|

“Monotheism may be our particular spice, but the dish is universal” Amos Oz and Fania Oz-Salzberger 2012, Jews and Words, Yale: Yale University Press [ISBN: 9780300205848], p. 86. |

NB: on this page, the abbreviation “ANE” stands for “Ancient Near East”.

Back to top: Rituals in the Ancient Near East and Israel

1. General Introduction

This theme focuses on the discussion on rituals and cultic activities which characterize the worshipping of G/god(s) in the Ancient Near EastNote 1 and Israel.

A specific section of this page will be focusing on some peculiar cultic ritual performed at Ebla/Tell Mardikh, also involving the deification of royal ancestors.

Reference to biblical passages can be easily found on page Biblical passages, offering the original text (Hebrew/Greek) and an English translation.

Back to top: Rituals in the Ancient Near East and Israel

2. Giorgio Buccellati’s view

Giorgio Buccellati investigates the topic of rituals in Ancient Near East and Israel under a structural comparison, specifically in two chapters of his book “When on High the Heavens…”: chapter 18, on magic and rituals for the individual, and chapter 22, on cults performed at an institutional level.

The “bi-polarity” of the discussion on rituals (considered as both referring to an individual and an institutional level) is clearly exemplified in the following table (from Giorgio Buccellati’s book, chapter 7, section 2: Table of Contents*):

I briefly report here some considerations taken from passages from these two chapers, useful at better defining Giorgio Buccellati’s structural comparison (links address directly to Excerpts/Buccellati2021When).

Back to top: Rituals in the Ancient Near East and Israel

2.1 Chapter 13: Magic and rituals for the individual

See Excerpts/Buccellati2021When/Magic and rituals for the individual.

- Nature and function of rituals*: Rituals are institutionalized channels to establish a connection with the absolute [see Excerpts/Buccellati2021When/Rituals 1].

- Ritual vs. ritualism = formalism: Rituals are not mechanical repetition of rules but they disclose a spiritual content [see Excerpts/Buccellati2021When/Rituals 2].

- Occasions for rituals (their context): rituals are particularly effective in specific steps of human life: birth*, sexual maturity, psychological and physical crises (like an illness), death [see Excerpts/Buccellati2021When/Rituals 3].

- Similarities and differences between ANE and Israel: uni-directional vs. bi-directional way of sacrifices (Mesopotamian gods are passive; Israel's God is active) [see Excerpts/Buccellati2021When/Rituals 4].

- ANE: gods' need for sacrifices (+)* Note 2: Mesopotamian gods require sacrifices because they need them [see Excerpts/Buccellati2021When/Rituals 5].

- Israel: God does not need sacrifice(s) (-): Israel's God requires sacrifices but does not need them [see Excerpts/Buccellati2021When/Rituals 6].

This idea is made even more evident by a comparison between some passages from the Mesopotamian Dialogue of Pessimism (cf. chapter 12, section 3) and other biblical sources:

| DP, 133-142 [Lambert 1960] |

133 bi-i-ta lu-ud-di [...] 134 bi-šá-a a-a aḫ-ši-iḫ [...] 135 pí-il-lu-de-e ili li-meš par-ṣ[i lu-ka]b-⸢bi⸣i[s] 136 bé-e-ra lu-na-ak-kis li- × × × ⸢×⸣ ak-lu 137 bi-ir-ta lu-ul-lik ni-⸢sa-a-ti lu⸣-ḫu-uz 138 bé-e-ra lu-up-ti ⸢a⸣-g[a-a] lu-maš-šèr 139 bé-e-ra ki-di <šar>-ra-qiš [lu-u]r-tap-pu-ud 140 bi-it-bi-ti-iš lu-ter-ru-ba ⸢lu-ni⸣-ߴi bu-bu-ti 141 bi-ri-iš lu-ut-te-ߴe-lu-ma su-le-e lu-ṣa-a[-a-ad] 142 pí-iz-nu-qiš ana qir-bi lu-t[er ...] |

133 I will leave my house [...] 134 I'll throw away what I own [...] 135 I'll forget religion, and I'll trample on divine worship, I'll just kill a calf, yes, but only to eat it, and then 136 I'll go away to faraway countries. 137 I'll dig a well to drink from it, 138 I'll wander like a thief, away from everything. 139 I'll go from house to house to keep hunger away, 140 and even if I'm hungry I'll keep wandering, comfortable only in the streets. 141 Reduced to being a beggar, I'll look inside, 142 because happiness is far, far away [...]. |

| 1 Sam 15:22 | הִנֵּ֤ה שְׁמֹ֙עַ֙ מִזֶּ֣בַח טֹ֔וב לְהַקְשִׁ֖יב מֵחֵ֥לֶב אֵילִֽים |

Obedience is better than sacrifice. |

| Ps 40:6 |

רַבֹּ֤ות עָשִׂ֨יתָ׀ אַתָּ֤ה׀ יְהוָ֣ה אֱלֹהַי֘ נִֽפְלְאֹתֶ֥יךָ וּמַחְשְׁבֹתֶ֗יךָ |

You do not want sacrifice or oblation, you have opened my ear instead. |

| Hos 6:6 |

כִּ֛י חֶ֥סֶד חָפַ֖צְתִּי וְלֹא־זָ֑בַח וְדַ֥עַת אֱלֹהִ֖ים מֵעֹלֹֽות |

I want love, not sacrifice; knowledge of God, not holocaust. |

- Restoration of order: to re-establish a relationship with the absolute, a restoration of order is needed [see Excerpts/Buccellati2021When/Rituals 7].

- ANE: restoration in ANE is achieved by applyiing specific ritual rules [see Excerpts/Buccellati2021When/Rituals 8].

- Israel: restoration in Israel is a gift of God [see Excerpts/Buccellati2021When/Rituals 9].

- Contexts for rituals*: there are great moments of transition in human life [see Excerpts/Buccellati2021When/Rituals 10].

- The initial confirmation of order occurs at the birth of the individual. While we know of no particular ceremonies related to this event in Mesopotamia, biblical circumcision [see infra] is proposed as a form of consecration to God of the individual (male) at the beginning of his existence.

- ANE: none (-): no rituals for newborn in ANE [see Excerpts/Buccellati2021When/Rituals 11].

- Israel: circumcision (+): in Israel, circumcision is a specific sign in human life, directly required by God [see Excerpts/Buccellati2021When/Rituals 12].

- Sexual maturity is like a second birth, which leads to the formation of human couples and the consequent formation of the family.

- ANE: ritual prostitution (+).

- Israel: none (-).

- The supreme laceration of order is death.

- ANE: funerary meals and after death rituals (+).

- Israel: none (apart from funerals) (-).

- Ritualism and a degradation of the experience: when rules are only mechanically applied, with no entanglement with the absolute, rituals become ritualism (i.e. a formalism of a sincere religious practice) [see Excerpts/Buccellati2021When/Rituals 13].

- ritualism/formalism;

- fanaticism;

- fatalism.

Back to top: Rituals in the Ancient Near East and Israel

2.2 Chapter 22: Worship

See Excerpts/Buccellati2021When/Institutionalized worship.

- Divinity – object or subject?: the relationship with the absolute depends on the very nature of the divine entity [see Excerpts/Buccellati2021When/Worship 1].

- ANE: object: in ANE the gods are passive entities (see e.g. the Mesopotamian concept of "service" (dullu)*Note) [see Excerpts/Buccellati2021When/Worship 2].

- Israel: subject: in Israel God is an active presence (cf. the concept of shekinah) who requires a different kind of 'service' (עֲבוֹדָה, `ăbodā(h)) [see Excerpts/Buccellati2021When/Worship 3].

- Sacrifice*: the function and meaning of sacrifices exemplifies such a dichotomy [see Excerpts/Buccellati2021When/Worship 4]:

- ANE: need for (+): in ANE the sacrifice is meaningful in itself.

- Israel: no need for (-): God does not need sacrifices [cf. also Table 1 supra], since he is the creator (the ethos of creation* is fundamental in Buccellati's view), but it is considered as a recognition of God's preminence as creator of everything.

- Priests = technicians of the cult*: priests in ANE are technicians of the cult [see Excerpts/Buccellati2021When/Worship 5].

- Sacralization*: sacralization consists in the regolamentation of phenomena through some specific forms of control* [see Excerpts/Buccellati2021When/Worship 6].

- Control of time*: one of this forms of control consists in the regolamentation of time represented by the creation of calendars* (for Israel, see e.g. the Talmudic treaty Rosh ha-Shanah, on the New Year's Day(s) and the major festivals) [see Excerpts/Buccellati2021When/Worship 7].

- ANE: the New Year fest (akītu)*: in Mesopotamia the New Year Fest is a fundamental event [see Excerpts/Buccellati2021When/Worship 8].

- Israel: the ethos of creation*: also in Israel calendars are important but each time is always reconnected and anchored to the creation [see Excerpts/Buccellati2021When/Worship 9].

- Space: space is important in determining moments of direct contact between the divine entity and the people [see Excerpts/Buccellati2021When/Worship 10].

- ANE: processions (+): in ANE this occasion of encounter of the believers with the gods is represented by the solemn processions.

- Israel: no processions (-) (but cf. *): in Israel, the aniconicity of God excludes any direct contact with God; everything is reconnected to the ethos of creation*.

- Death and Underworld [see Excerpts/Buccellati2021When/Worship 11]:

- ANE: rituals (+): in ANE specifical rituals are performed on the occasion of human death.

- Israel: no rituals (-): in Israel there are not specific ritual for the dead, apart from mourning and burial rites. Even if the concept of afterfife is quite similar in ANE and Israel, there are, however, three important differences:

- the absence of sacrifices and rituals for the dead after burial.

- Apart from the case of necromancyNote 3 (1 Sam 28,8-20; Is 8,19), there are no references to the spirits of the dead.

- Above all, one notes the lack of a description of the ideal of life protracted in time.

Back to top: Rituals in the Ancient Near East and Israel

3. Rituals in the Ancient Near East

A useful source for information about rituals and cultic activities in the ANE can be found in the following publication:

Michael P. Streck (ed. in chief),

Reallexikon der Assyriologie und Vorderasiatischen Archäologie,

Berlin, New York: Walter de Gruyter; Vol. 11 [Prinz, Prinzessin - Samug].

I report here a brief summary with a description of some excerpts from the lemma Ritual (pp. 421-438, by Walter Sallaberger and Volker Haas: “Rituals in Mesopotamia” and “Rituals in the Hittite culture”)Note 4 [English translation from German by M. De Pietri], highlightening some peculiarities in rituals and cultic system of the ANE (the full text of the excerpt can be found at Excerpts/RlA; online version):

Back to top: Rituals in the Ancient Near East and Israel

A: “Rituals in Mesopotamia”

(Full text of the excerpt at Excerpts/RlA/Rituals in Mesopotamia)

- General: ritual is a common definition referring to all aspects of a specific cultic actitivy [see Excerpts/RlA/Rituals ANE 1].

- Sources:

- General sources: relatively few sources are preserved (less about the temple cult*, differently from the Old Testament) [see Excerpts/RlA/Rituals ANE 2].

- Myths and rituals: on many occasions, there are strict connections between ritual activities and mythological texts (e.g. for the Babylonian New Year fest [akītu]*) [see Excerpts/RlA/Rituals ANE 3].

- Elements of ritual: rituals are composed of many complex elements [see Excerpts/RlA/Rituals ANE 4].

- Occasions: specific occasions for rituals can be retraced, mostly connected to determined moments in human life [see Excerpts/RlA/Rituals ANE 5].

- Ritual texts:

- General: ritual texts describes many features of a rite (e.g. the actors, the sequence of actions, the time, the place. etc.) [see Excerpts/RlA/Rituals ANE 6].

- Historical overviewNote 5:

- Ebla

- Early Dinastic Mesopotamia

- Old Babylonian period

- Late Bronze Age Syria and Anatolia

- Assur

- Babylon (1st millennium BC)

- Literary tradition between 2nd and 1st millennium BC

Back to top: Rituals in the Ancient Near East and Israel

B: “Rituals in the Hittite culture”Note 6

- Terminology

- Origin and development

- The festive rituals

- The actors

- The festival community

- The function of the festive rituals

- Ritual elements

- The purullija-New Year festive ritual (cf. *)

- The KI.LAM festive ritual

- The AN.DAḪ.ŠUM festive ritual

- The nuntarrijašḫa festive ritual

- The monthly festive ritual

- Rituals on the occasion of extraordinary natural events

- Rituals on special occasions at court

- Private festive rituals

- Incantation rituals

- Client rituals

- Mythologems or historiolae

- The ritual of the AZU-priest

- The ritual of the ŠU.GI-woman

- Rituals of the hierodules

- Rituals of the augurs (lù.mešMUŠEN.DÙ)

- Rituals for the army

- Profane rituals

- Rituals for 'common people'

Back to top: Rituals in the Ancient Near East and Israel

4. Worshipping God in ancient Israel

A useful source for information about rituals and cultic activities in ancient Israel can be found in the following handbook:

Paul Achtemeier et al. 1996,

The HarperCollins Bible Dictionary,

San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco.

I report here a brief description of some excerpts from the lemma Worship (pp. 1222-1225)Note 7 (the full text of the excerpts can be found at Excerpts/Achtemeier1996Harper):

- WorshipNote 8: the actitude of reverence to a deity, involving the concept of "service"* in the temple, performing many ritual aspects (inclusing sacrifices*); sometimes worship is offered to God as king* [see Excerpts/Achtemeier1996Harper/Worship].

- SacrificeNote 9: sacrifice* is the most prominent feature of worshipping (maybe derived from earlier forms of "tributes"Note 10); the most important sacrifice was that performed on the Day of the Atonement* or thanksgiving: the purpose of this sacrifice was not to atone for any kind of sin, as the name seems to imply. Crimes against other people were dealt with by appropriate punishments that did not involve sacrifice, while deliberate crimes against God (done "with a high hand"*) could not be sacrificially atoned for at all [see Excerpts/Achtemeier1996Harper/Sacrifice].

- Temple* RitualNote 11: the daily temple ritual is precisely determined by fixed rules [see Excerpts/Achtemeier1996Harper/Temple Ritual].

- Donations: In addition to these public and private sacrifices, offered at regular seasons or at will, the people donated a tenth portion of their produce to the sanctuary. Furthermore, the priests received the first fruits* of all produce [see Excerpts/Achtemeier1996Harper/Donations].

- Ritual PurityNote 12: Persons participating in worship had to be ritually clean* [see Excerpts/Achtemeier1996Harper/Ritual Purity].

- Other Versions of Ritual Procedures: The book of Deuteronomy presents a slightly modified (though much less detailed) version of the system described by the Priestly textsNote 13. The principal difference lies in Deuteronomy's insistence on a single sanctuary for the entire land of Israel to which all sacrifices were to be brought [see Excerpts/Achtemeier1996Harper/Other Versions].

Back to top: Rituals in the Ancient Near East and Israel

5. Comparison between Ancient Near East and Israel

Another very useful book to gain information about rituals and cultic activities in ANE and Israel (as specifically attested in the OT) is represented by the following handbook:

Samuel E. Balentine (ed.) 2020,

The Oxford Handbook of Ritual and Worship in the Hebrew Bible,

Oxford: Oxford University Press.

I report here a brief description of some excerpts from this book, outlining some topics relevant to the present theme (the full text of the excerpts can be found at Excerpts/Balentine2020Ritual).

First of all, some methodological considerations are here pinpointed (from Chapter 8. Rituals and Ritual Theory: A Methodological Essay [by Ithamar Gruenwald]; remarkable key-words are bolded) [comments are displayed in square brakets “[…]” and smaller font after each quotation; references to aformentioned passages of Giorgio Buccellati’s view or ANE/Israel rituals are hyperlinked with *]:

- What is a ritual?: ritual is considered as a "riddle", difficult to be understood (even by ancient people), whose aim is basically the achievement of (a) certain goal(s). They need to be based on an accepted authority and on a working coherence [see Excerpts/Balentine2020Ritual/Definition of Rituals].

- Nature of rituals: rituals consist of stylized and repetitive protocols (which can be comapared to Buccellati's "patterns" [see Excerpts/Balentine2020Ritual/Nature of Rituals].

- Function of rituals: rituals are basically a major component of human behavior [see Excerpts/Balentine2020Ritual/Function of Rituals (1)].

- Analysis of rituals: rituals has to be analyzed under the lens of behavioral factors which imply specific anthropological functions [see Excerpts/Balentine2020Ritual/Analysis of Rituals].

- Analysis: methodology (two ways): rituals can be either observed (from the outside) or analyzed (from the inside) [see Excerpts/Balentine2020Ritual/Methodology of Analysis].

- Behavioral view: rituals are extensions of the human mind, thus to be analyzed under a behavioral angle [see Excerpts/Balentine2020Ritual/Behavioral View].

[Note how here the dichotomy "individual vs. group" recalls G. Buccellati's distinction between and "individual vs. a communal level" (Chapters 13 and 22 respectively)*.] - Myths and rituals: rituals are sometimes justified by or reconnected to mythic contexts [see Excerpts/Balentine2020Ritual/Myths and Rituals].

- Function of rituals in the community: rituals shared by a community are a hierarchy and social stratification [see Excerpts/Balentine2020Ritual/Function of Rituals (2)].

- Brief synthesis: rituals are characterized by segmentation into segmented units which form a ritual Gestalt and aim at prevent the termination, disintegration, or annihilation of the "cosmos" [see Excerpts/Balentine2020Ritual/Synthesis on Rituals].

- "Four-steps" structure of ritual (segmentation): basic structure of a ritual: 1) analysis of the reality; 2) performing a ritual act; 3) a determined effect is achieved; 4) detrmination of results or consequences of the ritual [see Excerpts/Balentine2020Ritual/Segmentation of Rituals].

Hereafter, some considerations on some aspects concerning Giorgio Buccellati’s volume are presented, and structural comparisons are advanced, quoting passages from the aformentioned book:

- Meaning of rituals*: rituals are for human beings a channel to the transcendent [see Excerpts/Balentine2020Ritual/Meaning of Rituals].

- "Scapegoat" rituals in Hittite culture*: the "scapegoat" or substitute ritual is shared by both the ANE (specifically Hittite) and Israel's religious and ritual tradition [see Excerpts/Balentine2020Ritual/"Scapegoat" Ritual].

- Relationships between Israel and Canaanite rituals*: a connection of certain Israelite rituals to earlier Canaanite practices can be advanced [see Excerpts/Balentine2020Ritual/Relationships between Israel and Canaanite Rituals]. [cf. infra the section on Cultic Rituals at Ebla/Tell Mardikh, where also a comparison to Ugaritic texts is presented.]

- Atonement in Syria*: on the one hand, the atonement ritual is shared by Israel and other Syrian traditions (e.g. Ugarit) [see Excerpts/Balentine2020Ritual/Atonement in Syria].

- Palace rituals in Syria: on the other hand, palace rituals are not so common in Israel, at least as they are in the other Syrian realities [see Excerpts/Balentine2020Ritual/Palace Rituals in Syria].

- Priests*: each religious system has his own specific cult personnel [see Excerpts/Balentine2020Ritual/Priests].

- Worship ritual*: worship rituals in Israel are basically focused on sacrifices and rituals of purity connected to the service in the Temple. Rite of separation (a kind of transitional rite during which the person is in a "liminal" state) are performed to establish a particular status to the cult technicians [see Excerpts/Balentine2020Ritual/Worship Ritual].

[This passage is very interesting since many topics presented by Giorgio Buccellati are here recalled: the ethos od creation*, the concept of "rite of passage"*, and that of "sacralization"*.Note 14] - Anthropology of rituals: under an anthropological view, rituals can be considered as "representational", i.e., they stand representatively for various human phaenomena [see Excerpts/Balentine2020Ritual/Anthropology of Rituals].

- Comparative approach (ANE, Israel and Greece): hereafter, some common (or diverging) features of ancient Mediterranean religious approaches to rituals are pointed out (even by widering the geographical spectrum also to Egypt and the Aegean). It is interesting to note that in this comaparative analysis, the authors apply both an emic and an eticNote 15 approach [see Excerpts/Balentine2020Ritual/Comparative Approach].

- G/god(s):

- Mesopotamia: in ANE gods are predominantly personalized entities [see Excerpts/Balentine2020Ritual/G/god(s)/Mesopotamia].

- Egypt: similar to the ANE; [passage not reported here: see Hartenstein, pp. 146-147.].

- Syria (Ugarit): at Ugarit, gods are basically described according to the pattern of court and family structures (family metaphor) [see Excerpts/Balentine2020Ritual/G/god(s)/Syria].

- Hittite: Hittite gods present a mix of specific local and autochtonous character, with influence of substratum from the Hurrian culture (mostly from a certain perion, in between the so-called Old Kingdom and the Hittite Empire, given the influence on the royal court of traditions coming from Kizzuwatna); there is also, in de determination of gods' features, a quite important stress on the concept of "purity" [see Excerpts/Balentine2020Ritual/G/god(s)/Hittite].

- Greece: some similarities to ANE even if the origin of Greek gods is basically Indo-European and not Semitic; [passage not reported here: see Hartenstein, p. 148.].

- Phoenicia: in Phoenicia, aside the anthropomorphic shape of gods, also aniconic symbols are attested and worshipped [see Excerpts/Balentine2020Ritual/G/god(s)/Phoenicia].

- Temple Service:

- Mesopotamia: the temple service in Mesopotamia is basically addressed to "feed" the gods (through their cultic statues); the daily cult in Babylonian temples was aligned with the idea of a "service"* [see Excerpts/Balentine2020Ritual/Temple Service]

- Egypt: similarities to ANE; [passage not reported here: see Hartenstein, pp. 152-153.].

- Sacrifice*:

- Mesopotamia: sacrifices main the connection between humans and gods; nevertheless, also prayers and invocations were also important [see Excerpts/Balentine2020Ritual/Sacrifice/Mesopotamia].

- Israel: sacrifice is not intended to "feed" God (who, being the creator, does not need for it); sacrifice is a "gift" to God, a deprivation of something important dedicated (consacrated) to God. In Israel, the symbolism of feasts and "hospitality" connected to sacrifices is also noteworthy [see Excerpts/Balentine2020Ritual/Sacrifice/Israel].

- The Temple: in a world were diseases, childbirth*, or natural phaenomena could struggle human life, in ANE temples fulfilled the aim of concretizing the divine presence, giving a sort of "control"* over those phaenomena, thank to the action of (a) god(s) present in the temple shrines (something similar can be seen in Israel with the concept of shekinah, i.e. the physical presence of God in the Sanctuary. In general, the temple is considered as the house of G/god (see e.g. some words for "temple": Ugaritic and Aramaic bt, Hebrew and Aramaic byt, Akkadian bītu, Sumerian é, Hittite per- and parn-, and Egyptian ḥwt and pr)Note 16 [see Excerpts/Balentine2020Ritual/Temple].

- Ritual experts*: in ANE there are many ritual experts, acting as mediators between gods and human beings. A similar differentiation in cultic responsabilities can be also seen in Israel [see Excerpts/Balentine2020Ritual/Ritual Experts].

- Mesopotamia: priests in Mesopotamia are servants of gods (as sometimes also the king is). Priests are performers of cultic activities and play a specific role during feasts, such as the New Year Festival*, but they are also keeper of knowledge and traditions [see Excerpts/Balentine2020Ritual/Ritual Experts/Mesopotamia].

- Mari (Euphrates): priests at Mari are sometimes described with a terminology similar to that of Mesopotamia; nevertheless, they cannot be perfectly equated with the Mesopotamian priests. Also priestesses of a high rank (nin-dingir[-ra]Note 17) are attested [see Excerpts/Balentine2020Ritual/Ritual Experts/Mari].

- Hittite Anatolia: the cult is strongly organized by the royal court [see Excerpts/Balentine2020Ritual/Ritual Experts/Hittite].

- Egypt: some features are similar to ANE: [passage not reported here: see Hartenstein, pp. 152-153.].

- Israel (Bible):

- Priests: in Israel, cultic responsabilities are divided and assigned to different figures, mostly the "priest," kohēn, with many tasks. A great importance is given to the High Priest which is sometimes appointed after he had confessed his sins over the head of a living goat, which is sent into the wilderness (the scapegoat*). The role of the priests can be summarized with the terms "mediator" and "representative". Also the profets and the Levites have specific cultic responsabilities (or they in any case involved in rituals) [see Excerpts/Balentine2020Ritual/Ritual Experts/Israel].

- Sacred and rituals times*: ritual times and festival occasions were precisely determined, both in ANE (sometimes connecting festivals to specific myths, such as the Enuma Elish*, recited at the annual Babylonian Akitu (New Year's) Festival*) and in Israel, where worship basically follows a calendar whose units of time were established at creationNote 18 [see Excerpts/Balentine2020Ritual/Sacred and Rituals Times].

- Ritual objects: many ritual objects are attested and carefully describe in the Old Testament. Some scholars have suggested that any connection between rituals (and so, ritual objects) was the result of Canaanite influence* [see Excerpts/Balentine2020Ritual/Ritual Objects].

- Cultic statues: while in ANE cultic statues, consacreted with specific ceremonies such as the "washing of the mouth" (mīs pī) or the "opening of the mouth" (pīt pī)Note 14, represented the physical presence of a god in the temple, in Israel all the statues were regarded as "idols" [see Excerpts/Balentine2020Ritual/Cultic Statues].

- Ritual practices: many ritual practices are attested both in ANE and Israel [see Excerpts/Balentine2020Ritual/Ritual Practices].

- ANE: in ANE, ritual practices aimed at maintaining relationship with the gods, and where intended to give them gifts, and carry out performances for* Note 2 them [see Excerpts/Balentine2020Ritual/Ritual Practices/ANE].

- Israel: in Israel, God is the only referent of any ritual action [see Excerpts/Balentine2020Ritual/Ritual Practices/Israel].

- Prayer: in the Hebrew Bible, prayer could be directed to God at his sanctuary/temple [see Excerpts/Balentine2020Ritual/Prayer].

- Sacrificial rituals: sacrifices are cultic actions transferring materials to deities, sometimes intended as formal presentation of an offeringNote 19. Many offerings of food are described in ANE texts, such as (for the Hittites) the "Instructions to Priests and Temple Officials"Note 20 [see Excerpts/Balentine2020Ritual/Sacrificial Rituals].

- Non-sacrificial ritual activities: also non-sacrificial ritual activities are attested [see Excerpts/Balentine2020Ritual/Non-sacrificial Rituals].

- Purification and Elimination: purification from sins, sometimes based on water, are attested in many ANE cultures (see e.g. the Hittite "Instructions to Priests and Temple Officials"Note 20, or the the Day of Atonement* in Israel, or the New Year Festival of Spring* at Babylon [see Excerpts/Balentine2020Ritual/Purification].

- Performance, Procession, and Lifestyle: ritual processions were common in ANE*, while they are practically absent in Israel (only, at least during the period of peregrination of YHWH's ark of the covenant to Jerusalem). Musicians, singer, and performers are known both in Israel and in ANE (e.g. during the magnificent cultic parade of the Babylonian New Year Festival*). Hittite cultic processions are often depicted on vases or on city orthostatsNote 21 [see Excerpts/Balentine2020Ritual/Performance].

- Ritual Speech and Reciting: ritual speeches and public recitings (along with spells and incantations) are attested in both Israel and ANE (e.g. during the Babylonian New Year Festival*, the high priest was to recite the Enuma Elish* to the god Marduk). Unlike the Babylonian recitation (addressed only to the god and probably in a private form), in Israel readings were public and the audience was human [see Excerpts/Balentine2020Ritual/Ritual Speech].

- Divination and Magic: while in ANE practices like magic and divination were quite common and widespread, in Israel, because of the monotheistic nature of the religion, such activities were banned (they were in somehow accepted only when directly addressed to God, i.e. YHWH, such as the case of the Urim and Thummim)Note 22 [see Excerpts/Balentine2020Ritual/Divination and Magic].

- Ritual gestures: ritual gestures are of course attested both in ANE and Israel and are sometimes well described in ancient sources (such as the case of the Hittite "Instructions"Note 20 or the books of Leviticus and Deuteronomy in the Torah). Common and shared gestures or ritual practices were e.g. the gesture of raising the hands*, or the gestures of anointing* Note 23 [see Excerpts/Balentine2020Ritual/Ritual Gestures].

- Function of rituals: rituals had many purposes in both ANE and Israel [see Excerpts/Balentine2020Ritual/Function of Rituals (3)].

- Integral part of existence: 1) rituals were an integral part of human beings' existence [see Excerpts/Balentine2020Ritual/Integral Part of the Existence].

- Vehicle for complex concepts: 2) rituals were a simple way to vehicle complex ideas and concepts (in so-called "pre-philosophical" societies) [see Excerpts/Balentine2020Ritual/Vehicle for Complex Concepts].

- Medium of worship: 3) rituals, as "medium of worship", had also the goal of creating or building a community, shaped through shared practices which also re-activated communal believes and thoughts (mnemonic function of rituals) [see Excerpts/Balentine2020Ritual/Medium of Worship].

Back to top: Rituals in the Ancient Near East and Israel

6. Cultic Rituals at Ebla/Tell Mardikh

Location of Ebla/Tell Mardikh (from Google Earth)

Aerial view of Ebla/Tell Mardikh (from SAGAS)

This section is dedicated to the discussion on some papers already entered in the Bibliography and in Critical Reviews which all deal with ritual activities performed at Ebla/Tell Mardikh and Ugarit/Ras Shamra, specifically:

- Bonechi 1989

[Bibliography] [Review] - Matthiae 2012

[Bibliography] [Review] - Viganò 1995

[Bibliography] [Review] - Viganò 2000

[Bibliography] [Review]

This papers well exemplify some peculiar aspects of ANE rituals and are here considered as a apecimen of ANE cultic activities, with a specific focus on the Syrian area (and mainly Ebla/Tell Mardikh and Ugarit/Ras Shamra).

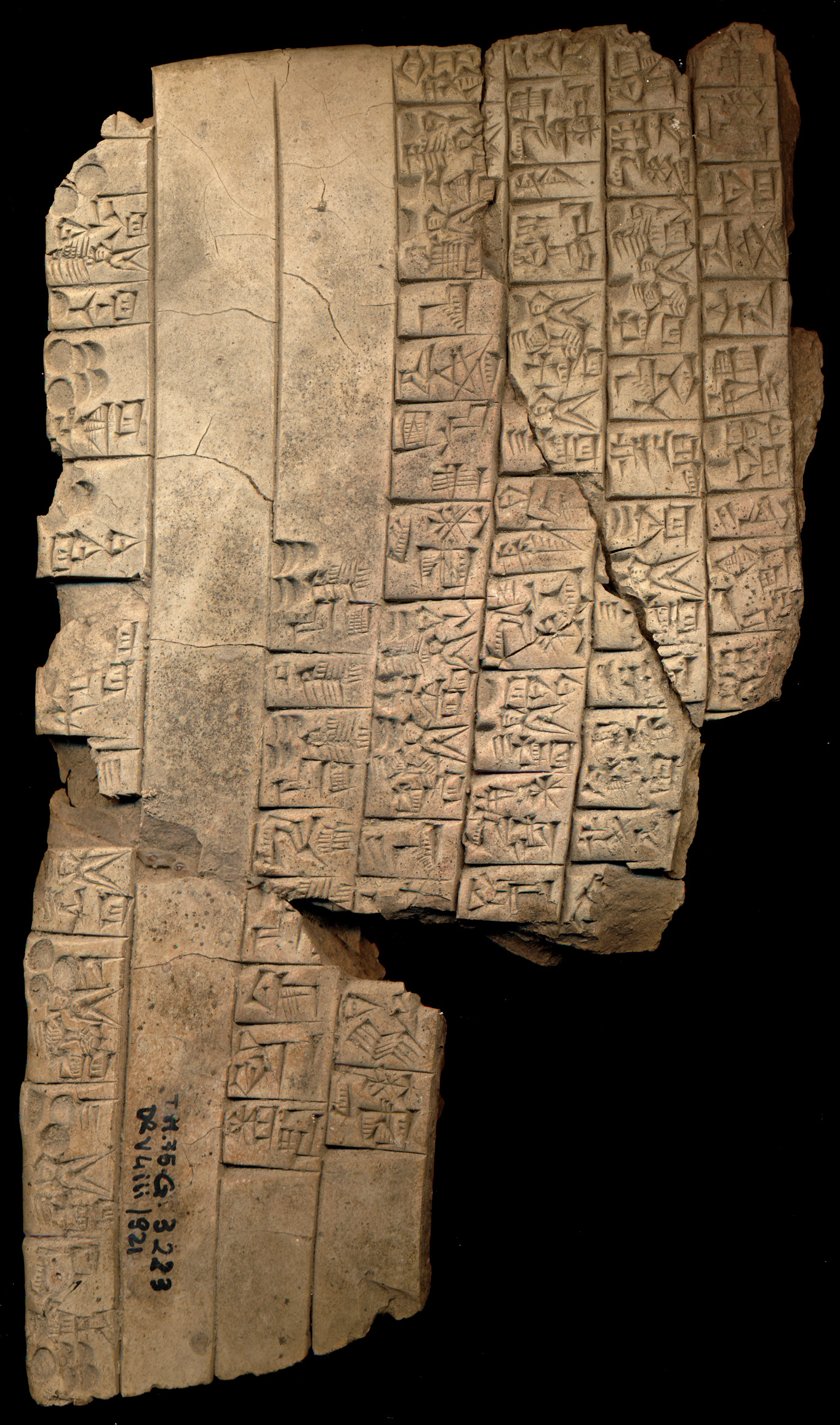

Document ARET 3.192 from Ebla/Tell Mardikh (after CDLI)

A first element of Syrian cultic activities is stressed by the first contribution (Bonechi 1989), i.e. how through the reading and analysis of written sources we can reconstruct many specific features of cultic activities performed at Ebla/Tell Mardikh, which included specific priests (and other cultic technicians), prayers and cultic actions, determined worshipped gods, and a fixed ritual terminology.

Four key elements can be generally noticed:

- the presence of specific priests, considered as 'cultic technicians';

- the recurring of determined offerings to the polyad god dKura;

- the use of ritual terms such as syntagma DU11.GA, 'order, vow', 'request' and KA.GÁ.II = ragāmum = bâlum, 'recited prayer';

- the attestation of another ritual figure, expressed by the term da-mi-mu, 'reciter, lamenter'.

All in all: “The value that these elements assume is based on the meaning of some keywords, as indicated by Ebla’s lexical lists, both on the basis of prosopographic analysis, suggests the identification of an act of worship” (p. 131; English translation from the original Italian version by M. De Pietri).

Throughout the article, the author presents many texts from Ebla (such as e.g. ARET 3.192, in the picture above), sketching a relative chronology of the examined terminology and investigating the diachronic development of the rituals at Ebla/Tell Mardikh.

Relief from the side part of a cult basin made of basalt (detail). Found at Ebla/Tell Mardikh, Tempel B1 (from AKG-IMAGES)

A second characteristic element of Syrian cultic activities involved the possibility of a cult addressed to deified kings or, more generally, to royal ancestors.

This topic is investigated in Matthiae 2012. The author goes across archaeological and textual evidence from Ebla/Tell Mardikh, aiming at reconstructing some specific ritual dynamics related to the cult of the royal ancestors (the Rapiʼuma or Rephaʼim of the texts from Ugarit/Ras Shamra), spanning the Ancient Bronze IVA (ca. 2400-2300 BC) to Iron Age II (ca. 900-720 BC).

The BA IVA texts found in the Royal Archives of Ebla (Royal Palace G) mention the deification of the dead kings and the cult offered to the royal ancestors: the ‘Ritual of the Regality’ (found in L. 2769, ca. 2350-2300 BC), and other documents describe celebrations involving a procession of the royal couple to the sites of Binash and Darib/Atareb(?) (two royal necropoles), presenting offerings to the royal ancestors.

Rituals and offerings addressed to royal cults in Ebla/Tell Mardikh are also attested: in fact, administrative texts quote offerings presented in the Royal Palace to the DINDIR EN (‘the god of the lord/king’), to the DINGIR maliktum (‘the god of the queen’), or to the DINGIR a-mu (‘the god of the father’).

Furthermore, some banquet scenes attested on the wall of royal hypogea have been interpreted as ritual banquets (such as the kispum) described in contemporary Ugaritic texts of the Late Bronze Age II.

Eventually, the structure of the Sanctuary B2 (MB II, ca. 1800-1600 BC), discovered in the lower city of Ebla/Tell Mardikh, shows a peculiar architecture including a wide room clearly adhibited to ritual banquets (maybe similar to the North-West Semitic marzeah (see e.g. King 1989 or to the Mesopotamian kispum (see e.g. Mac Dougal 2014) with many participants. These banquets were performed on the occasion of the death of the reigning king, to guarantee him the assumption among the ancestors.

This hypothesis is strengthened by a steatite cylindrical seal (Erlenmeyer Collection; Paleo-Assyrian period, unknown provenance but possibly from Ebla/Tell Mardikh) depicts three scenes involving gods of Yamkhad and the rapiʼuma of Halab, probably on the occasion of the death of a Syrian king.

In short: “The tradition of deification of deceased kings and the faith in an essential protection provided by these deified beings to the community of the living, the reigning house, and the whole society, go back, in Syria, to the very beginning of urban life, in Proto-Syrian times and in the sudden growth of Ebla at the acme of the ‘second urbanization’, shortly after the middle of the third millennium BC, when the rituals of the Royal Archives testify to the role of the deified dead kings in the renewal of the reigning kings” (p. 991 [Italian version]; English translation from the original Italian version by M. De Pietri).

[Note that the hypothesis of deification of kings at Ebla has not been considered in Giorgio Buccellati’s volume (where the author admits only “sporadic evidence of attempts to deify kings”; see full excerpt at Excerpts/Buccellati2021When/Spirits of the dead/Deification of kings) since the present paper by P. Matthiae has been published when Buccellati’s Quando in alto… went to print].

Ebla/Tell Mardikh,Archives of the Royal Palace G (from Ebla Website [© Ebla.it])

A third peculiar element of Syrian cultic activities involves some purification rituals and rituals of regular offerings.

This feature is deeply investigated in Viganò 1995: here, the author presents a discussion on some ritualsNote 24 attested in documents from the Archives of the Royal Palace G at Ebla/Tell Mardikh: the Purification Ritual* (= L. 2679), rituals of Regular Offerings (dug4-ga i-sa-rí / i-sa-i), and the so-called ‘a:tu5 ritual’Note 25.

The first ritual includes four key elements (cf. Bonechi 1989):

- the presence of the 'purification priest' A:NAGA = a:tu5;

- an offering to the god dKU-ra performed by a priest with the title 'pa4:šeš (= pašišu) dKU-ra';

- the association of 2. to dug4-ga i-sa-rí, probably an offering consisting of garments and wool;

- the attestation of the term da-mi-mu ('reciter, lamenter').

After a discussion on the Regular Offerings-ritual, the author moves to the analysis of the ‘a:tu5 ritual’; specifically, the scholar underscores what follows: “The presentation of the main elements of the so-called a:tu5 ritual prompts the legitimate question of whether all these segments belong to one ceremony, even though they are registered in the MAT reports as separate items. […] I think it would not be wrong to join Bonechi (see Bonechi 1989) in stating that they are parts of the same ceremony and that it probably took place in the temple of the Ebla patron deities” (p. 221).

David anointed King over Israel; see 2 Sam 5:3; cf. 1 Sam 16:1-13 (retrieved March 14, 2021, from FCIT)

The fourth, and last, interesting elemet of Syrian cultic tradition involves Eblaite and Ugaritc rituals performing other purification rituals and, most noteworthy to the present comparative discussion, the anointing* of the head ritual (which sometimes follows a previous purification).

These two (sometimes connected) rituals are analysed in Viganò 2000, a follow-up paper to his earlier ‘Rituals at Ebla,’ [Viganò 1995]).

In this contribution, the author describes the ritual text TM 1730 (cf. supra), comparing this document with other purification rituals, such as the ‘ì-giš sag ritual’, whose actual performance has been considered by some scholars as a proper ‘purification ritual’, while others have advanced the interpretation of a purification ritual performed before the anointing* of the head.

A further comparison is presented with the sikil-ritual, ‘the purification, cleansing ceremony’, displaying texts from the Royal Archives of Ebla.

The author specifically reconnects the a:tu5-ritualNote 25 to the crowning ceremony of the new king (‘en’) at Ebla: the ‘ì-giš sag-ritual’ concerns the use of oil (ì-giš, lit. ‘sesame oil’), during the ritual action of the anointment of the new enthroned king (a practice well attested both in the Bible and also in the sacral consecration of a new bride of Egyptian pharaohs, such in the case of the first Hittite marriage between Ramses II and a daughter of the Hittite king Ḫattušili III (named in Egyptian Maatḥorneferure), see e.g. text KUB XXVI 53 (CTH 735), and also in the Amarna correspondence, in a letter between Amenḥotep III and Tarḫundaradu, king of Arzawa (CTH 151 = EA 31). This practice of anointing the head of the new king was perpetrated during the Middle Ages, when a new sovereign was anointed by the Pope with the sacred Chrism, a ritual also well known as for the baptism in the Catholic Church tradition (see e.g. The Catechism of the Holy Church, under no. 1241). The author reports some instances when the performing of the anointment ritual was the topic (pp. 16-18). In some cases, a similar ritual was applied to funerary ceremonies, too, as described on pp. 18-19.

Other ‘cleansing ceremonies’ practised at Ebla, called ‘sikil’-ritual(s) are taken into acoount: “Almost all the examples referring to this ritual are derived from the ARE reports that register the amounts of gold and silver used to manufacture objects offered to different deities during the illness of some important member of the Ebla upper class” (p. 21). “‘The anointing of the head’ (ì-giš sag-ritual) is not restricted to use in a funerary ceremony. Such a practice is performed for weddings and other occasions in which oil does not play the role of a cleansing element but is part of a ceremony of joy and celebration. Finally, the ‘purification’ (sikil) is performed in cases of illness that sometimes ended in death” (p. 22).

Back to top: Rituals in the Ancient Near East and Israel

Notes

- Note *: * (with no active hyperlink) is here used to mark a word or passage which is considered as a reference to other passages or words (the latters being marked with an * with active hyperlink; cf. infra, Note 7). Back to text

- Note 1: henceforth also abbreviated ANE. Back to text

- Note 2: the symbols (+) and (-) stand here for a presence or absence of a certain phaenomenon in ANE's or Israel's cultural and religious traditions. Back to text, a; Back to text, b

- Note 3: on this topic, cf. also the MONOGRAPH on Necromancy [PAGE UNDER CONSTRUCTION]. Back to text

- Note 4: also available in online version. Back to text

- Note 5: only the titles of the sub-paragraphs are here reported; for the full text, see here. Back to text

- Note 6: only the titles of the paragraphs are here reported; for the full text, see here. Hittite rituals (and mostly those of the Imperial Period, ca. 1350-1180 BC) are very interesting because most of them derive from a Hurrian milieu deeply rooted in ancient times (reaching also the period of Urkesh/Tell Mozan). Back to text

- Note 7: I report here only some selected passages useful to a critical comparison with ANE ritual practices; the complete excerpts can be found here). In this section, the symbol * is used to offer hyperlinks to the previous sections on ANE or on Giorgio Buccellati's critical view, allowing an easy comparison of some similar or antithetical practices. Back to text

- Note 8: for a comparison between worship towards God in opposition to worship of (pagan) idols, see e.g. the entry "Worship, Idol-" on the Jewish Encyclopedia). Back to text

- Note 9: on this topic, cf. also the related entry on the Jewish Encyclopedia). Back to text

- Note 10: this concept of "tributes" applied to ritual offerings can be maybe compared to ANE and also Egyptian tradition of presentation of "tributes"[/"tax"] (gun mada/niŋ2.gu2.DU (in Sumerian); bāru/biltu/kubtu/ma(d)datu [et al.] in Akkadian; jn.w [et al.] in Egyptian [to access the latter hyperlink, you need to click a first time on the hyperlink; there you will be asked to login as "guest"; afterwords, you can click on the same hyperlink a second time, reaching the webpage to lemma-no. 27040]) to the king (noteworthy since God can be here seen as a king*). Back to text

- Note 11: on this topic, cf. also the entry "Liturgy" on the Jewish Encyclopedia). Back to text

- Note 12: on this topic, cf. also the entry "Ṭaharah" on the Jewish Encyclopedia). Back to text

- Note 13: on this topic, cf. also the entry "Priestly Code" on the Jewish Encyclopedia). Back to text

- Note 14: important to note that also in Mesopotamia (and in Egypt) a specific ritual aimed at sacralize a cultic object, usually a statue, through a specific ritual known as "opening of the mouth" (pīt pī) or "washing of the mouth" (mīs pī) [see here for the related entry on the RlA]; more specifically, they are two different rituals or, at least, two stages of a single cultic act. It is also remarkable that a similar ritual is attested in Egypt (the "Opening of the Mouth Ritual", OMR) which served to some extent the same purpose (even if it was also performed on the body of a dead person in order to guarantee him/her the possibility of an active and "living" afterlife). Back to text, a; Back to text, b

- Note 15: on this topic, cf. Buccellati 2006, "On (e)-tic and -emic", Backdirt (Winter 2006), pp. 12-13. Back to text

- Note 16: for the links to the Thesaurus Linguae Aegyptiae, please remember to click a first time on the hyperlink; there you will be asked to login as "guest"; afterwords, you can click on the same hyperlink a second time, reaching the webpage to lemma. It is noteworthy that Egyptian and Hittite languages (despite the former is Hamito-Semitic, while the latter is Indo-European) share the same root for "house" > "temple" (i.e. "house [of the god]"). Back to text

- Note 17: literally, "the lady/sister for the god" (where "-ra" is the Sumerian suffix of the dative [see e.g. Edzard 2003, p. 40]). Back to text

- Note 18: cf. Giorgio Buccellati's idea about the ethos of creation*. Back to text

- Note 19: this passage helps in clarifying the distinction between "common offerings" and "sacrificial offerings" (requiring a "formal presentation"). Back to text

- Note 20: see CTH 264: Instruktionen für Priester und Tempelpersonal. Back to text, a; Back to text, b; Back to text, c

- Note 21: see e.g. the scenes portrayed on the Hüseyindede vase A and Hüseyindede vase B, on the İnandık vase, or on the walls of the South Gate of Alaca Höyük. Back to text

- Note 22: on the specific case of "necromancy" (discussed in Gane, p. 250, here not reported) see the MONOGRAPH Necromancy [PAGE UNDER CONSTRUCTION]. Back to text

- Note 23: about "anoiting" cf. also the related section 6 on "Cultic Rituals at Ebla/Tell Mardikh"*. Back to text

- Note 24: On rituals and worship in Ancient Near East and the Bible, see e.g. Achtemeier 1996. Back to text

- Note 25: The interpretation of the term a:tu5 is questioned if as referring to a priest or to a lustration ritual; the same term could both mean "an 'atua' priest" or "an 'atua' purification ritual"). Back to text, a; Back to text, b

Back to top: Rituals in the Ancient Near East and Israel