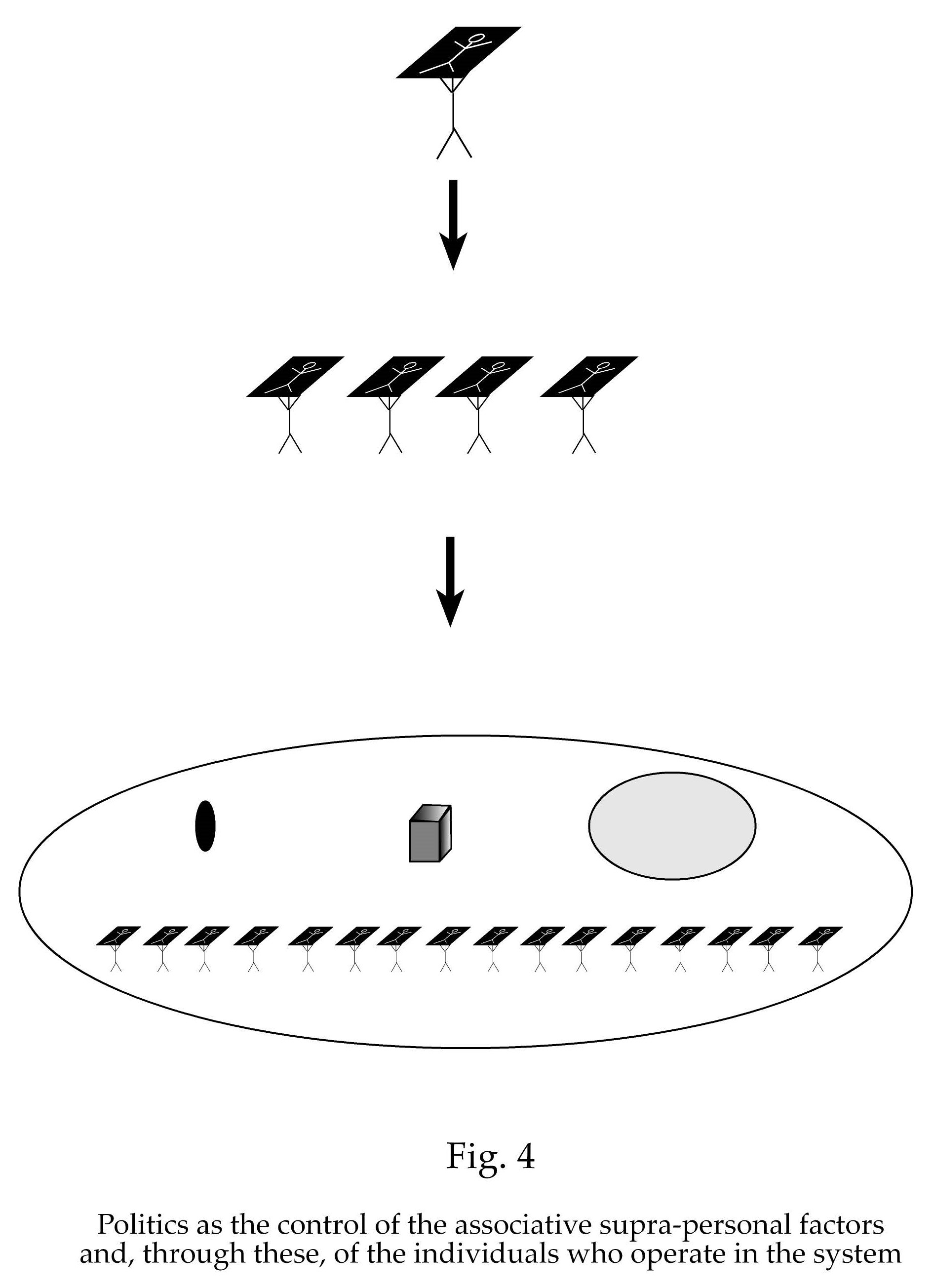

5.16 The Consolidation of Politics

On the etymological level, the terms “urbanism” (from the Latin urbs) and “politics” (from the Greek πόλις; cf. 6.2) are equivalent, having both the common meanining of “city”. Also the etymological sense of the word “government” (referring to the helm, and thus implying directionality, for which see above) is significant; “within the city, thus understood as a political structure, that process of the centralization of power in a single central axle that controls all the para-perceptual and supra-personal factors that had been developed in the late prehistoric period came to its full maturation during the urban revolution. Therefore, we can define politics, for our purposes, as centralized systems of control applied to supra-personal tensional factors, a system that unifies the social complex and proposes a finality for it. The control of the supra-personal factor entails control of the individuals who are involved, and from this, the exponential force of the new political power is derived” (Buccellati, Origins, p. 69).

This process and this dynamics can be summarized in the following charts:

All in all, the historical innovation of this time was the concept of hierarchy (for which cf. above; cf. also Section 3.8).

Back to top: Part II Section 5

5.17 Primary Perception

Para-perception, leading to the formation of secondary perceptions, had an important role in the urban revolution (cf. Section 3.8) but this does not mean that primary perception was lost.

Primary perception is “the internal appropriation on the part of the knowing subject (the person) of external facts, attributing to them a particular sense or meaning” (Buccellati, Origins, p. 73); secondary perception “consists in collecting the primary perceptions in an intuitive way which is not necessarily identical with a more theoretical process of reflection” (Buccellati, Origins, p. 73); the latter is a “para-perception”, since it is no longer tied to a single perceptual moment (see the example of the seed in Section 1.3), without necessarily reaching an abstract conception (cf. Section 3.6).

Five observation can be presented, showing how primary perceptions are still active:

- a primary perception of the secondary perception: “every member of these new urban (and state) groups could be seen as members of a real group, even if this group was no longer a direct object of perception, as was the case in the prehistoric community based on face-to-face relationships. This is explained with the familiar metaphor applied to the ‘citizens’ of a given urban settlement: that is, with the term ‘sons of GN’ where GN stands for the proper geographical name of the city” (Buccellati, Origins, p. 73);

- a stress on the private dimension: the dichotomy between public and private (already existing in prehistoric time, cf. Chapters 2.2-2.3) reached in this period its climax: “the primary perception of personal relationships became much more significant and important just because it was opposed, in its diversity, to the para-perceptual whole it was immersed in” (Buccellati, Origins, p. 74);

- the relationship with the absoluteNote 4: religion (cf. Buccellati 2024 When along with the companion website Mes-Rel) became much more of a complex system and “primary perception emerges as the need for harmony with the world, and religion, just like the social system, offers mechanisms so that the individual can channel this base perception in the right way” (Buccellati, Origins, p. 74);

- an alternative to political grouping: “the persistence of values associated with primary perception led to the introduction of an alternative model of social and political structure: the tribe” (Buccellati, Origins, p. 74; cf. Section 16.6); the tribe emerges as a state parallel to the territorial one, with criteria which are more related to primary perception;

- the persistence of impact as an elementary experience: “primary perception still retains a profound force as the criterion for the evaluation of everything that is built on the social framework based on secondary perception. This is what is called ‘elementary experience,’ a driving force that still serves as a guide to define property and the limits of the great social systems” (Buccellati, Origins, p. 74).

Back to top: Part II Section 5

5.18 The Primary Nuclei

The sense of primary, elementary experience can be envisaged in two specific concepts, i.e. those of the neighborhood and the hearth, the latter being definible by the English word “household”, in Sumerian é, equivalent to the Akkadian bītum, referring to both the “house” and “family” (a concept attested also in the Hurrian culture and in the Mycenaean one, specifically in the word μέγαρον).

The very concept of “house” will be, in later times, applied also to define political entities (see, specifically, in the Iron Age, the development of states named after specific anthroponyms), with a peculiar tradition and pantheon (cf. Section 6.7).

More in details, the concept of neighborhood is expressed by the Akkadian term babtum (with its Sumerian equivalent dag.gi4.a), meaning “a whole of doors”, i.e. doors which open onto a common open space, and therefore a district (see on this topic the related Monograph; for “peripheral districts”, cf. Section 6.2, with Note 2).

This “topological” structure also had a social by-product: in many Akkadian texts, we can, in fact, find the expression “sons of a district” (mārū babtim), that indicates the internal solidarity of the population of a neighborhood. Districts were probably identified with a group of houses with a specific focal point, a temple or a gate of the city.

At the center of many cities there was the temple of the patron god around which the population ideally congregated (cf. Section 6.7); the center of the districts could be instead a smaller temple or a chapel.

Neighborhood also had a juridical role we can see in two aspects:

- each quarter had its own rabiān babtim, the “great of the district”, a kind of “mayor”;

- the rabiānum appears as a legal person in situations of conflicts.

Back to top: Part II Section 5

5.19 Chronology and Periodization

Cf. also the chronological chart at the end of the volume.

Since we are dealing with broken traditionsNote 5, to re-frame events in a chronological sequence we have to rely at first on archaeological evidence.

Some few remarks must be addressed:

- terminology: some terms and labels for specific periods are liguistically connotated, and cannot be easily translated or applied to other languages (e.g., the American nomenclature is based on excavations in the Diyala region, cf. Section 6.11.1, while other European languages adopted different labels for the same historical period);

- the archaeological evidence of the urban revolution period is characterized by:

- monumental architecture;

- abundance of luxory objects;

- very specific ceramic types.

- epigraphic evidence begins in this period, with the most archaic text (dating from 3200 BC) coming from Uruk (Section 6.10) and Susa (Section 7.6) and they are of administrative and school character; the first true prose tests have instead a political character, such as the royal inscriptions, the earliest attested at Kish around 2700 BC (cf. Section 6.10.3); the first and greatest archive of the third millennium BC is that of Ebla (cf. Section 6.11.4). Last, Sumerian texts were considered fundamental for the school and scribal tradition and thus continued to be copied through the centuries.

Back to top: Part II Section 5

Notes

- Note 1: for the concept of “built environment”, see the Grammar (particularly Section 1.22) of the Urkesh website. Back to text

- Note 2: on this topic, specifically in the Kassite Babylon, see the importance and (even artistic) role and relevance of the kudurru stones, monumental documents of land donations previously (wrongly, since they were found in secondary deposition) retained as land markers and currently re-defined as land-donation documents usually preserved in the temple, where many of them have been recently found in situ (see, about these artifacts, e.g. Gelb Steinkeller Whiting 1991 Ancient Kudurrus). Back to text

- Note 3: for an example of seals and sealings, see the Urkesh website. Back to text

- Note 4: on the concept of “absolute”, see the related monograph in Mes-Rel. Back to text

- Note 5: for the notion of “broken tradition”, see the dedicated theme in CAR. Back to text

Back to top: Part II Section 5