Cf. Bucellati, Origins, section 10.7.

Back to top: “Mesopotamia”

Introduction

This theme aims at re-discussing the origin and meaning(s) of the Greek term Μεσοποτᾰμία, ‘Mesopotamia’.

Back to top: “Mesopotamia”

Greek sources (exogenous)

‘Mesopotamia’ is not a Mesopotamian term, but a Greek one, meaning ‘the land between the two rivers (ἡ μέση τῶν ποταμῶν > Μεσοποτᾰμία, a de-adjectival nominalization coined on the adjective μεσο-ποτάμιος, ‘between rivers’; see L S J, sub voce).

The term has been ‘coined’/first attested in Arrian’s (ca. 86/89 – after 146/160 AD), Anabasis of Alexander (Ἀλεξάνδρου Ἀνάβασις)Note 1; in An. 7:7.3Note 2 Arrian states that:

(Finkelstein 1962 Mesopotamia, p. 73)Note 3

- the name refers to that part of Syria situated between the Euphrates and the Tigris, and

- the name was that given to the territory in question by the inhabitants.”

The same explanation can be also found in Arrian’s Ἰνδική, Indica 42:3:Note 4

“ὁ Τίγρης [...] ὃς ῥέων ἐξ Ἀρμενίης παρὰ πόλιν Νῖνον, πάλαι ποτὲ μεγάλην καὶ εὐδαίμονα, τὴν μέσην ἑωυτοῦ τε καὶ τοῦ Εὐφράτου ποταμοῦ γῆν Μεσοποταμίην ἐπὶ τῷδε κληίζεσθαι ποιέει.

It [the Tigris] flows from Armenia past the city of Ninus [Nineveh],3 once great and prosperous, and gives the region between itself and the Euphrates the name of Mesopotamia (between the rivers).”

(Brunt 1996 Indica, pp. 426-427)

According to Finkelstein 1962 Mesopotamia, p. 73, “although the Greek place-name ‘Mesopotamia’ was first coined in Alexandrian times and designated a more or less strictly delimited administrative district, the name itself was presumably translated from the term already current in the area – probably in Aramaic – and apparently was understood to mean the land lying ‘between the (Euphrates and Tigris) rivers’” (cf. following section).

Back to top: “Mesopotamia”

Semitic sources (endogenous)

Interestingly, a same meaning is in the Arabic بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن Bilād ar-Rāfidayn or بَيْن ٱلنَّهْرَيْن Bayn an-Nahrayn, the Persian میانرودان miyân rudân, and the Syriac ܒܝܬ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ Beth Nahrain ‘(land) between the (two) rivers’; cf. attestations in the Peshitta).

The term has been argued to be a calque of the older Aramaic term byt nhryn, for which cf. also the glossa בּין נהרין, byn nhryn, in the Apocryphon of Gen. 14:1 (i.e. Qumran scroll 1Q20 = 1QApGen; see Finkelstein 1962 Mesopotamia, p. 74; edition in Avigad & Yadin 1956 Apocryphon; commentary in Fitzmyer 1966 Genesis; cf. also the interesting discussion in Muraoka 1972 Genesis, pp. 18-19, §6.3Note 5).

Moving backwards in time, “the question of pre-Aramaic equivalents for the name presents itself, and specifically, the possible designations for the area in Akkadian sources, i.e., in the language which was continuously written or spoken in the area for perhaps two millennia earlier than the Aramaic” (Finkelstein 1962 Mesopotamia, p. 74).

The Aramaic term itself could be a calque (not semantically but at least conceptually) of the Akkadian birit nāri(m) for which see, e.g., Finkelstein 1962 Mesopotamia, p. 74 (cf. also the Egyptian toponym ‘Naharina’, referring to the area of Mittani, i.e. Egyptian nhrn, a loanword from Semitic: see Wb, 2.287.1; cf. Hoch 1994 Semitic, no. 253).

Finkelstein wrote on this regards: “Against this background, the present writer called attention a few years agoNote 6 to certain geographical references in Old Babylonian contracts involving the sale of slaves which appear to represent the very Akkadian antecedent for the name ‘Mesopotamia’ and the Aramaic byn nhryn. In one of these contracts the slave is described as coming from the city of Šinaḫ which is in a ma-at Bi-ri-timki, clearly proper name, that may be understood literally as ‘Between-land.’”

In another contract a slave is similarly said to derive from libbi ma-at(!) Bi-ri-tim, without apparent mention of a particular city. A variant designation for the same territory, bi-ri-it nārim (ÍD) was found in another, unpublished contract, in which the city of Ašlakkā, the origin of the slave in question, is said to be situated (Finkelstein 1962 Mesopotamia, p. 74).

Finkelstein also noticed how the term ma-at Bi-ri-ti in VAT 819, l. 1, a contract for the sale of a slave (see Finkelstein 1962 Mesopotamia, p. 75) dated to the 11th year of Samsu-ditana, ca. 1625–1595 BC) could be understood as referring to the land later labelled ‘Mesopotamia’: “the land of Bīrītum: ‘Mesopotamia’ denoted a relatively limited territory, namely, the land within the bend of the Euphrates” (Finkelstein 1962 Mesopotamia, p. 76).

Thus said, the geographical term māt Bīrītim requires to be further investigated, as pointed out in Finkelstein 1962 Mesopotamia, p. 78: “When we survey all the known topographical data concerning cities explicitly situated by the ancient sources in ‘Mesopotamia,’ a geographical pattern begins to emerge which suggests that the traditional understanding of ‘Mesopotamia’ as the land ‘between the Tigris and Euphrates’ requires critical scrutiny.”

The result, considering the location of the cities mentioned in the examined text, is as follows:

“Yet it is doubtful that the source of the name 'Mesopotamia' is to be sought along these lines. For while the Tigris is to be ruled out of consideration in this connection on the basis of known evidence, one can nevertheless easily understand that the importance of the river, and its equal footing with the Euphrates in the experience of the local inhabitants would have justified the popular explanation of the name 'Mesopotamia' even before the Alexandrian age, our earliest clear evidence for the traditional interpretation. Neither the Khabur nor the Baliḫ is such an over whelming geographical feature, both being in fact tributaries of the Euphrates itself.”

(Finkelstein 1962 Mesopotamia, p. 79)

Consequently, Finkelstein advanced and interesting suggestion:

“Is it possible that the names for 'Mesopotamia' in the earlier languages, such as Naharayim and its variants, and Bīrītim and its variant forms, connoted originally some association with one river -- the Euphrates -- and not at all with two rivers as the name has been understood since the Alexandrian age?”

(Finkelstein 1962 Mesopotamia, p. 79)

This hypothesis is basically built on two points:

“(a) Geography. It was already shown above that in all cases for which we have clear evidence for the location of a city in 'Mesopotamia' it is in the far western part of the "Jazireh" that such localizations are indicated, and none east of the Upper Khabur triangle.

(b) Terminology. There is nothing in the formation of the different names for the area in question that compels us to explain them in terms of more than one river. The Greek actually occurs in the *μεσοποταμία* meaning the midst of the river,' while the explanation of naharayim as a dual formation is open to serious question, as will be indicated below. But the most important indication that we must conceive of the names as dealing essentially with one river occurs in the explicit localization of the city of Ašlakkā, bīrīt nārim, i.e., with the singular for the word 'river.'”

(Finkelstein 1962 Mesopotamia, p. 79)

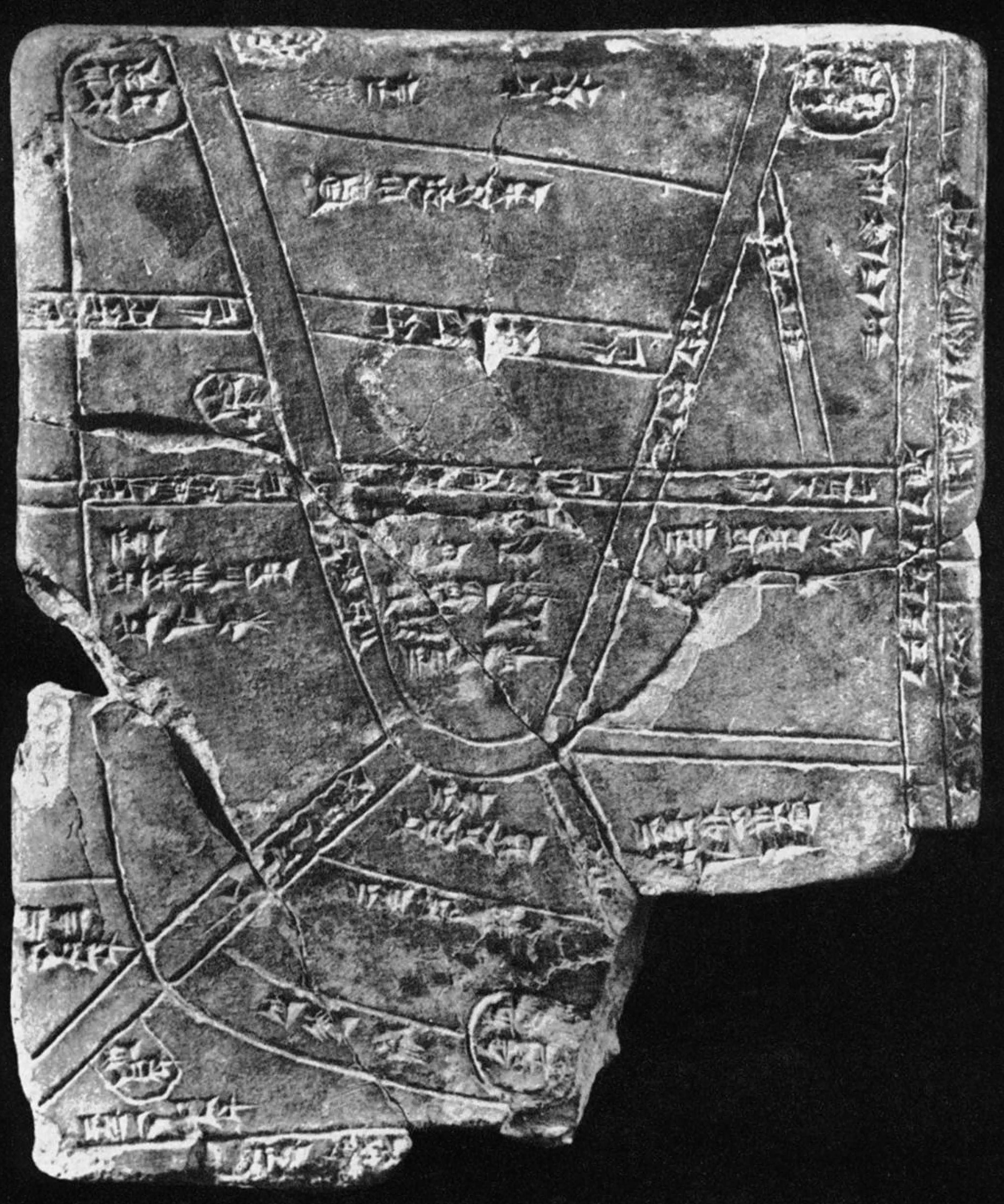

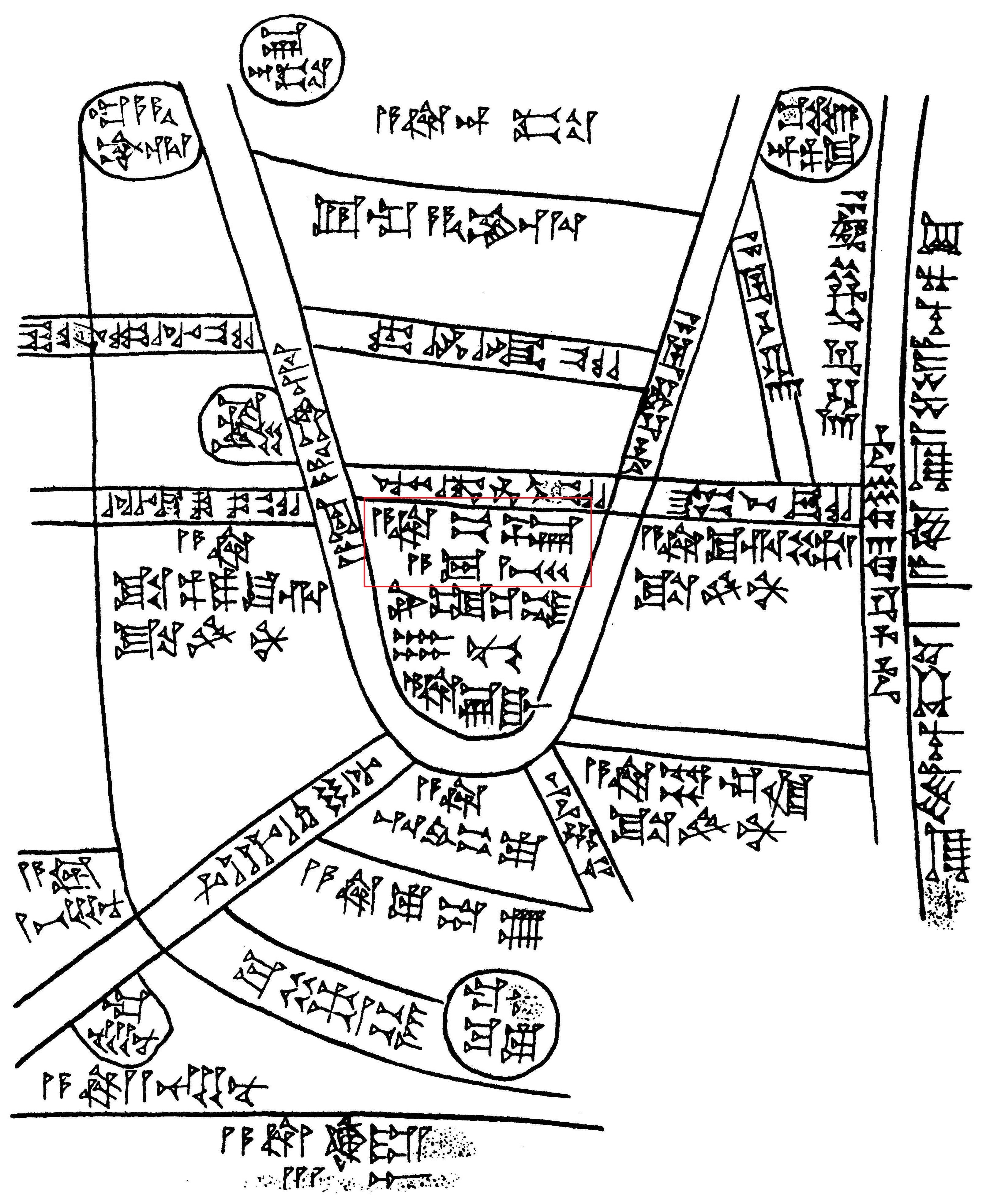

Moreover, by analyzing a Kassite map of the fields in the vicinity of Nippur (University of Pennsylvania Museum, CBS 13865; Figures 1 and 2) Finkelstein argued that “the field at the center of the diagram is labelled A·ŠÀ bi-rit ÍD·MEŠ. The field takes its name from the fact that a continuous stream flows around it in a U shape, turning the field, as it were, into a ‘peninsula.’ The fact that the two ‘arms’ of the U-shaped stream go by different names, Ḫamri and Eššuti (BÍL)ti respectively, explains the use of the plural for ‘rivers’ in the name of the field. Had the entire stream gone by one name, it is obvious that the field would have been called simply A·ŠÀ bi-rit ÍD. In either case, the meaning of the description is the same, a ‘peninsular field.’ The fields figuring in the various contracts described as situated ina bīrītim or bīrīt nārim must also be understood as ‘peninsular’ […]” (Finkelstein 1962 Mesopotamia, p. 81).

(after Finkelstein 1962 Mesopotamia, p. 81, pl. X)

(after Finkelstein 1962 Mesopotamia, p. 80, fig. 1)

Hence, here if Finkelstein conclusion:

“When we next turn to the possible application of this description to the territory of 'Mesopotamia,' there can be no mistaking the feature to which it refers: the Great Bend of the Euphrates, U describing a shape, inclosing the land within the bend as a great peninsula. In short, the name Māt Bīrītim and Bīrīt Nārim, i.e. 'Mesopotamia,' in its original and strictest connotation, refers to that territory surrounded on three sides by the great bend of the Euphrates; no other river or stream is involved in this name. If it would be ascertained how far to the east speaking, only the westernmost tributaries of the Khabur would properly fall within the limits of the territory understood to be Māt Bīrītim [...]” (Figure 3).

(Finkelstein 1962 Mesopotamia, pp. 81-82)

(after Finkelstein 1962 Mesopotamia, p. 82, fig. 2)

To conclude: “We have, in short, in the terms (māt) bīrītim and bīrīt nārim, the Akkadian equivalents for ‘peninsula,’ or, more specifically, ‘riverine peninsula.’ Classical Mesopotamia represented probably the best-known example of this geographical feature, but the terms were equally applicable to any area of the same topographical configuration, whether some territory surrounded by the arm of a river, or some parcel of a field similarly surrounded by a canal or canals” (Finkelstein 1962 Mesopotamia, p. 83).

Back to top: “Mesopotamia”

Bibliography

Cf., as possible sources for further developments:

- Beth Nahrain (as a modern comparison);

- Smith, Mark S. and Bloch-Smith, Elizabeth M. 2021, Judges 1: A Commentary on Judges 1:1 Ð 10:5, Minneapolis (MN): Fortress Press, p. 209.

- Muraoka, Takamitsu 1972, “Notes on the Aramaic of the Genesis Apocryphon”, Revue de Qumrân 8/1, pp. 7-51 (12, 16-17, 19 [fn. 44]); p. 19: “(3) The traditional concept of Mesopotamia “between the two rivers” is the result of a later secondary developmet”.

- Finkelstein 1962 Mesopotamia (basic reference in literature; see mainly the discussion at pp. 78-83).

Back to top: “Mesopotamia”

Notes

- Note 1: for an English translation, see Chinnock 1884 Anabasis; Greek text available online on Perseus at this link; an English translation can be also found online. Back to text

- Note 2: English translation available here. Cf. also the interesting remark in Chinnock 1884 Anabasis, p. 380, fn. 1: “The Greeks and Romans sometimes speak of Mesopotamia as a part of Syria, and at other times they call it a part of Assyria. The Hebrew and native name of this country was Aram Naharaim, or ‘Syria of the two rivers.’” Back to text

- Note 3: see An. 7:7.3-5 in Brunt 1996 Anabasis : ” (3) Τῶν γὰρ δὴ ποταμῶν τοῦ τε Εὐφράτου καὶ τοῦ Τίγρητος, οἳ τὴν μέσην σφῶν Ἀσσυρίαν ἀπείργουσιν, ὅθεν καὶ τὸ ὄνομα Μεσοποταμία πρὸς τῶν ἐπιχωρίων κληΐζεται, ὁ μὲν Τίγρης πολύ τι ταπεινότερος ῥέων τοῦ Εὐφράτου διώρυχάς τε πολλὰς ἐκ τοῦ Εὐφράτου ἐς αὑτὸν δέχεται καὶ πολλοὺς ἄλλους ποταμοὺς παραλαβὼν καὶ ἐξ αὐτῶν αὐξηθεὶς ἐσβάλλει ἐς τὸν πόντον τὸν Περσικόν, μέγας τε καὶ οὐδαμοῦ διαβατὸς ἔστε ἐπὶ τὴν ἐκβολήν, καθότι (4) οὐ καταναλίσκεται αὐτοῦ οὐδὲν ἐς τὴν χώραν. ἔστι γὰρ μετεωροτέρα ἡ ταύτῃ γῆ τοῦ ὕδατος οὐδὲ ἐκδίδωσιν οὗτος κατὰ τὰς διώρυχας οὐδὲ ἐς ἄλλον ποταμόν, ἀλλὰ δέχεται γὰρ ἐκείνους μᾶλλον, (5) ἄρδεσθαί τε ἀπὸ οὗ τὴν χώραν οὐδαμῇ παρέχει. ὁ δὲ Εὐφράτης μετέωρός τε ῥεῖ καὶ ἰσοχείλης πανταχῇ τῇ γῇ, καὶ διώρυχες δὲ πολλαὶ ἀπ᾿ αὐτοῦ πεποίηνται, αἱ μὲν ἀέναοι, ἀφ᾿ ὧν ὑδρεύονται οἱ παρ᾿ ἑκάτερα ᾠκισμένοι, τὰς δὲ καὶ πρὸς καιρὸν ποιοῦνται, ὁπότε σφίσιν ὕδατος ἐνδεῶς ἔχοι, ἐς τὸ ἐπάρδειν τὴν χώραν· οὐ γὰρ ὕεται τὸ πολὺ ἡ γῆ αὕτη ἐξ οὐρανοῦ· καὶ οὕτως ἐς οὐ πολὺ ὕδωρ ὁ Εὐφράτης τελευτῶν καὶ τεναγῶδες [ἐς] τοῦτο οὕτως ἀποπαύεται. // (3) Now of these rivers Euphrates and Tigris, which enclose Assyria between them — hence the name Mesopotamia (‘between-rivers land’) — the Tigris, which runs through much lower ground, receives many canals from the Euphrates, and takes in many tributaries, thus increasing its volume, runs into the Persian ocean and is large and cannot be crossed at any point down to its mouth, since none of the water is used up on the land. For the land is here higher (4) than the river, and the Tigris does not empty its water into canals or into any other river, but instead receives theirs; hence it does not provide irrigation for the land. The bed in which the Euphrates flows (5) is, however, higher; its banks are level with the land at all points, and many canals have been cut from it, some of which are always running and supply water to the inhabitants on either bank, while others are constructed as occasion requires, whenever they are short of water to irrigate the land; for in general this country gets no rain. Thus the Euphrates, coming to an end in little water, and that swampy, ceases to flow.” Back to text

- Note 4: for an English translation, see Mc Crindle 1876 Indica; Greek text available online on Perseus at this link; an online English translation is available here. Back to text

- Note 5: “6.3. Fitzmyer’s rendering of XXI, 24 BYN NHRYN, ‘between the two rivers’, is open to question on two grounds.

Firstly, if the phrase is intended as appellative, as interpreted by him, one cannot see why ‘the two rivers’ is expressed by a noun in status absolutus, and not by BYN NHRWTߴ (or NHRYߴ). Therefore, it is preferably a place name, so that one should translate it Ben Naharyn or Mesopotamia.

Secondly, Fitzmyer tacitly presupposes that NHRYN is a dual form realized as /nahrēn/ or /nahrain/, the reference of course being to Tigris and Euphrates. This presupposition however is hard to maintain for a number of reasons. (1) The Semitic dual morpheme is, except for Arabic, semantically restricted to nouns indicating objects which go in pair and a few numerals. Our case dres not belong to such categories. (2) Even among this delimited group of nouns the morpheme is on the way of disappearance: in Syriac, for instance, it is preserved only in tərən (f. tartēn) ‘two’ and māߴṯēn ‘two hundred’. (3) The traditional concept of Mesopotamia ‘between the two rivers’ is the result of a later secondary development. Finkelstein has justly called attention to the remarkable fact that the Akkadian form, which was later translated into Aramaic and other languages, including Greek, is significantly bīrit nāri(m) with ‘river’ in the singular. These considerations make it more likely that one has here a plural form.” Back to text - Note 6: see Finkelstein 1955 Subartu, pp. 3, 7 and fn. 68. Back to text

Back to top: “Mesopotamia”