Back to top: Part IV Chapter 16

16.1 At the Margins of the Territorial System

The political sistem of the territorial states (cf. Sections 6 and 7) was able to foster a sensitivity for the social and cultural aspects of the broader area: ‘Sumer and Akkad’ and the ‘four river banks’ are now understood as not just a geographical area but also a civilization in which cultural unity transcended geographical boundaries.

The previous ‘empire’ of Akkad (cf. Section 8) did not include the entire ecumene: on the margins of urban Mesopotamia still to be ‘invented’ in the Mesopotamian mindset even if they had been already ‘invented’ according to their own standards (cf. Section 14.6).

There were three main typologies of social entities:

- the interactive margins, having regular exchanges with the Mesopotamian ‘core’; they were agropastoralist people (cf. Sections 16.3-8);

- the splinters, detached from the territorial structure, known as ʿābirū, i.e. ‘fugitives’/’stateless’(cf. Section 16.9);

- the remote margins, without relationships with Mesopotamia, seen as unknown foreigners: these are the people of the mountains (cf. Section 16.10).

Back to top: Part IV Chapter 16

16.2 People and Territory

All the aformentioned entities share a common feature: they had a perception of distance with regard to the notion of settlement.

The population of the interactive margins was distant, even if just temporary, from their base settlements. Here, a new para-perceptual model started, transcending the face-to-face relationship: the notion of kinship bond. This dynamics led to the formation, with the Amorites (cf. Section 16.8), of the tribe as a counter-state (cf. Section 16.6).

The splinters were people who, after leaving their urban territory, are in search of an equivalent territory. In the documents, the ʿābirū are described as migrants if not ‘terrorists’ who disappear once the great system encompasses them.

The remote margins, as the Kassites, were still not urbanized and retained a concept of the territory similar to that of the prehistoric periods.

Back to top: Part IV Chapter 16

16.3 Pastoralism

The steppe was already inhabited in the paleolithic period by human groups who did not develop a control of the territory on a regional level.

With the progressive drying of these regions, the human groups moved towards the basin of the great rivers and, from the second half of the third millennium BC, developed a new pastoralism.

This phenomenon took the shape of a para-urban expansion, a form of ‘retro-expansion’, particularly in the area of the middle Euphrates which is charatcterized by a long corridor delimited on either side of the river (the ‘forehead of the Euphrates’, for which cf. Section 10.2). In this semi-arid, non-irrigable area (see Map 2), where irrigation was not that developed and agriculture was limited, we find at any given point of time just a sigle important center, the most important of which was Mari (cf. Section 6.11.2). This area was known as aḫ Purattim in Akkadian (literally, ‘the flank of the Euphrates’), the equivalent of the modern Arabic term zôr (cf. Section 10.5).

The development of the steppe was made possible by two climatic factors:

- the precipitations in the springs were sufficient to maintain a vegetation ideal for pasture of sheep, goats, and donkeys;

- the groundwater was easily accessible and, again, ideal for animals.

Thus, the population of the middle Euphrates ‘invented’ the steppe (cf. Section 11) as a perfect environment for their flocks, an area, characterized by the relief and the few oases, untouched also from the ‘empire’ of Akkad (Section 11.2).

The people of the middle Euphrates, mostly shepherds, reached a new para-perception of the landscape which did not change in its nature (-etically) but just on the level of perception (-emically).

Back to top: Part IV Chapter 16

16.4 Nomadism

Two terms, referring to the use of resources and the way of habitation, are characteristic of this new setup of the landscape:

- ‘mobility’: the dwelling is not permanent;

- ‘nomadism’: the use of pasture as an economic resource (the term ‘nomads’ comes from the Greek word for ‘grazing’, i.e. νέμειν, némein).

The shepherds of the steppe followed the course of the seasons and, moving with their flocks, were used to live in ‘hair houses’, i.e. tents. They were also dependent on the river plains for two reasons:

- this was they place of origin anchored to family relationships and landed property

- it was the place from which they could procure goods not available in the steppe.

Hence, the life of these ‘interactive margins’ was characterized by a ‘dimorphic’ system of semi-nomadism.

The indigenous terms for ‘nomads’ in the local dialect are geographically connotated by the refernce to the position along the Euphrates (looking downstream):

- yamina, ‘right’, for the western part of the steppe;

- sam’al, ‘left’, for the eastern part.

The belonging to a determinate geographical element in the definition of the nomads (and not of the tribes) was expressed with the image of filiation (cf. the Akkadian construct mārū ugārim, ‘sons [of the] irrigation district > farmers’), with the term banū (related to the rural sphere), equivalent to the Akkadian mārū (more connected to the urban background), both meaning ‘sons (of)’:

- bānū yamina = mārū yamina (Akkadian) = ‘sons (of the) left’;

- bānū sam’al = mārū sam’al (Akkadian) = ‘sons (of the) right’;

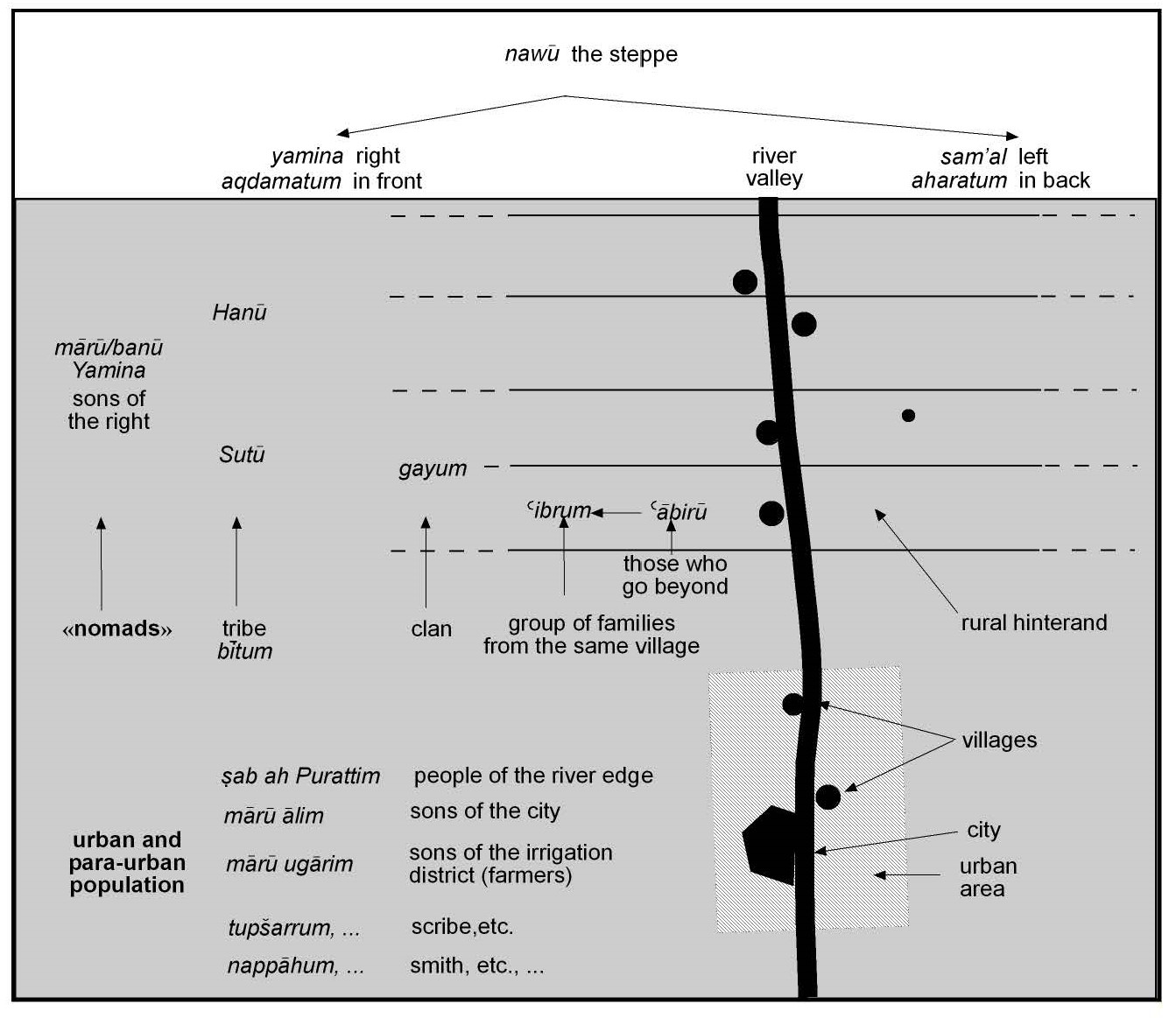

Other two geographically connotated terms of the local dialect were used to refer to the two regions (having as focal point an observer looking downstream; cf. Figure 7):

- aqdamatum, ‘the part in front’ = the region to the right (i.e. western steppe);

- aḫaratum, ‘the part behind’ = the region to the left (i.e. eastern steppe).

The sedentary population generally looked at the way of life of the nomads in negative tones, as people without a city, a house, residing in tents, uncapable of cultivating grain; digging up wild mushrooms from the mountains, eating uncooked meat, living ravaging as dogs or wolves.

The process of nomadization strongly affected people’s social (16.5) and political conditions (16.6), a turning point in the institutional dynamics of the ancient Syro-Mesopotamian area.

Back to top: Part IV Chapter 16

16.5 Social Structure

The associative mechanisms of people in the steppe had their starting point in two features:

- isolation (the point of origin of the group is far);

- aggregative impulse not based on the territory (as it was for the urban revolution) but on bonds of kinship.

On this basis, three associative levels emerged (cf. Figure 7):

- the group of those who had ‘gone beyond’ from the fluvial plain to the steppe: ʿibrum (from the root ʿbr, Akkadian ebērum; people of this group were connected through agnatic relationships of real biological kinship; at this level, there is still a sense of immediate solidarity;

- the gayum, an aggregate of groups of the first type, as a clan where solidarity is mediated by regular meetings;

- the tribe, bītum, literally ‘house’ (but even implying the wider semantic spectrum of household), used from the Aramaic period (cf. Section 21.8); during the Amorite period, we have attestations of proper names as ʿanū and Sutū for the Khanaeans and the Suteans, respectively.

On this structure, a sense of identity emerged through ties of solidarity and the relationship to the territory.

As a proper name, at the end of the third millennium BC, the Sumerian MAR.TU, equivalent to the Akkadian Amurru(m) (literally, ‘the westeners’) became the common term to refer to the people of the steppe (cf. below, Section 16.7).

Schematic rendering:

cities (polygon) and villages (circles) are only in the river valley,

where there are differentiated social and professional classes;

agro-pastoralists expand from the rural areas of the river valley towards the steppe

and give rise to new social groups which eventually become a tribe

Back to top: Part IV Chapter 16

16.6 The Tribe as a Counter-State

The difference between the tribe and the territorial state (cf. Sections 11.4, 12.4 and 16.2) resides in a different declination of the concept of solidarity.

Within the tribe, the presence of a strong kinship bond helped in maintaining direct relationships between people, favoring these personal relationships over the functional ones (typical of the territorial states); in this regards, the tribe can be perceived as a counter-state.

About the internal structure of the tribe we know very little, but we can pinpoint some peculiar and important figures:

- the abum, the ‘father’, who retained a political power;

- the ‘elders’, having specific administrative functions.

What is also important to stress is the lack of any scribal system and scribal tradition within the tribal structure.

Even though, the use of the title ‘king of Mari and Khana’ applied to the king of Mari, reflects the importance of the tribe (the Khanaeans) also in the wider framework of the middle Euphrates territorial states.

The Biblical narrative about the installation of the monarchy (1 Sam. 8) also mentions the ‘elders of Israel’, who, complaining about the behavior of the two sons of Samuel appointed as judges, asked for a king; this is an evidence to the passage for the status of the tribe to that of a territorial state, implying a consious choice that included the acceptance of a functionalization of individuals (see 1 Sam. 8:12).

Back to top: Part IV Chapter 16

16.7 The Tribal Revolution

Two factors must be stressed in the structure and development of the tribe:

- its emergence as a political institution competing with the structure of the territorial states, counter-balancing the phenomenon of depersonalization of the individual;

- the role of the rural population, re-enacting the para-urban Neolithical dynamics which had led to the formation of the first cities (cf. Section 1.3) and to the first process of ‘industrialization’ (cf. Section 5.12).

It was indeed a tribal revolution, lasting for a short time but havinh three important consequences:

- a true conquest of the steppe;

- the formation of a model of the tribe as a political entity, influencing the later Aramaic tribes (cf. Section 20.4) and those of ancient Israel (cf. Section 21.8);

- the configuration of Amurru as the first territorial state of the steppe (cf. Section 20.6).

Back to top: Part IV Chapter 16

16.8 The Amorites

‘Amorites’ can be regarded as a collective name denoting these new political entities in the steppe (see Map 13, connotated by a relevant linguistic dimension, which is accessible to us through onomastics attested in documents from city archives.Note 1

The Author of the present essay, interestingly, considers the Amorite language not just as a northwest Semitic dialect but rather as an archaic form of Akkadian confined in the steppe region (cf. above 16.4) and opposed/complementary to the Akkadian spoken in the cities.

Amorite onomastics was also retained when Amorite dynasties left the steppe to ‘re-conquer’ the city dimension; just think of the dynasty of Hammurapi, an Amorite name [cf. Section 14.5 with fn. 1], at Babylon: here, the king, despite he spoke Babylonian Akkadian, still retained his originally Amorite name.

Back to top: Part IV Chapter 16

16.9 The Splinters: Fugitives and Migrants

Beyond the political and geographical horizon of the territorial states, some centrifugal movements developed, especially in the ‘cosmopolitan period’ (cf. Part V), later put under a full control only with the empires (cf. Part VI).

The process of nomadization (cf. 16.4), leading rural population to leave cities towards the steppe, was an effective way to escape the centralized control of the state.

This phenomenon of ‘passing’ from an old to a new dimension is well described by the root ʿbr (related to the Akkadian ebērum), literally ‘to go beyond > to pass, on which the Amorite term ʿibrum (‘gone beyond’) was coined, with the meaning of ‘extended family’ of the clan (gayum). The single individual of this new socio-political component was then defined as ʿābirum (in Akkadian), ‘he who passes.’ This is indeed the proper form of the term usually rendered as ḫapiru(m), a form reflecting the cuneiform graphic system but that cannot be justified phonemically.

In short, an ʿābirum was a person who passed from the river valley to the steppe, from the village to the ʿibrum (‘extended family’); these people are hence, at the same time, fugitives with regard to the city and transients with regard to the steppe, stateless people without a suitable legal state.

This was also the situation of the ʿibrîm, the ‘Hebrews’, a gentilic adjective (ʿibr-ī-um), derived from the original noun ʿibr-um, which is first attested in Old Babylonian texts of this period.

Many times, the ʿābirū, were regarded as isolated bands within other states which reacted to this new phenomenon on a structural level (cf. Section 19.4).

Back to top: Part IV Chapter 16

16.10 The Remote Margins: The People of the Mountains

The relationship between urban regions and the people of the north-eastern mountains remained less interactive and constant.

The invasion by the Gutians (cf. Section 12.4), ‘replicated’ later on by the Kassites (cf. Section 18.5), is a clear evidence of this geographical and structural distance.

We can, in fact, speak of a non-interactive relationship (different to that with the steppe) with the ‘remote margins’ of the Mesopotamian geographical mindset (mainly involving, in this case, the Iranian and the Zagros areas).

Differently, the mountains in Anatolia remained instead closer to the valleys of the highlands, thanks to commerce and ethnic affinities (because of the Hurrian presence in south-eastern Anatolia, mostly in the later area of Kizzuwatna, close to the core of the kingdom of Mittani).

Back to top: Part IV Chapter 16

16.11 Centrifugal and Allogenic Impulses

The centrifugal impulses of the remote margins affected the territorial system of the territorial states, acting as allogenic elements. The term ‘allogenic’ has to be interpreted as a dimension intrinsecally and structurally at variance or even in opposition with the territorial states.

In the end, the interaction between these profoundly different political organizations led to the collapse of the first regional system.

These centrifugal impulses were operative in three different areas:

- the tribes in the steppe (and, above all, the Amorites) acted as a centrifugal factor in detaching people for the mid-central basin of the Euphrates; the Amorites, in effect, developed as an autonomous and self-aware population (this situation will radically change in the mid-second millennium; cf. Section 20.5);

- the ‘splinters’, the ʿābirū, were a centrifugal and also allogenic factor in limiting the territorial control of the state, leading to disaggregative phenomena;

- the Kassites were an exclusively allogenic factor, installing themselves in the southern regions (after the fall of the Old Babylonian kingdom because of the Hittite campaigns of Mursili II, ca. 1595 BC; Section 17.2), establishing the longest dynasty in Babylon (the so-called Middle Babylonian kingdom), being capable of “fully integrating themselves in the social and cultural fabric of Babylon […] (reshaping) the core from within” (Buccellati, Origins, p. 204).

Back to top: Part IV Chapter 16

Notes

- Note 1: on Amorite onomastics, see mainly Buccellati 1966 Amorites. Back to text

Back to top: Part IV Chapter 16