Model Cities and City Models:

Urban Conception in Ancient Near East and Egypt

PDF version downloadable at this link.

Encyclopædia Britannica, lemma 'City'

Back to top: Birth and Development of Cities

Abstract

This monograph aims at sketching out, very cursively, the development of the idea (and especially the structure) of city in Egypt and in Ancient Near East, in a period between the so-called “urban revolution” (ca. mid-fourth mill. BC) and the Iron Age I-II (ca. 12th-7th cent. BC): a journey from the Mesopotamian Uruk (“the first city”) to the Palestinian fortified cities, such as Beersheba. The present paper is also an attempt to understand, through the analysis of archaeological, artistic and written sources, if a unique and shared idea of city has ever existed or if, rather, different city models were conceived according to different mindsets, trying to identify similarities and differences with Greco-Roman and modern cities. Examples of cities taken from different geographical areas (Egypt, Anatolia, Syrian-Palestinian area, and Mesopotamia) will be presented, with a look also at pre-citizen or para-citizen experiences such as village communities (e.g., Çatal Höyük, the Egyptian workers’ villages of Deir el-Medina and El-Amarna) with a comparison, in negative, with nomadic realities retaining a different concept of community and, consequently, displaying different housing models. I will try to underline how each settlement or city has its very roots in the social, political, and religious mentality and conception of the men and women who thought, planned, and lived therein: it is not possible to understand a city structure without a deep analysis of the culture that produced it. This journey into the past allows us to build bridges with the contemporary and, starting from ancient experiences, to ask ourselves questions about our present and our concept of city, discovering how וְאֵ֥ין כָּל־חָדָ֖שׁ תַּ֥חַת הַשָּֽׁמֶשׁ, nihil sub sole novum (Ec. 1:9).

“Se ti dico che la città cui tende il mio viaggio è discontinua nello spazio e nel tempo, ora più rada ora più densa, tu non devi credere che si possa smettere di cercarla”.

(Calvino, Italo 2010, Le città invisibili, Milano, p. 163).

וְאֵ֥ין כָּל־חָדָ֖שׁ תַּ֥חַת הַשָּֽׁמֶשׁ, nihil sub sole novum (Ec. 1:9).

Back to top: Birth and Development of Cities

Introduction

This paper aims at retracing, in a bird’s-eye view, the development of city structure in Egypt and Ancient Near East, analysing some of its peculiar characteristics, both with regard to its urbanistic form and ideological conception, trying to understand whether an unique model of city or, rather, a plurality of experiences can be traced. Given the complexity of the problem (both diachronic and diatopic in its vastness), I will limit myself to provide just a few reflections, since this is a subject which, as Mario Liverani well pointed out in his latest volume on the subject, requires a multifaceted study embracing a great deal of knowledge (Liverani 2014 History: vi). I will develop the paper in a chronological way, starting from Neolithic Anatolia and Mesopotamian first cities (on Mesopotamian city, see e.g. Van De Mieroop 1997 City) in the 4th mill. BC, moving then to Egyptian cities (from the Pre/proto-dynastic period to the New Kingdom), later coming back to Third/Second-millennium Near East, roaming from Anatolia to Syria and Assyria, finally reaching Babylon and eventually wandering around Iron Age II-Palestine, where a new conception of city and consequently a new town planning seems to emerge.

Back to top: Birth and Development of Cities

Starting from Ancient Near East

Back to top: Birth and Development of Cities

Neolithic Anatolia

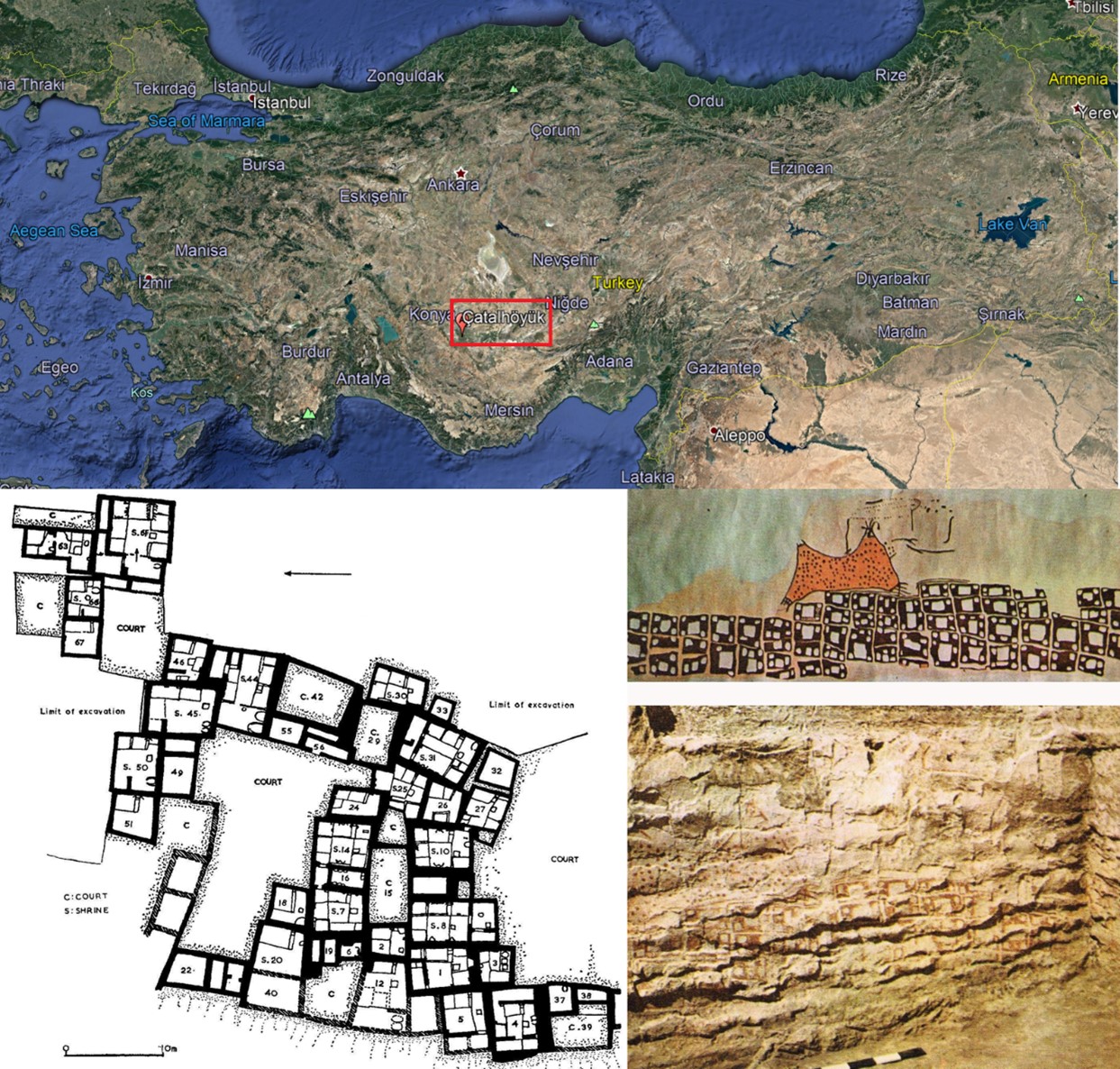

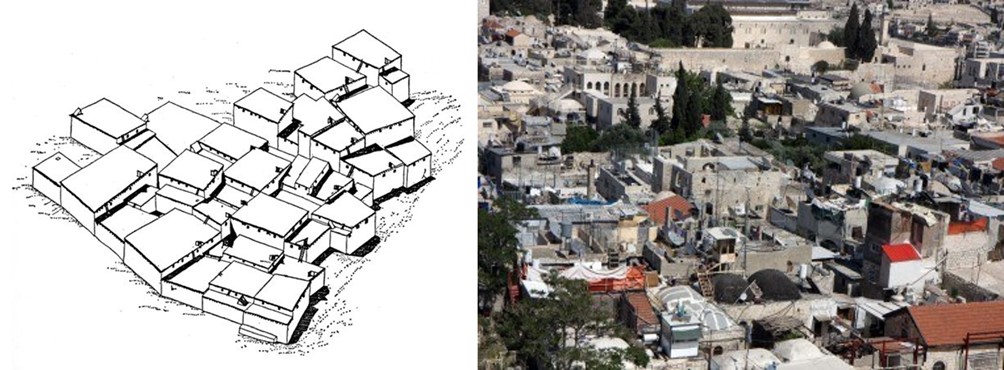

Our journey starts before the dawn of the city, in a phase definable as “the ‘city’ before the city”: the village. We are in Turkey, ancient Anatolia, in the settlement of Çatal Höyük (Turkish term meaning “fork mound”), in the plain of Konya (Figure 1, top). The site, excavated during the twentieth century by James Mellaart and later by Ian Hodder, grew up during the Neolithic Ceramic Age (ca. 7000-4500 BC) and has eighteen stratigraphic layers (ca. 6500 and 5500 BC). It has an extension of ca. 600 × 350 m2 and presented a shape called “agglutinate”: there are no streets and the houses are placed one next to the other (Figure 1, bottom-left; Figure 2, left); this arrangement, created for defensive purposes at most, allows a circulation through the roofs of the houses that are used for different functions, a characteristic that is still evident today in the houses of the old city of Jerusalem (Figure 2, right). Among the various dwellings and their sanctuaries there are open spaces called “courtyards” which provided people with air, light, and space useful for the collection of household waste.

Anyhow, Çatal Höyük was not a city, as it lacks the political, religious, and productive structure that will be the result of what Vere Gordon Childe called the ‘urban revolution’ (Childe 1950 Urban). However, in one of the sanctuaries of level VII (ca. 6200 BC) there is a wall painting that provides useful information about the inhabitants’ conception of their village (Figure 1, bottom-right): it is a representation of the settlement and, above it, a figure interpreted as a volcano (perhaps the Hasan Dağ), or as a leopard: in any case, it seems to hold the meaning that the village is a place where protection from external natural elements is warranted, determining the survival of its dwellers.

Back to top: Birth and Development of Cities

Fourth-millennium Evolution

Between ca. 3500 and 3000 BC, in Southern Mesopotamia, traces of the aforementioned “urban revolution” can be recognised, with the birth of the first structured cities (with a precise architectural conception) and the State (a socio-economic concept); one of the most famous sites is indeed Uruk (Figure 3), which Mario Liverani labelled as “the first city” (Liverani 2006).

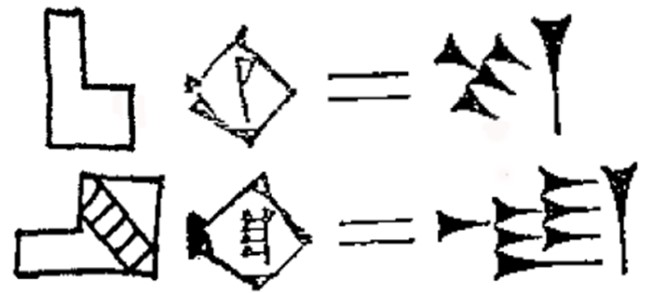

The Sumerian term for “city”, URU/IRI (Figure 4), is represented by a sign that in its pictographic phase seems to represent a strip or lot of land with at the centre, sometimes, a grid that could recall a street or perhaps a canal: Stephen Langdon brings the term back to the verb ER/ERI, “to give birth, to produce” (Langdon 1911 Sumerian: 213, 254). The main features of the city are the walls and the temple (Figure 5), as we read at the beginning of the Epic of Gilgamesh, the mythical king of Uruk: (Prologue, I 9-21) “He built the rampart of Uruk-the-Sheepfold, / of holy Eanna, the sacred storehouse. / See its wall like a strand of wool, / view its parapet that none could copy! / Take the stairway of a bygone era, / draw near to Eanna, seat of Ishtar the goddess, / that no later king could ever copy! / Climb Uruk’s wall and walk back and forth! / Survey its foundations, examine the brickwork! / Were its bricks not fired in an oven? / Did the Seven Sages not lay its foundations?” (George 2000 Gilgamesh: 1-2).

A confirmation of this first town structure can be found in the tablet reporting the “plan of Nippur”, dated ca. 1500 BC (Figure 6), nowadays on display in the Hilprecht collection at the Friederich-Schiller Universität in Jena; the sketch on the tablet shows the main elements of the city: a temple, the river Euphrates and various artificial canals, the walls with their gates, a moat and a park. The centre, not so much geographical as ideological, is, however, the temple of the polyad god Enlil “the lord of the wind”, called Ekur (“house of the mountain”), which bases its existence on the deity’s decision to reside in the city, as witnessed by a passage from a “Hymn to Enlil” (10-13; 109): “The mighty lord, the greatest in heaven and earth, the knowledgeable judge, the wise one of wide-ranging wisdom, has taken his seat in the Dur-an-ki, and made the Ki-ur, the great place, resplendent with majesty. He has taken up residence in Nibru, the lofty bond (?) between heaven and earth. […] Without the Great Mountain Enlil, no city would be built, no settlement would be founded”.

Back to top: Birth and Development of Cities

Moving to Egypt

Back to top: Birth and Development of Cities

Pre/proto-dynastic Egypt

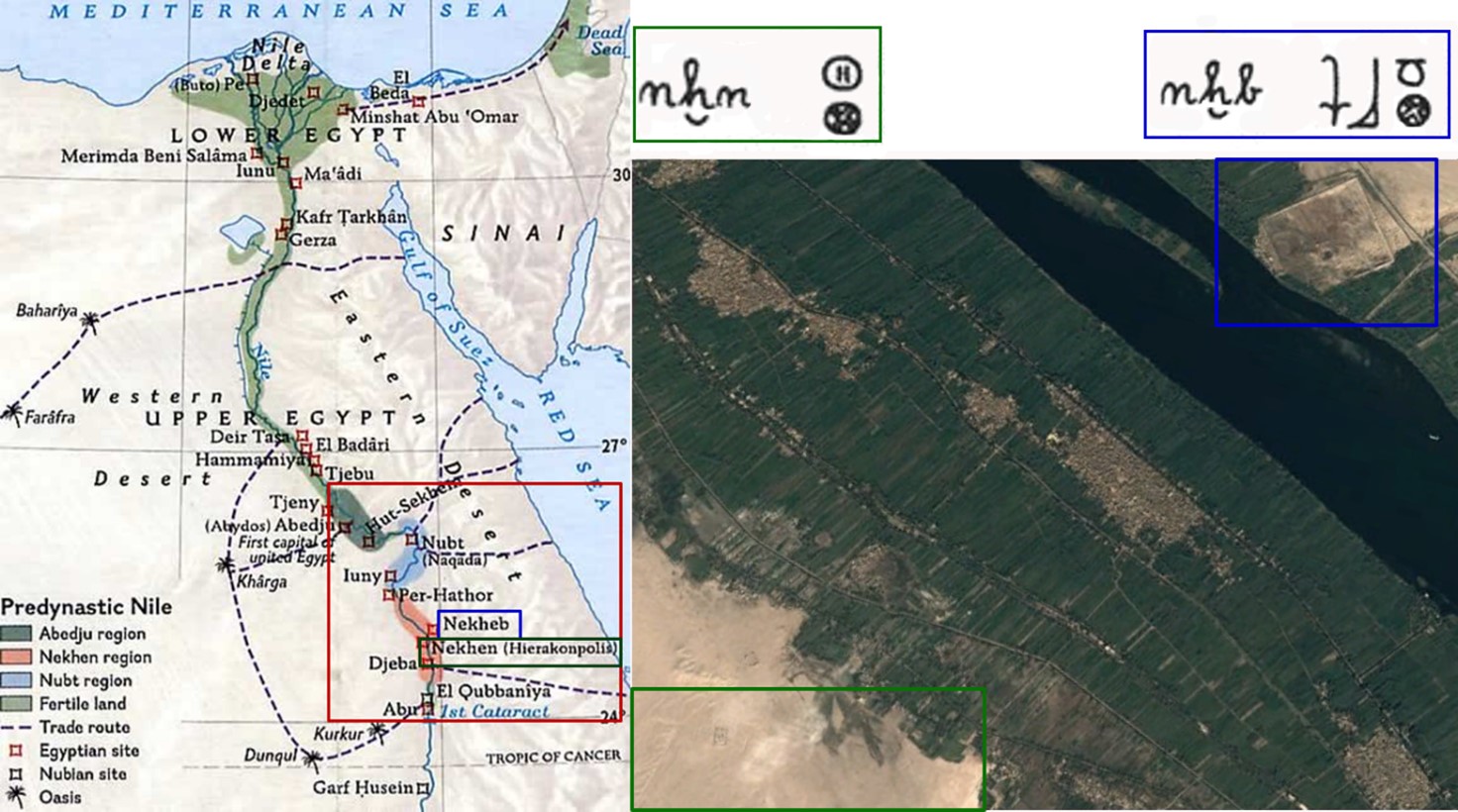

Meanwhile, in proto-dynastic Egypt (ca. 3200-3000 B.C.), there is archaeological evidence of the oldest structured cities, for example Nekheb (modern el-Kab) and Nekhen (the classical Hierakonpolis and today called Kom el-Ahmar), both in Upper Egypt (Figure 7).

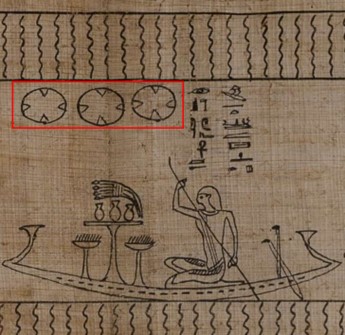

The Egyptian term for “city”, n(j)w.t, was determined by a sign, indicating the semantic scope of the word, represented by a circle with a crossing of streets (Figure 8). The term, which may also mean “village”, is already attested in the Old Kingdom (ca. 2700-2200 BC) in the “Pyramid Texts”, and finds a particular use in the New Kingdom (ca. 1540-1000 BC): in the text of the “Amduat”, 12th hour of the night, which tells of the resurrection of the Sun god at dawn, we find this passage prr jᶜr.wt=sn m rmn.w=sn m-ḫt spr nṯr pn ᶜɜ r n(j)w.t ṯn, “their [i.e., of the gods] uraei come out from their shoulders after this great god [i.e., the Sun] has reached this city”. Another example can be found in the Book of the Dead of Iuefankh, preserved at the Egyptian Museum of Turin, dated to Ptolemaic period (332-30 BC): in the vignette illustrating the formula 110, the determinative O49 is repeated three times (Figure 9): it indicates the place towards where the deceased navigates, i.e. the “Hotep Fields” (the “fields of peace”, otherwise also known as “the Fields of Yaru”), which are inserted with this determinative within the semantic sphere of the city: a sign therefore valid both in life and death.

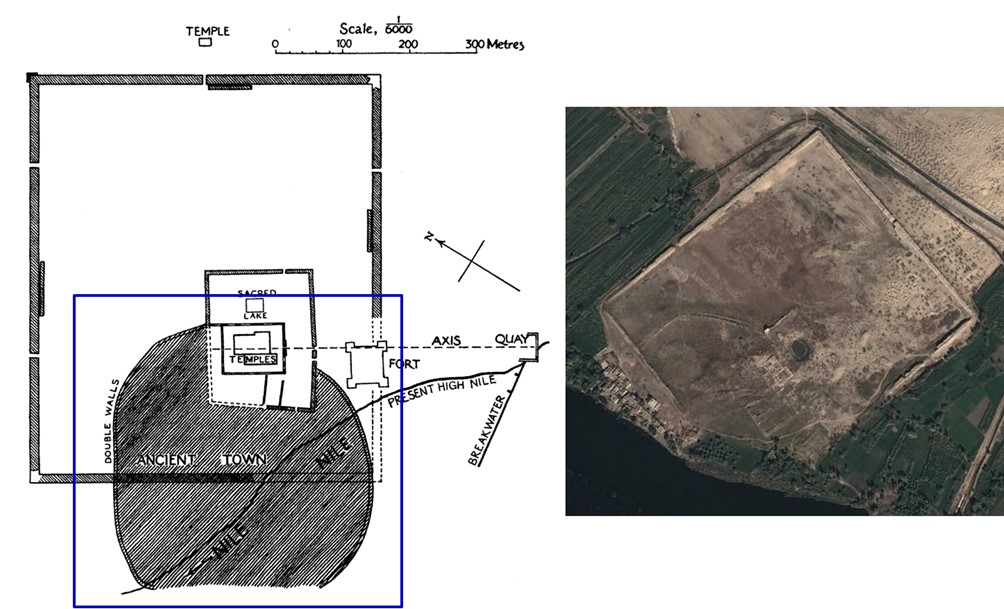

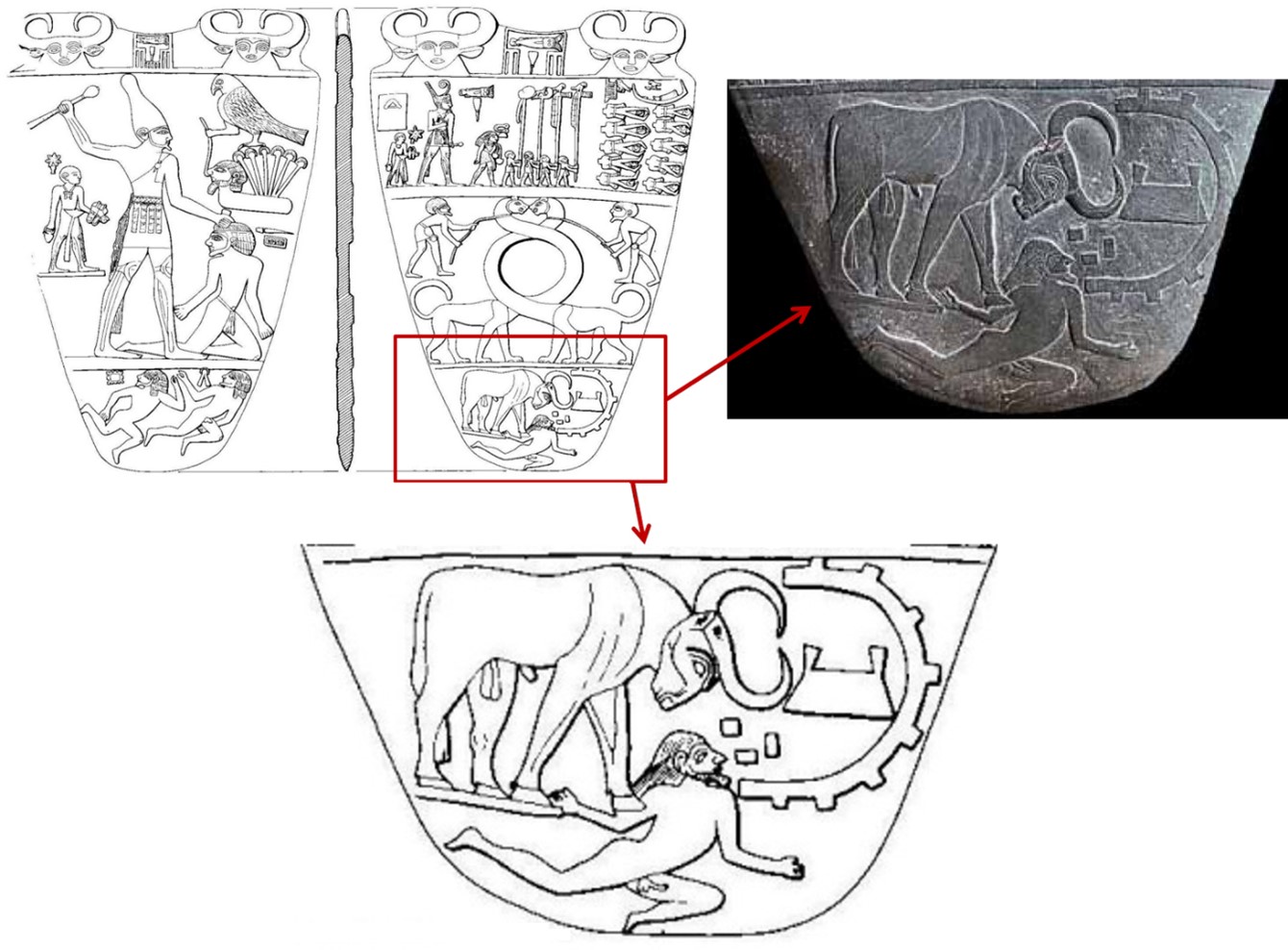

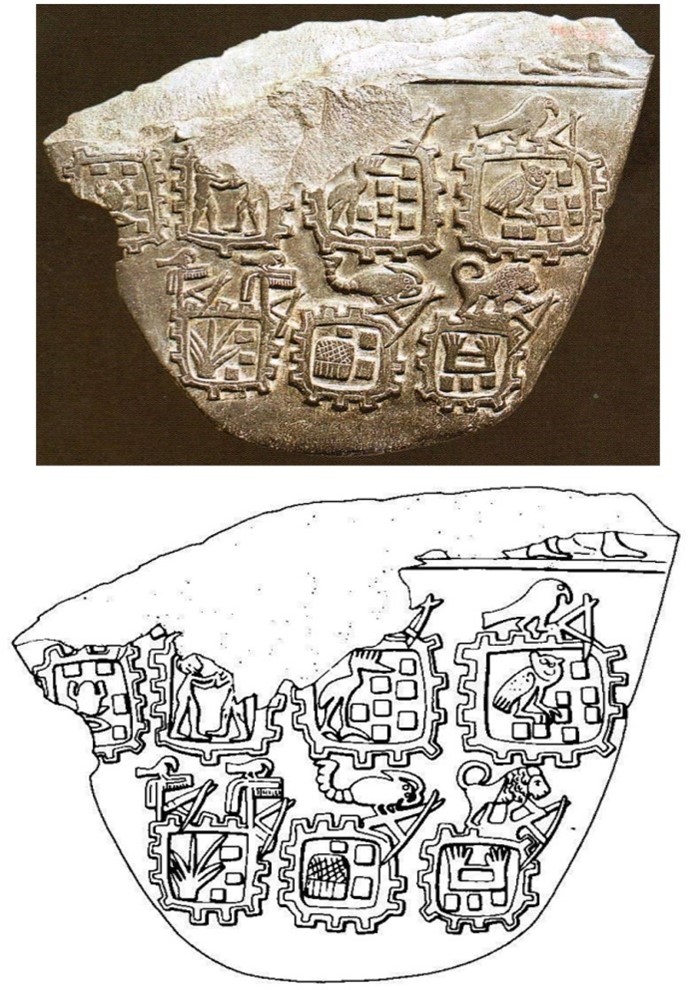

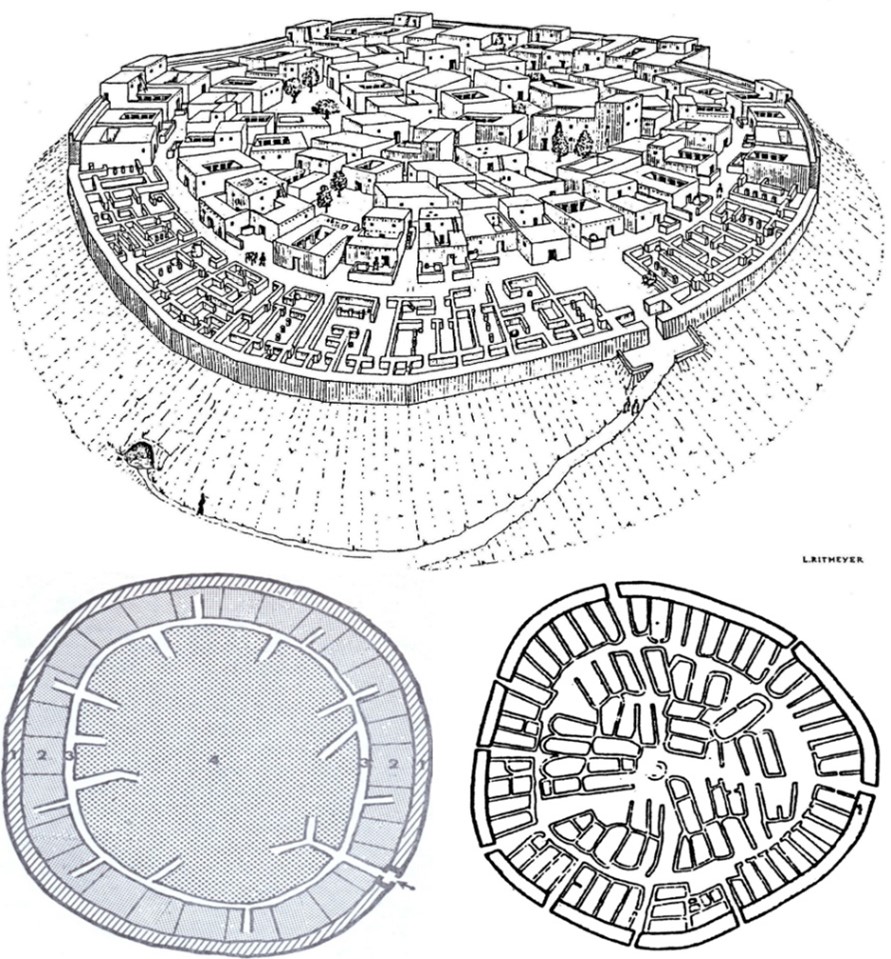

Returning to the cities of Nekheb and Nekhen: located respectively on the eastern and western banks of the Nile (Figure 7), they present an older, circular layout in the case of Nekheb, replaced by a more recent, quadrangular one, with mighty raw brick walls (Figure 10). The presence of these structures is also evidenced by two artefacts from Hierakonpolis, the “Narmer Palette” (Figure 11) and the “Construction/Destruction of Cities Palette”, also known as “Tjehenu Palette” (Figure 12): both dated to dynasty 0 (ca. 3150/3100 BC), they show cities with both circular and rectangular structure with thick walls with regular spurs or towers.

Back to top: Birth and Development of Cities

Old Kingdom

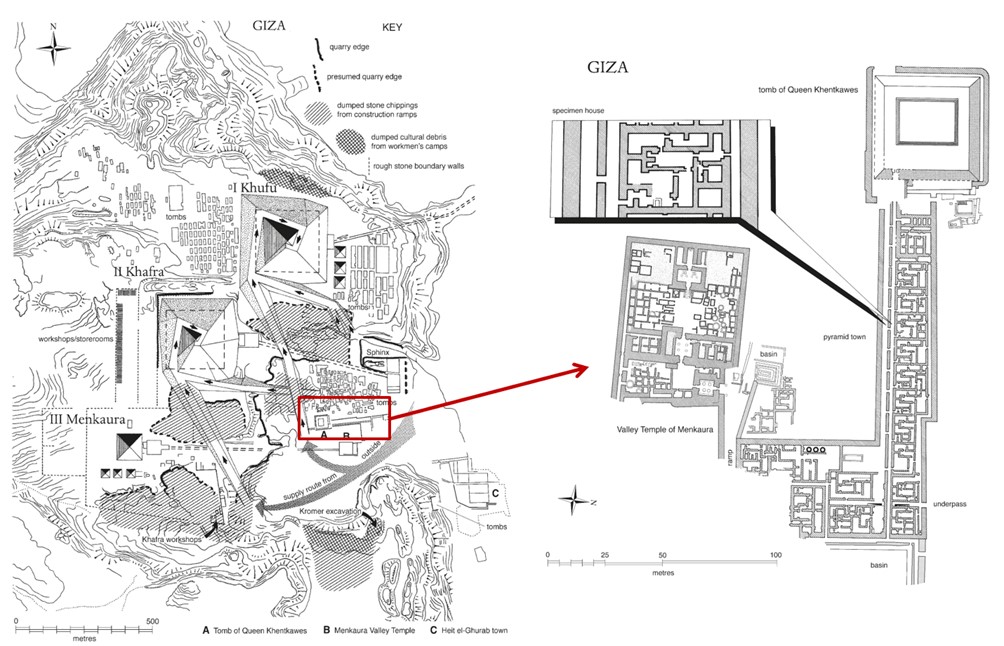

An interesting type of settlement is represented by the “cities of the pyramids” (Kemp 1998 Anatomy: 204-211 [20183]). The oldest preserved example is of the Old Kingdom (ca. 2700-2200 BC) in the plain of Giza, near the tomb of queen Khentkaues, who lived during the 4th dyn. (ca. 2613-2494 BC): a long series of dwellings for the priests in charge of the cult of the queen, with larger rooms for the collection of food (Figure 13).

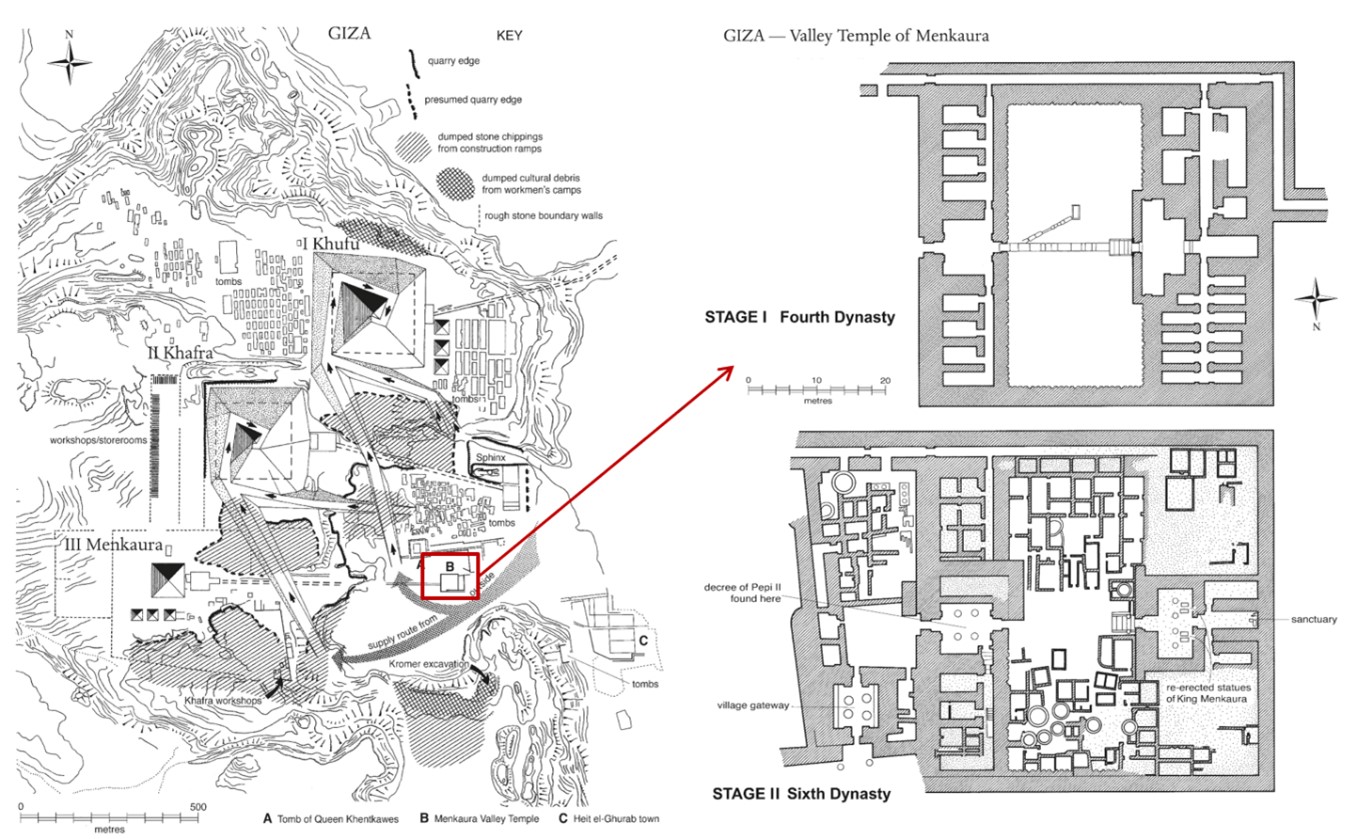

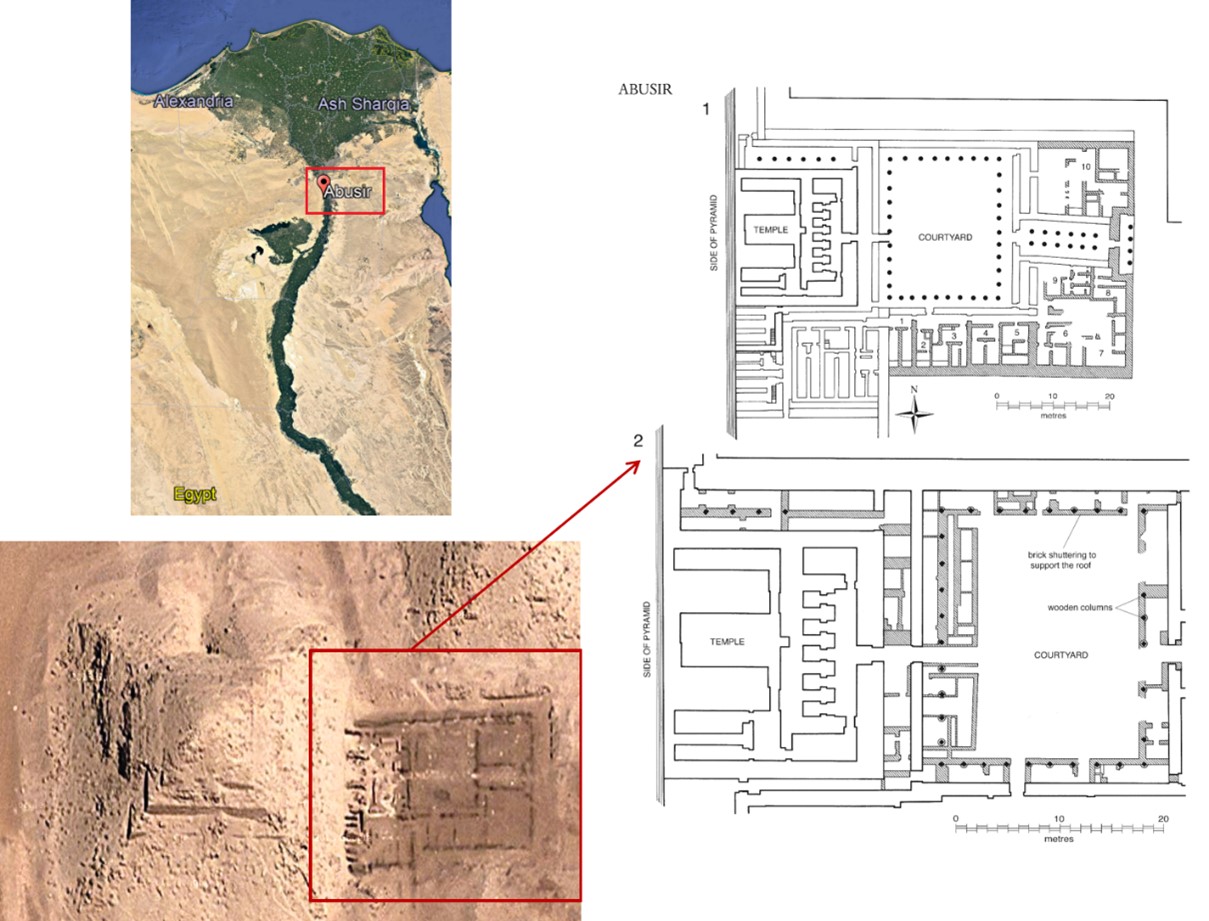

In other cases it could happen that, instead of building a new city, a previous building would be reused to set up houses and create a real settlement: the best documented cases are the temple in the valley of Menkaura, 4th dyn. (ca. 2613-2494 BC) at Giza (Figure 14), and that of the funerary temple of Neferirkara, 5th dyn., ca. 2494-2345 BC, at Abusir (Figure 15). The fragility of building materials, mud bricks and wood, does not allow to recover for the Old Kingdom (ca. 2700-2200 BC) other cities equally well preserved.

Back to top: Birth and Development of Cities

Middle Kingdom

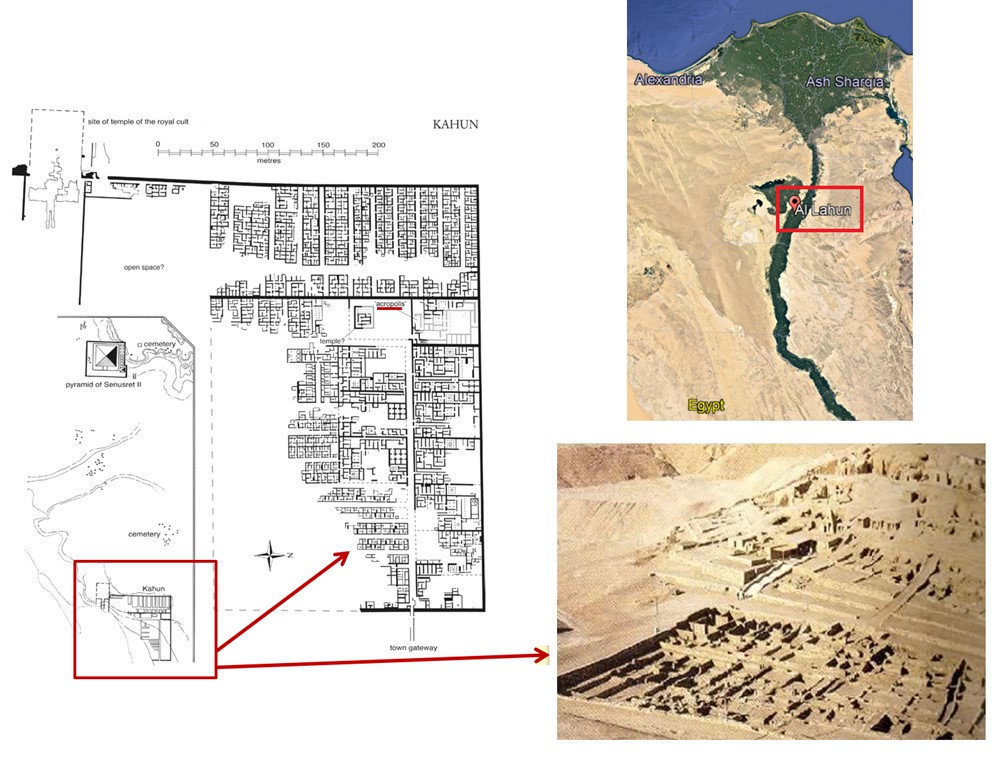

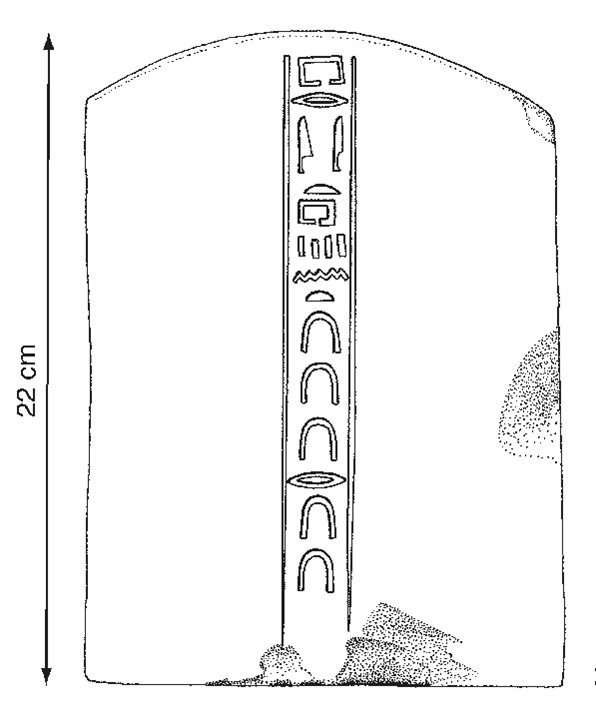

The situation improves with the Middle Kingdom (ca. 2000-1640 B.C) in particular with the case of Hetep-Senusret (“Senusret is in peace”, today Kahun), built by Senusret II during the 12th dyn., ca. 1991-1785 BC (Kemp 1998 Anatomy: 211-221 [20183]) (Figure 16): it is a “city of the pyramid”, but shows a more complex structure with a geometrically defined layout, divided into two parts, with a surveyed area (also from an altimetric point of view) usually defined (with anachronistic term) “acropolis”. Evidence confirming the design of Kahun’s urban layout is a limestone tablet used to mark the position of a group of houses, with an inscription that reads: pry.t 4 n.t 30 r 20, “one block, of four houses – 30 × 20 (cubits)” = ca. 15 × 10 m (Kemp 1998 Anatomy: 194-195 [20183]) (Figure 17).

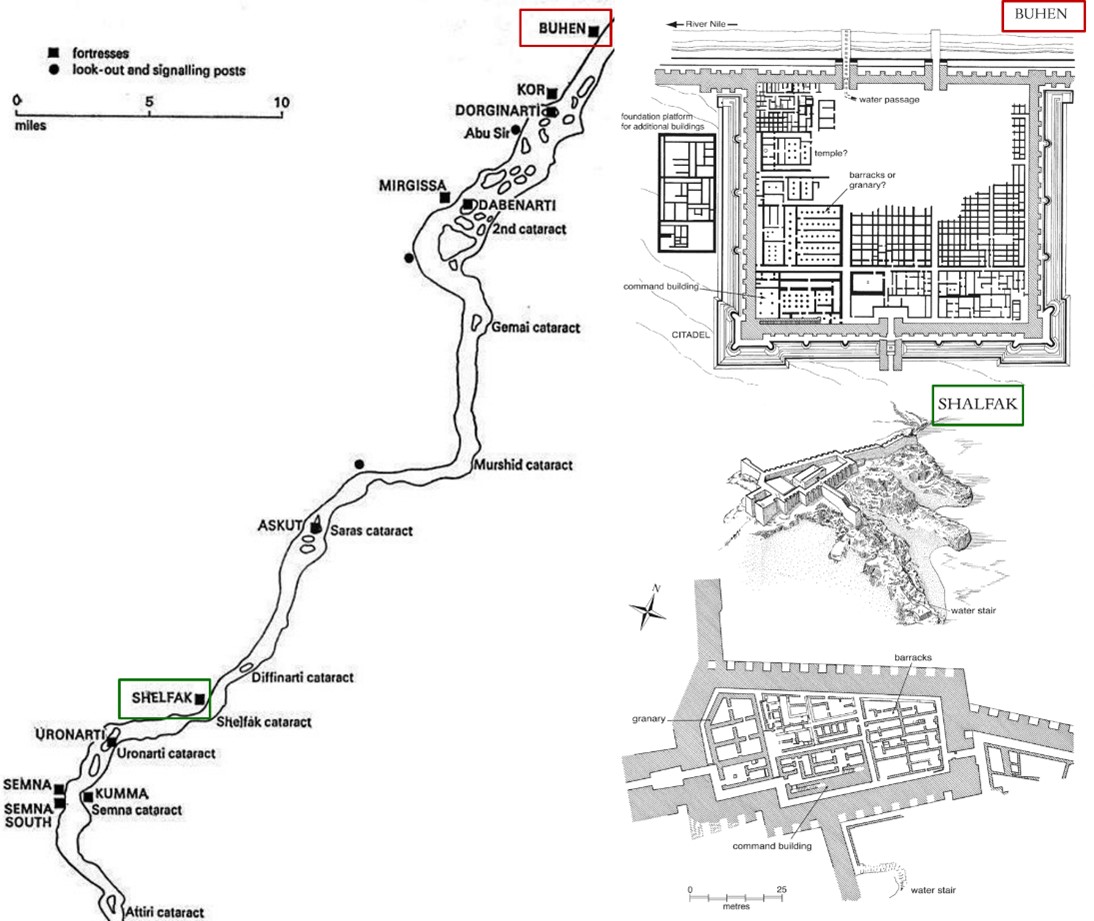

Another evidence about Egyptian settlements comes from the military forts on the border with Nubia, along a territory of ca. 400 km, built during the Middle Kingdom (ca. 2000-1640 BC), mainly at the end of the 12th dyn. (ca. 1974-1715 BC), by pharaohs Senusret I (year 5 of reign, ca. 1967 BC) and Senusret III, ca. 1878-1842 BC (Kemp 1998 Anatomy: 227-238 [20183]). These fortresses, the best preserved are those of Buhen, Shalfak, Semna, and Kumma (Figure 18), are built along the banks of the Nile, on an elevated position, with a rectangular or polygonal plan, with mighty defensive walls, equipped with towers, and have a perfectly orthogonal layout, in several cases, with the urban grid aligned with the gates of the fortress.

Back to top: Birth and Development of Cities

New Kingdom

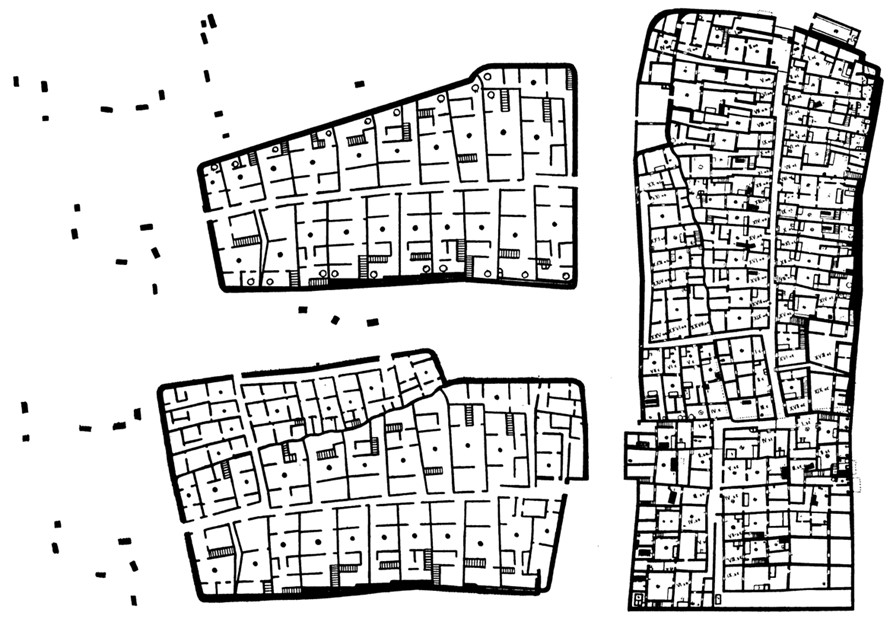

Moving to architecture in the New Kingdom (ca. 1540-1000 BC; see Badawy 1968), we have evidence from the “city of the workers” of Deir el-Medina, ancient Set-Maat (“Seat of Maat”), located near the western necropolis of Thebes (Fairman 1949 Town: 46-49), not far from the Valley of the Kings (Figure 19). The settlement underwent three phases of development: the first and the second respectively at the beginning and the end of the 18th dyn. (ca. 1552-1295 BC) with the Thutmosides (Figure 20, left), and the third, with a powerful enlargement, during the 19th-20th din. (ca. 1295-1188 BC, ca. 1188-1069 BC) under the Ramessides (Figure 20, right; Figure 21). The city shows a rectangular plan with a main road crossing the town longitudinally and dividing the settlement into two zones of dwellings, presenting a clear “standardised model”.

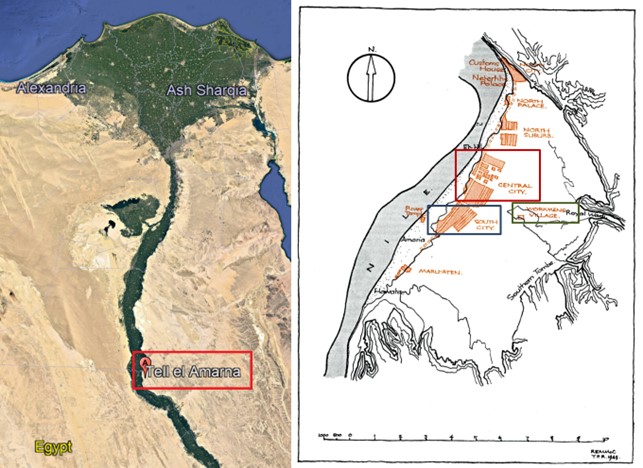

Moreover, during the 18th dyn. (ca. 1552-1295 BC), one of the best known and best documented sites is the city of El-Amarna (Figure 22), ancient Akhetaten (“the horizon of Aton”), the capital built from scratch by Amenhotep IV/Akhenaten (ca. 1352-1338 BC); as it is well-known, the settlement was then abandoned under the successors of the “heretic” pharaoh and for this reason it remained uninhabited and therefore “crystallized” in its last phase of life. The city, delimited by bordering stelae sculpted at regular intervals on the cliffs (Kemp 1998 Anatomy: 328-336 [20183]), has three noteworthy dwelling places: the centre, the southern residential district and the “workers’ village”.

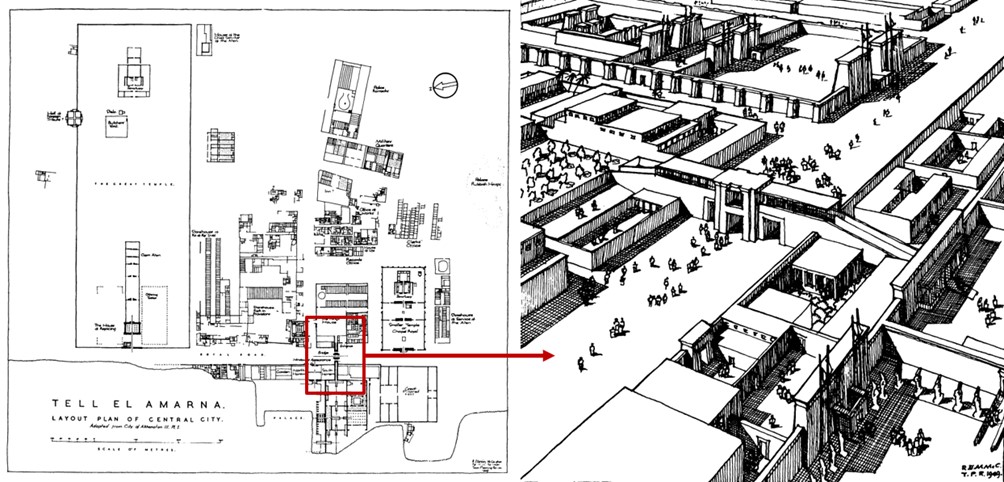

The centre of the city is divided into two parts by the “royal street” leading to the palace, the sovereign’s residence (connected by a bridge) and the Great Hypetral Temple of the Aten (Figure 23); a space with a series of courts and places of representation among which the main one, at an ideological and propagandistic level, was the so-called “window of apparitions”, a place of direct contact of the sovereign with the population.

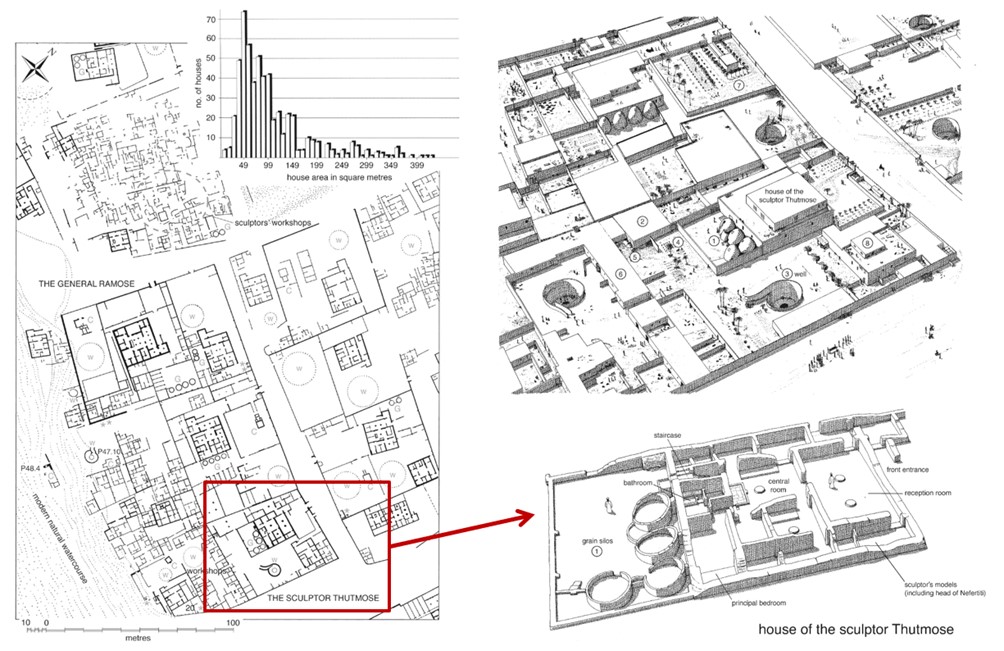

The southernmost residential area (Figure 24) shows a series of houses with a fairly similar layout but with slight variations according to the social level of the owner; these houses have open spaces in front of the actual house, where industrial or artisan activities were located: the most famous case is that of the house of the sculptor Thutmose, author of the bust of Queen Nefertiti, today at the “Neues Museum” in Berlin.

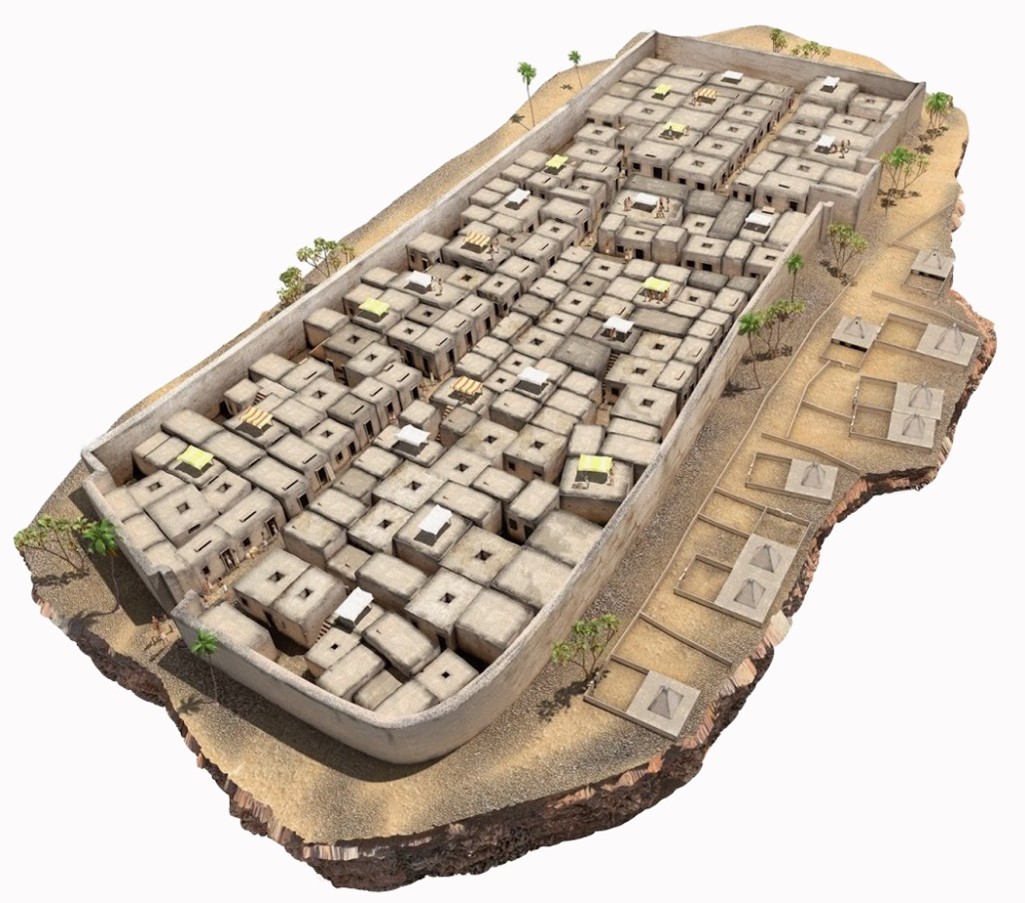

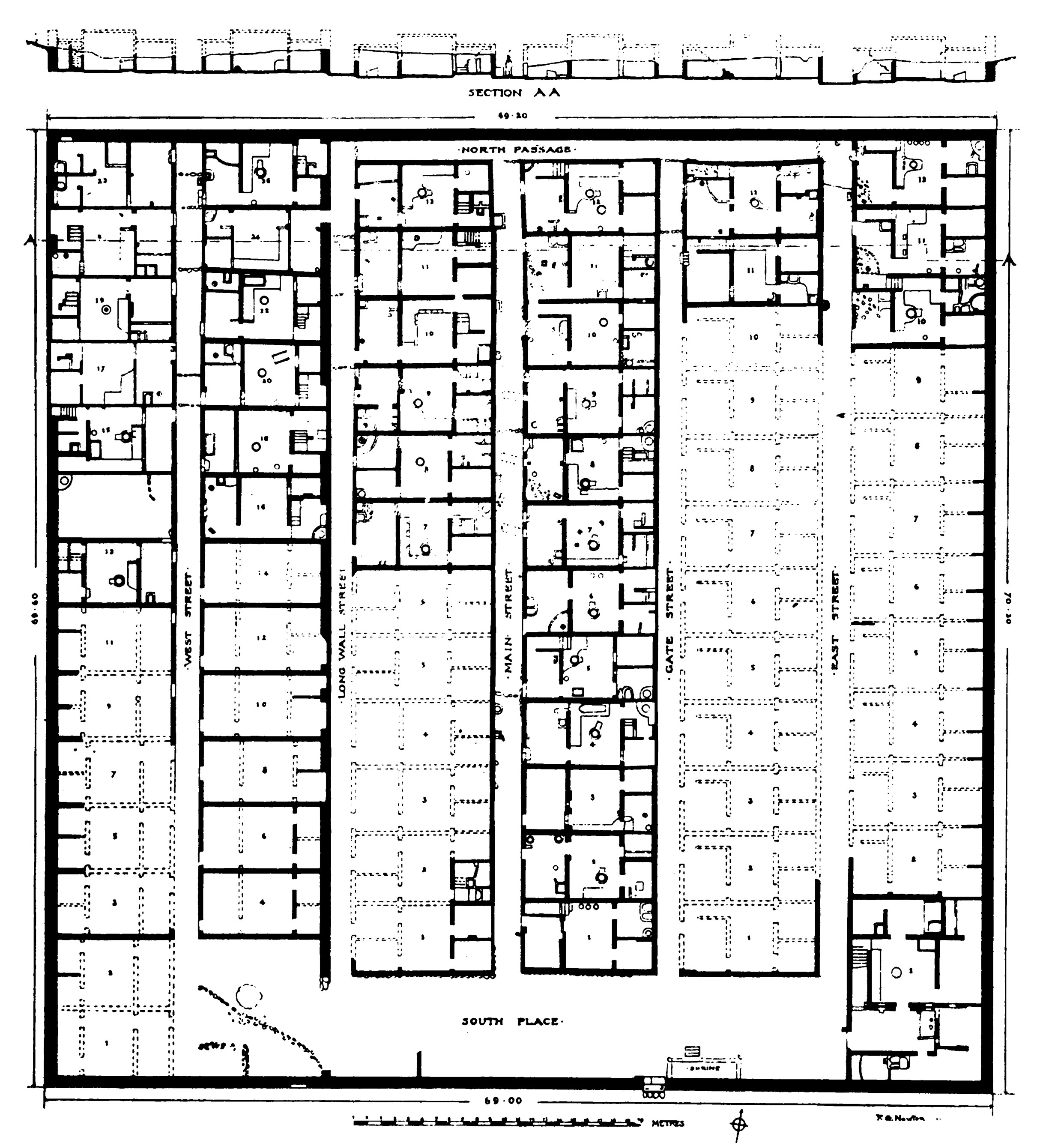

In the “Workers’ Village” (Figure 25), the houses, located at the beginning of the cliff that includes part of the town necropolis, have an almost perfectly squared plan, ca. 69 m per side, and the blocks are divided by five streets oriented N-S: the 72 houses, locked one to the other, are all almost identical, except the one located near to the only gate of the village, along the S-E side, perhaps belonging to the official in charge of the community (see Kemp 1987 Amarna).

Back to top: Birth and Development of Cities

Back to Mesopotamia

Back to top: Birth and Development of Cities

Between Anatolia, Syria, and Assyria

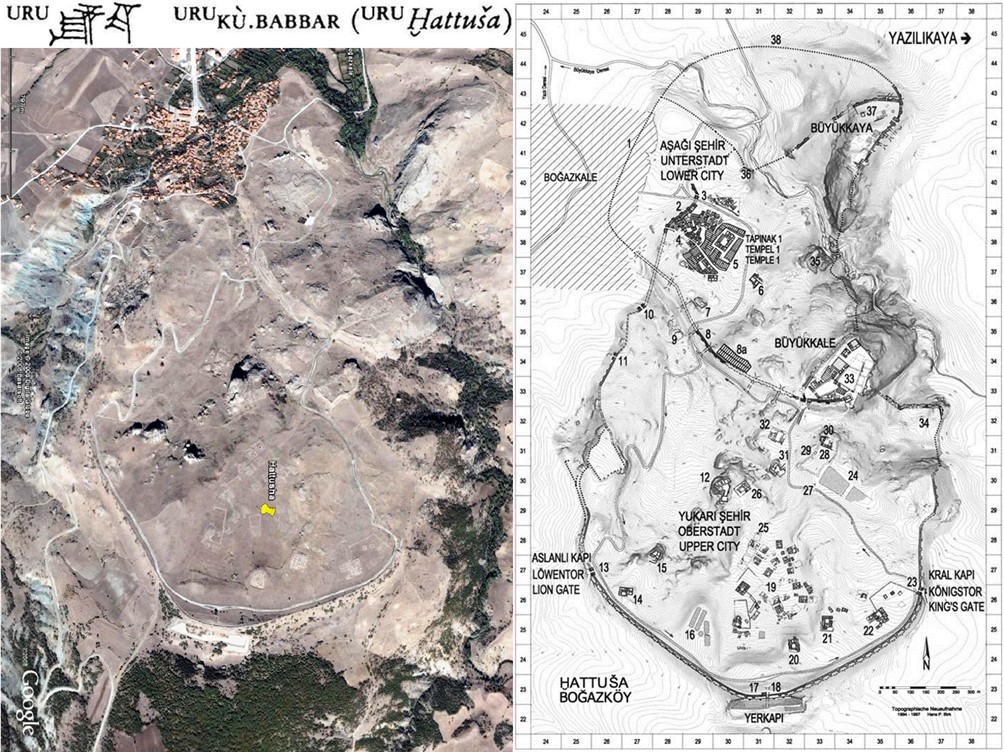

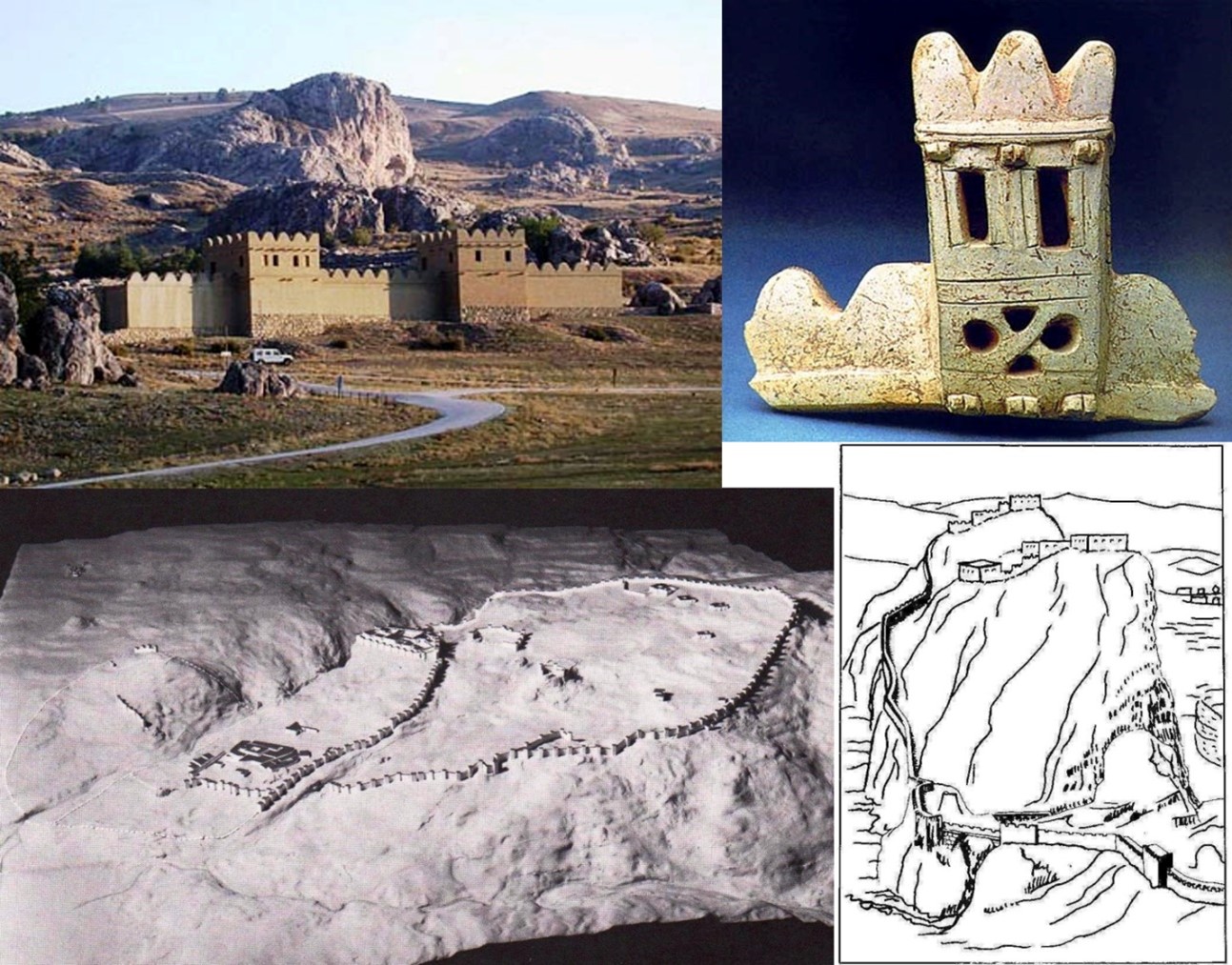

Leaving the sands of Egypt, we suddenly reach the northern-central Anatolia and the remains of the ancient Ḫattuša, located near to the present village of Boğazköy (“gorge village”) / Boğazkale (“gorge fortress”) (Figure 26). The name of the town in cuneiform is usually expressed through the use of the sumerogram URUKÙ.BABBAR (HZL: 125, no. 69) (Figure 27, top-left), formed by the determinative for “town/place name” (URU) in front and KÙ.BABBAR, “silver” (composed of KÙ/KUG, “bright, shiny” and BABBAR, “white, light”). Hittite capital from ca. the 17th century to the 12th century BC, the settlement developed in three areas (Figure 27, right): the “upper town” (south) with a series of smaller temples, the “lower town” (north), with Temple 1 (also called the “Great Temple”) and the royal citadel called Büyükkale, “great fortress”, located in a higher position (Figure 28). A mighty citadel wall (Figure 29), partly rebuilt in recent times, surrounds the entire city, with several entrances, three of which are monumental (in the “upper city”): the “Lion Gate”, to the west (Figure 30, top), the “Sphinx Gate”, to the south (Figure 30, bottom-left), and the “King’s Gate”, to the east (Figure 30, bottom-right).

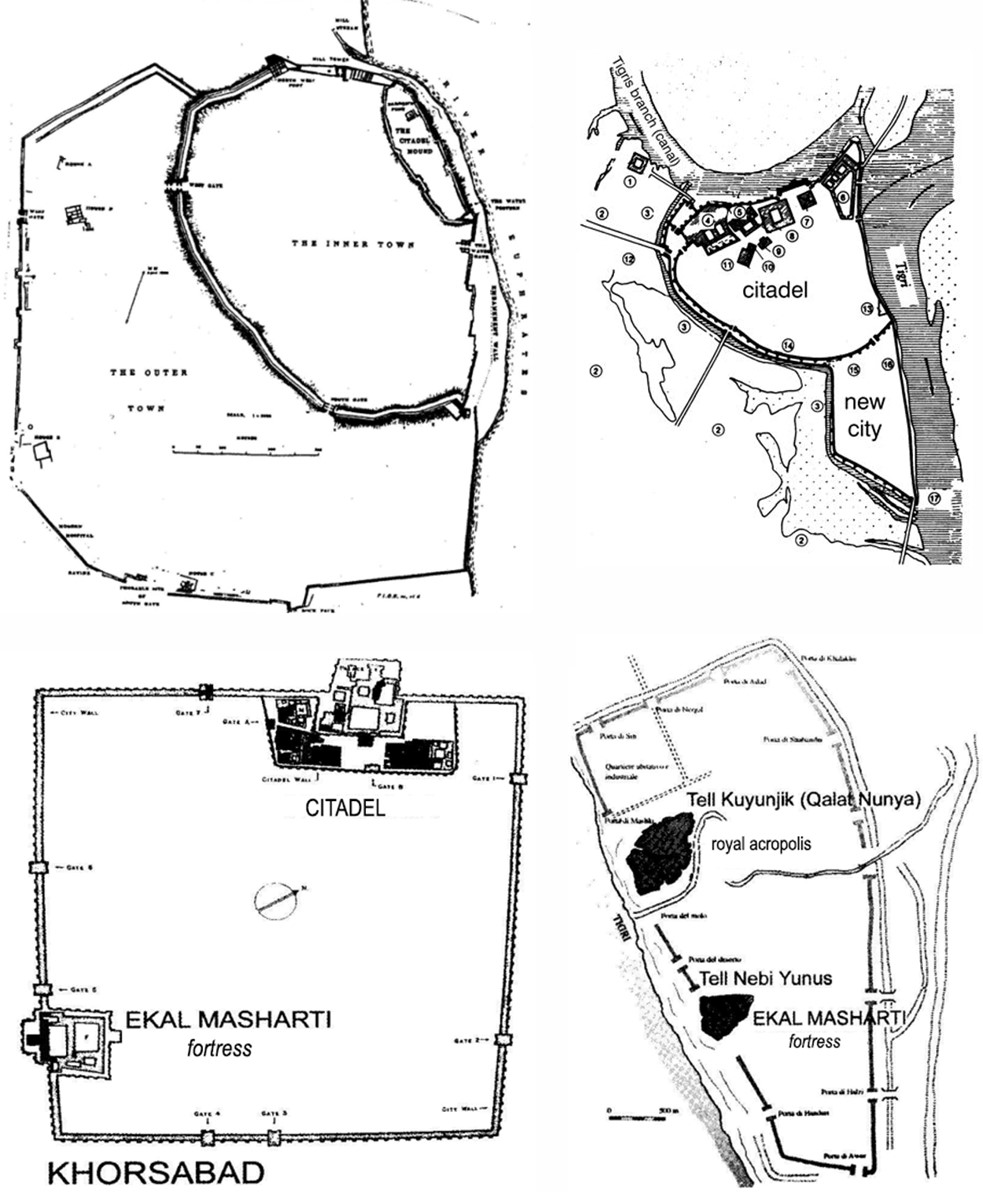

This city structure is also common to other near-eastern cities that distinguish a fortified “citadel”, Akkadian ke/irḫum, (CAD 8: 404-405) and a “lower city”, or “outer city”, Akkadian adaš(š)um. For example, Karkemish (Jarabulus) with the inner city of the Middle Bronze Age (ca. 2000-1500 BC), and the outer city of the Iron Age (ca. 1190-700 BC) (Figure 31, top-left); Ashur/Qal’at Sherqat, with the citadel of the Paleo-Assyrian age (ca. 1950-1750 BC) and the “new city” of the Middle/Neo-Assyrian period (ca. 1360-1050 BC and 725-625 BC) (Figure 31, top-right); Dur-Sharrukin/Khorsabad, founded by Sargon II (ca. 721-705 BC), presenting a well-defined and isolated citadel and the so-called ekal māšarti, “arsenal, fortress” (Figure 31, bottom-left), together with a geometric planning (Battini 2000); Nineveh/Tell Kuyunjiq + Tell Nabī Yūnus, near modern Mossul, built by Sennacherib (ca. 704-681 BC) and enlarged by Assurbanipal (ca. 668-631 BC), presenting a similar division between the royal acropolis, insiting on Tell Kuyunjik, and the ekal māšarti at Tell Nabī Yūnus (Figure 31, bottom-right).

Back to top: Birth and Development of Cities

Babylon

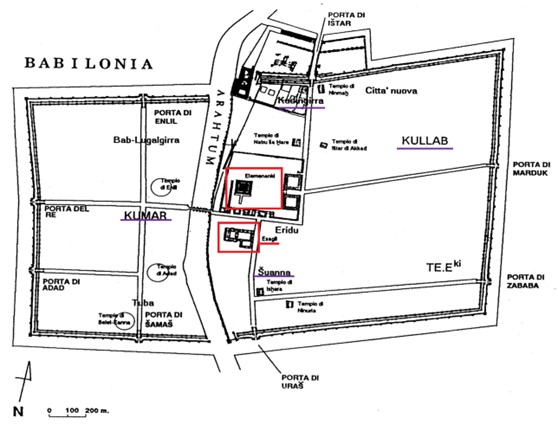

A quick mention also of the city of Babylon, ancient Babilumki (Figure 32), etymologically analysed as bāb ilim/ilī, “gate of the god/gods”, in Akkadian, and KÁ.DINGIR.RAki, “gate of the god”, in Sumerian (Giusfredi 2012 Babilonia: 32-34).

In addition to the imposing ziqqurat, called in Sumerian É.TEMEN.AN.KI, “house of the foundations of heaven and earth”, and the temple of the polyad god Marduk, the Esagil (from Sumerian É.SAG.ÍL, “the house that lifts the head”), both restored in the Neo-Babylonian period by Nabopolasar (ca. 625-625 BC) and completed under Nebuchadnezzar II (ca. 604-562 BC), some specific features in the plan of the city are to be emphasized (cf. Battini 2007 Quelques):

- the division of the city into two parts, due to the passage of a branch of the Euphrates (called Araḫtum);

- the mighty citadel walls;

- the division into quarters named after the oldest Sumerian centers: Kumar (near Eridu), Kullab (part of Uruk), Kadingirra and Shuanna (ancient quarters of Babylon itself); furthermore, also the gates of the city had precise names, e.g. King-Gate, Adad-Gate, Šamaš-Gate, Uraš-Gate, Zababa-Gate, Marduk-Gate, Ištar-Gate, and Enlil-Gate). Not to forget the streets, organised in a fairly orthogonal plan (Battini 2018 Hippodamian), which hosted solemn processions (such as that for the “New Year’s Day”, the akītu) which were named after the gods worshipped in the city, such as Marduk, Nabû, Aiburshabu.

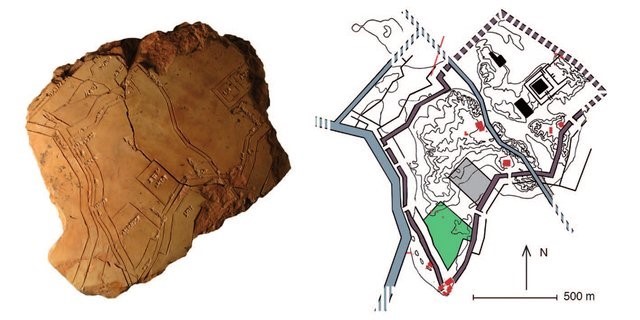

All these features made Babylon a “model city” and a physical-ideological centre of the cosmic order which was definitively canonized in the Chaldean Age (ca. 625-539 BC), as evidenced by the famous Babylonian “World Map” from Sippar (Figure 33, left), dated to the 6th century BC (today at the British Museum, BM 92687).

Back to top: Birth and Development of Cities

Iron Age II in Palestine

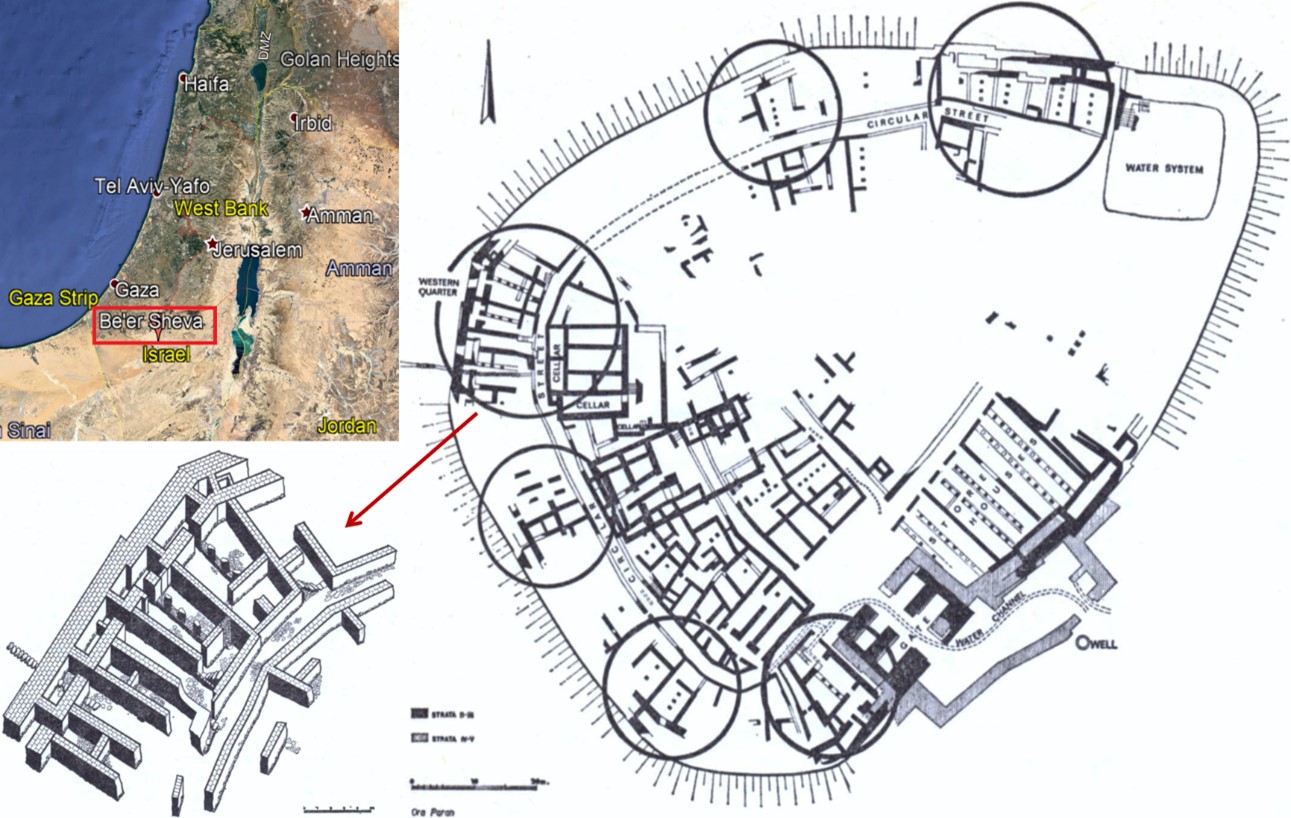

A last remark on a particular development that some Palestinian centres, such as Beersheba (Figure 34), Tell Beit Mirsim, Tell en-Naṣbeh, Beth Shemesh, had during the Iron Age II (ca. 9th-7th cent. BC). These settlements, for the most part not seat of royal power, have a circular plan, a casemate fortification, with the outer dwellings (usually of the “four-room” type) leaning against the walls (Figure 35, top); the central part (Figure 35, bottom), which housed dwellings, buildings of public utility and was separated from the outer houses by a ring road, is defined by Mario Liverani as follows: “This open space is evidently the place of socialization, meeting, rest, in short, of community situations in a settlement of ‘egalitarian’ communities (i.e. not centralized on a palace)” (Liverani 2012 Fondazioni: 10; English translation by the author).

Back to top: Birth and Development of Cities

Conclusions

This brief excursus allows us to conclude that in Ancient Near East and Egypt there was not a single model of city, but rather a series of different urbanistic conceptions, differently declined according to place, culture and material needs of the individual communities; as far as these communities, their political systems, their needs changed, thus also the town plan evolved, improved, and reshaped itself, showing a dynamism which clearly denotes the fluid necessities of the people living in those cities.

Back to top: Birth and Development of Cities

Figures

Back to top: Birth and Development of Cities