Back to top: Part II Chapter 7

7.1 The Alternative Model

The hypothesis describing the nuclear territorial state implied two factors:

- the geographical layout, conditioning the social group;

- the historical information we have for the middle/end of the third millennium BC.

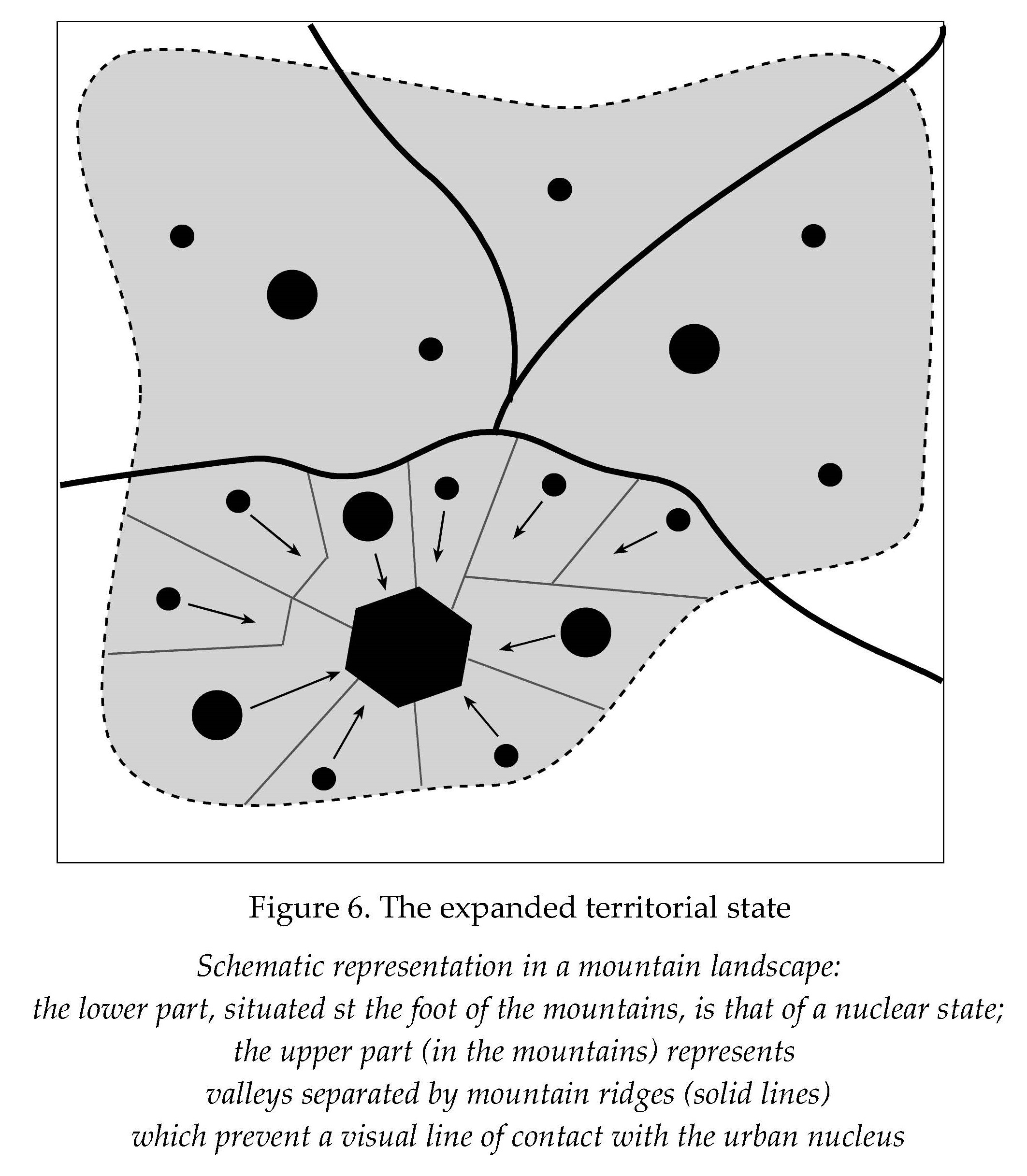

What changed with the expanded territorial state was, above all, a different perception of the territory which “altered the requirements of solidarity and thus affected the very nature of the state” (Buccellati, Origins, p. 97; cf. Chapter 6.2).

The organization of space remained basically that of the nuclear territorial state, but the distance from the city center became that long that the visual contact was impossible; this is graphically represented in Figure 6.

The main consequences affecting the political structure of society were:

- the solidarity of the social group was based on factors that go beyond territorial contiguity;

- an effective aggregation could overcome the limits given by the lack of territorial contiguity; but it was because there was an associative driving force that went beyond the territory as a social glue for the various groups.

Back to top: Part II Chapter 7

7.2 The Geographical Context

The state-city remained the central hub even in the expanded territorial state, which is still, in a way, a nuclear territorial state, since it is still centralized in a single urban settlement.

The very difference was in the different perception of the expanded territory which made the mutual relationships more complicated, since the individuals faced more difficulties in knowing the whole territory personally; all this ended in a new configuration, defined by two features:

- the conditions of the terrain created more barriers to individual communication;

- the dimensions and the density of settlements were reduced; they are small and isolated villages.

This configuration is typical of mountainous landscapes, like the wide arc encompassing the land from the North-West to the South-East, the Zagros and the Caucasus, the Pontic and the Toros mountains (cf. below, 7.8). Such a configuration implies two important elements:

- the territory constitutes a real homogenous surrounding to the urban nucleus;

- the solidarity of the villages with one another and with the urban center is only based on limited geographical and territorial elements (and the city looses its centrality).

The city, as the central reference point, is defined as such by the villages which pre-existed it.

Another possible configuration of the expanded territorial states is that of the steppeNote 1 (cf. below 7.7), where the distances are greater and the resources are few (especially water). But the most important feature is that there are no villages in the steppe which is, in the end, an alternative model to the expanded territorial state.

Back to top: Part II Chapter 7

7.3 State and People

In the case of the expanded territorial states, and peculiarly that of the mountainous landscape, the principle of solidarity (the factor of cohesion of the social group) precedes and thus transcends territorial limits.

About awareness and identity, “As long as there was no city, the “expanded” population did not have a clear awareness of its own supra-local identity (that is, beyond the village). It is when the city came into existence that this awareness fully emerged” (Buccellati, Origins, p. 99.

The population of the expanded territorial states located in the steppe offers a different structure: in fact, there are no villages at all in the steppe; here, it was the people creating the territory, in a way “inventing the steppe”, for sure in the second millennium BC but very likely already in the second part of the third (see Buccellati 1993 Amorrei; cf. Chapters 7.7, 8.1, and 11).

Back to top: Part II Chapter 7

7.4 The Mythic Idealization

There is a specific myth which can tell us something relevant to the topic of politics in the third millennium BC: it is the Hurrian Myth of “Silver”Note 2, personified metal, known to us thanks to a Hittite late copy, which involves the god Kumarbi, patron god of the city of Urkesh/Tell Mozan (because of the setting of the story in this city we can absume that its historical background must be retrace in the third millennium BC).

In the first section of the myth, the proemium, “we can read the myth as the description of the villages found in the mountain region which were in conflict, partly due to the rivalry deriving from the special status of who controls a precious metal like silver. It is a general sense of dependence on a higher level of integration which is, however, latent (the topos of the unknown father)” (Buccellati, Origins, p. 100.

In the second section of the myth “in the euhemeristic interpretation I would like to apply to the text, the city is discovered as the source of authority that brings both justice and defense against human enemies and natural dangers” (Buccellati, Origins, p. 101.

Furthermore, two points can be stressed:

- the topos of the unknown father suggests a sense of supra-territorial identity, something that we can consider in terms of ethnic solidarity;

- there are cosmic and urban realities which add the presence of a “civil consortium”

In the third section of the myth Silver goes up to the mountains looking for his father Kumarbi who is not there; here “we see a description of the reciprocal relationship between the villages in the mountains and the city in the plains. The distance remains and there is no visual contact. The perception of the city is filtered in a way that makes the relationship nuanced and almost elusive, but the substance of the necessity to integrate is affirmed” (Buccellati, Origins, p. 101.

All in all, “in the situation described in the myth of Silver, instead, the villages maintain their distance and pre-urban identity: the tie with the city can almost be ignored, and it requires specific effort to discover it [but] the recoprocal effort can still be frustrated because of the geographical and environmental situation. It is this expanded cohesion that I see as an alternative to the nuclear state – almost always a city-state (the city remains the hub of power) but a state whose internal ramifications are much more pervasive and complex (8.1)” (Buccellati, Origins, p. 101).

Back to top: Part II Chapter 7

7.5 The Historical Reality

The existence of expanded territorial states at the end of the third millennium BC and the beginning of the second millennium BC is well documented; another evidence of this is a particular type of royal title, which represents a real statement of political awareness (a detail which will be further investigated in Chapter 10.4 dealing with Naram-Sin).

The title unites the name of a territory or an ethic identity related to a territory to that of a city: the most famous is “King of Mari (cf. 6.11.2) and Khana” (cf. below), appearing in the 19th century BC. Even earlier (end of the third millennium BC), a similar title was attested: “King of Urkesh (cf. below) and “Nawar”, being the latter a wider territorial reality.

Back to top: Part II Chapter 7

7.6 The Foothill Region

Back to top: Part II Chapter 7

7.6.1 Urkesh

Cf. the dedicated website (Urkesh); for bibliographical references, see the “Urkesh electronic Library”.

The site of Urkesh/Tell Mozan is located ca. 10 km to the South of the Tur-Abdin mountain chain, in northern Syria. As already seen above, the site is strongly connected to a Hurrian mythological milieu, suggesting a relationship between the city and the mountains. The region of Urkesh, which could be identified with the aformentioned “Nawar” which appears in a royal title (from Atal-Shen) datable to the end of the third millennium BC.

At the top of the mound is located the Temple BA, placed on a very high Temple Terrace (BT); this temple dates to ca. 2500 BC but immediately beneath it there is a corner of a temple, still unexcavated, dating ca. 3400 BC (see Buccellati F 2010 Terrace; cf. Kelly Buccellati 2015 Power; cf. also Head 2023 Anthropocene)Note 3. Two inferences can be advanced:

- that the temple of the third millennium BC was dedicated to the god Kumarbi and that his cult was Hurrian;

- that the temple of the fourth millennium BC would had a similar function (on this very topic, see e.g. Buccellati Kelly Buccellati 2005 Hurrian and Kelly Buccellati 2016 Hurrian).

The importance of mountains was very relevant for the population of Urkesh; this is evident in the aformentioned “Myth of ‘Silver’” and also by other archeological elements (see on this topic Buccellati 2009 Logogram with the discussion on an interesting “architectural logogram”).

From ca. 2300 BC we have solide evidence for the Hurrian ethnicity of the people of Urkesh: even though, it is possible, for archaeological, textual, and environmental data (see e.g. Buccellati Kelly Buccellati 1997 Ethnicity) to backdate this evidence also to the previous millennia, in the period when Urkesh formed a model of expanded state opposed to the nuclear states of southern Mesopotamia.

Back to top: Part II Chapter 7

7.6.2 Susa

Elam is a proviledge territory located, accordind to the inscriptions of the kings of Akkad, to the East of Sumer. The royal title for the ruler of this country was “King of Elam” (without mentioning a specific city, even if the expression “the cities of Elam” is attested). In this section the core is Susa, while in Chapter 7.8 the focus is on Anshan.

The urban status os Susa, modern Shush, dates back to the fourth millennium BC even if the largest information comes from tablets contemporaneous to those of Uruk (cf. 6.10.1); these tablets attest a language different from Sumerian, called Proto-Elamite, a language which (as Hurrian at Urkesh) contributed in shaping an ethnic reality with a sense of social and political identity different from that of the nuclear territorial states (cf. Chapter 6) and closer to that of the expanded territorial states.

Back to top: Part II Chapter 7

7.6.3 Subartu and Elam

Subir (Sumerian) and Subartu (Akkadian) are terms referring to the North in general, particularly to the North-West of Syro-Mesopotamia (the Sumerian/Akkadian origin of these toponyms is disputed); at the same time, the terms Elam/Elamtu are attested as referring to the region at the foothills to the East of Sumer (the toponyms reflect the original Elamite Haltamtu).

While Subir is not applied as a territory with a specific political identity, Subartu in found in an inscription of Naram-Sin in the expression “governors of Subartu”: therefore, Subartu was a political entity (see Michalowski 1999 Sumer Dreams). Even though, the title “King of Elam” appears several times in inscriptions of the kings of Akkad; the singular “king” could reflect the fact that the toponym “Elam” actually represented not just a geographical but rather a political entity (sometimes it is also spoken of an Elamite “federation” but without any clarity in this sense in the archaeological or textual evidence).

Semantically, in the North of Syro-Mesopotamia the name of the cities often used exclusively (“King of Mari”) or, where the name of the region also appears, it comes after the name of the city (“king of Mari and Khana”).

Back to top: Part II Chapter 7

7.7 The Steppe

For bibliographical references on this topic, cf. note 1.

In the case of the steppe (diffently from that of the foothills), the incorporation of the land beyond the fluvial plain can in fact be dated to the second half of the third millennium. This is why we can speak of “invention of the steppe” (cf. Chapter 11) “in the specific sense that this landscape started to become part of the geopolitical reality of Mesopotamia only long after the formation of the territorial states” (Buccellati, Origins, p. 104).

The desertic territory has been for sure frequented already in the Paleolithic but the sites there remained isolated, limited to a few springs of fresh water, the oases. This is the reason becase of Mari (cf. Chapter 6.11.2) remained anchored to the formula of the nuclear territorial state and is not placed in the Sumerian King List.

Back to top: Part II Chapter 7

7.8 The Mountain Crescent

The central Syro-Mesopotamian plain was kind of embraced (to the North and to the East) by the mountain arc including the Antitaurus and the Zagros. Human and natural resources in the mountain regions were numerous (cf. above the “Myth of Silver”), and the landscape had been profoundly assimilated into common perception since remote times.

“The states in the foothills 7.6 located on the edge of the plain were the ones that related to the mountain reality most easily, serving as a hinge between the plains and the innermost parts of the highlands. Here, cities and therefore proto-states were found, although in a very limited way, dating back to the beginning of the processes we are analyzing, to the fourth millennium.

Back to top: Part II Chapter 7

The West

In the western part of the wide mountain crescent, we find the site of Arslantepe (today in modern Turkey)Note 4, known in the second and first millennium BC as Malatya/Malitiya/Malizi; the site, defined as a case of a centralized but non-urbanized society, had a great structure that could be considered the most ancient example of a palace yet excavated, and, in connection with this, a system of administrative recording based on a very systematic use of sealings on cretulae.

Back to top: Part II Chapter 7

The East

On the other edge, in the northern part of the Zagros, we find the site of Tepe Gawra, important for both its stratigraphic sequence and also for its monumental and domestic architecture showing a strong local character. Here, “the arrangement of building spaces and the nature of the discoveries suggests the presence of a “chief” tied more to the mountain traditions than to those of the plains” (Buccellati, Origins, p. 106).

In the Southern part of the Zagros, Anshan (modern Tall-e Malyan), is closely connected to Susa and the proto-Elamite traditions; “it is possible that the urban center of Anshan was near the territory of Awan, considering the distribution of the use of the title “King of Awan” and “King of Anshan” […]. What should be emphasized in our context is the vastness of the territory (see also the next section, 7.9 to which these definitions refer: certainly the state structure in the mountain regions had a very different character from that of the “expanded” territorial states” (Buccellati, Origins, p. 106).

Back to top: Part II Chapter 7

7.9 On the Far Edges

The phenomenon of the spread of territorial states insisted, between the end of the fourth and the middle of the third millennium BC, on a very wide area; approximately, from the Mediterranean coast (Byblos and MersinNote 5) to the West; to the Kura-Araxes valley, the Dagestan plain, and the Caucasus to the North; to Tepe Yahya, Shahre Sohta, Jiroft, and, ultimately Anshan to the East (not to forget the Indus river valley); to many settlements nearby the Gulf, to the South.

Even the vastness of this area, “the ideological landscapes of the Mesopotamian culture (cf. 8.6.3) refer to these remote localities but are somehow present in the geographic perception. Given the geographical entity of such a wide area, the cities of the highlands were substantially isolated in a rarefied urban landscape which only consisted of villages of medium and large size (cf. 8.6.2).

Even though, it is clear that the very nature of the settlements involved a social cohesion on a level that was unthinkable in the relatively recent periods of prehistory.

On another level, that of “scribalcy” (cf. Chapter 5.4), the lack of written texts as shown in some excavations (and the uncertainty about the graphic symbols in the Indus River valley) is presumably not just due to chance, but could reflect a real lack of the scribal system in some centers distant from the very core of the state formation diffusion.

About this phenomenon a remark must be addressed:

“Given the importance I have attributed to writing as the apical moment of the development of supra-personal structures which led to the formation of the state (Chapter 4), we must ask how is it that there are nevertheless urban and presumably state structures even without the use of writing. The response may be found in an extension of the concept of para-scribal culture (4.7), a concept that I would like to call 'homoio-scribal' ('similar to the product of a scribe') or more succinctly 'homo-scribal' ('identical to the product of a scribe'). By this I mean to emphasize the social-cultural conditions concentrated in writing more than writing as a mechanism. [...] The foundational social-cultural conditions therefore consisted of the development of an entire para-perceptual system, of which scripture was the apex, but not exclusively so. These other modalities, even if less efficient and productive, somehow served a similar goal, to reify words and thought” (Buccellati, Origins, p. 107).

Nonetheless, given the importance of writing in the formation of the first state-cities, it is unavoidable to see the “cradle” of this phenomenon in ancien Sumer.

Back to top: Part II Chapter 7

Notes

- Note 1: on this topic, see e.g. Buccellati 1993 Amorrei and Geyer 2001 Conquete (reviewed in Buccellati 2003 Geyer). Back to text

- Note 2: it is more specifically the text CTH (Catalogue des textes hittites/Catalog der Texte der Hethiter) 364, found in the Hittite capital Ḫattuša/Boğazkale, also known as “Der Gesang/Das Lied vom Silber” (“The Song of Silver”), for which see the “Hethitologie Portal Mainz” [H P M] (“Mythen der Hethiter”); for an English translation of the text, see e.g. Hoffner 1998 Myths, pp. 48-50 [text no. 16] (see excerpt). Back to text

- Note 3: for a complete and updated bibliography about the Temple Terrace, refer to the “Urkesh electronic Library” at this link. Back to text

- Note 4: on this site, see e.g. the mission website (Arslantepe); for monumental architecture, see (on the Hittite Monuments website), the dedicated section; for Arslantepe in the fourth millennium BC, see Frangipane 2010 Economic; for the many cretulae and sealing found at Arslantepe, see Frangipane 2007 Cretulae. Back to text

- Note 5: in the Mersin area, it would be worth mentioning, the site of Mersin-Yumuktepe, for which see Caneva 2004 Yumuktepe and Caneva 2010 Yumuktepe. Back to text

Back to top: Part II Chapter 7