Back to top: Transitivity, intransitivity

The gods as intransitive

In several places in the current website we have pointed out the metaphor coined by Jacobsen and used by Buccellati regarding “transitivity”. Jacobsen used the term in several articles of the 1960s and 1970s, including “Formative Tendencies in Sumerian Religion” (1961). In this text, Jacobsen wrote that “It is characteristic for Sumerian religion, especially in its older phases, that the human reaction to the experience of the numinous remained singularly bound by the situation in which the numinous was encountered, and by some central phenomenon or group of phenomena in it particularly. The numinous appears to be immediately and unreflectingly appreheded as a power in, underlying, and willing the phenomenon, as a power within it for it to come into being, to unfold in this its particular and distinctive form. In consequence the phenomenon largely circumscribes the power, for the numinous will and direction appear as fulfilled in the phenomenon and do not significantly transgress it. This boundedness to a phenomenon one might describe with a grammatical metaphor as intransitivity.” (p. 2)

Jacobsen’s ideas on transitivity were first expressed in the Haskill lectures he gave on the figure of Dumuzi/Tammuz at Oberlin College in the early 1950s. The article “Towards the Image of Tammuz” (1962) contains a rewritten version of the final lecture in that series. It is not, Jacobsen clarifies, that Tammuz as power in the milk dies when the churn and the cup are empty, or that Tammuz as the power in grain dies when the grain is crushed between millstones. Rather, it is that the Tammuz-power “does not, either in action or as will and direction, ever transcend the phenomenon in which it dwells.” (T. Jacobsen, “Toward the Image of Tammuz”, History of Religions, Vol. 1, No. 2 (Winter 1962), p. 191.) Tammuz does not act on anything or anybody, his activity dissolves into the contrast between being and not being, living and dying. In the spring, the power “is there”. In the winter, the power is absent. The power inheres completely in the phenomena that manifest it, which makes Tammuz a poor helper to needy humans. In fact, Jacobsen points out that very few prayers are addressed to him (“Towards the image of Tammuz”, pp. 74-78). At most, he seems a delightfully self-centered youth.

Jacobsen contrasts this view of things to the wider range of activity and power in other members of the Mesopotamian pantheon, such as Enlil, Enki, and Ninurta. These three gods are also connected to specific phenomena—storms, sweet waters, and thunderclouds, respectively—but their activities are broader. They can be of help or remain silent; create or destroy; they make demands and enforce them. They can be prayed to, and Jacobsen describes them as “transitive active” powers.

The metaphor appears again at the beginning of Jacobsen’s Treasures of Darkness (1976) to refer to the characteristic of deities who “made no demands, did not act, merely came into being, [were], and ceased being in and with [their] characteristic phenomenon.” (Treasures, p. 9) In this context, Jacobsen further points out that this characteristic was common to the older strata in the Mesopotamian pantheon, and contrasts with the younger gods who had power and interests beyond their defining characteristic phenomenon. Again, Jacobsen presents Dumuzi as an “intransitive” figure of the power of fertility and new life in the spring, and writes that “there is no instance in which the god acts, orders, or demands; he merely is or is not.” (Treasures, p. 10)

Later gods such as Marduk present elements of personal activity, or “transitivity”, that can be contrasted with the passivity Jacobsen emphasizes in the figure of Tammuz.

Back to top: Transitivity, intransitivity

Buccellati’s proposal

In his extended comparison of Mesopotamian and Biblical spiritualities, Giorgio Buccellati extends the transitivity-intransitivity metaphor and elevates it to a category that describes not only a moment in the process of development of Mesopotamian religiosity, but that defines the gods in general.

In chapter 7.3 of When on High the Heavens, Buccellati presents an alternative between “whether one sees the absolute as the subject or as the object of the relationship that is perceived by individuals and by human groups in their intuition of the absolute.” Furthermore, “the two terms (subject and object) are to be understood in the syntactic sense of what governs a predicate or is governed by it, with the consequence that the nature of the absolute radically changes the nature of the predicate itself, as follows. In Mesopotamia, we can say that the predicate is intransitive, because the absolute (subject or object) is not conceived in a personal way. As such, it is not really the term of a relationship that is based on a face-to-face encounter. The Mesopotamian absolute does not look us in the eye, nor can human beings look him in the eye. Because, in fact, it has neither face nor eyes. This is how the absolute, seen as a profound immanence, qualifies the nature of the relationship. … In the biblical perception, exactly the opposite occurs. The relationship is transitive in the specific sense that there is a face-to-face posture that is, symmetrical with, if not on the same level as, the absolute conceived as God. This profoundly colors the nature of the relationship, and indeed changes its deep structure, even when there are strong similarities in external appearances.”

This long quotation serves to point out Buccellati’s enrichment of the distinction that Jacobsen indicated with the word “transitivity”. Not only is there an axis regarding action being done to a subject, but there is also an axis regarding the personal nature of the action done, the “face-to-face” posture mentioned above.

Buccellati considers the difference between transitive and intransitive versions of the divinity as indicative of a radically different religious structure in Mesopotamia and in the Biblical world. The burden of his study and this accompanying website is to provide evidence of this difference.

Back to top: Transitivity, intransitivity

Development from intransitivity to transitivity?

The difference described by Jacobsen could be a moment in development from intransitivity to transitivity, as he seems to imply. Interestingly, the later gods (who are also closer in time to the formation of the biblical texts) exhibit more personal activity than the earlier gods like Tammuz. Following Jacobsen’s logic, one could think of the biblical God as a rarefied and simplified version of what came before, but not as exhibiting a difference in kind.

However, such a conclusion might not explain one notable difference between the Mesopotamian and the Biblical religions. While Mesopotamia possibly moved toward a personal conception of the absolute, it was not sufficiently convinced of the power of that absolute to survive the fall of the social and political structures that held its culture together. The people of the Bible, on the other hand, notwithstanding utterly destructive events, continued to read their history through the lens of a personal relationship with a personal absolute. This fact supports Bucellati’s claim that together with deep similarities between the two cultures and religions, there is also a radical structural difference.

Back to top: Transitivity, intransitivity

Transitivity from a grammatical point of view

The grammatical term “transitivity” traditionally refers to a verb that acts through to a subject, often the direct object of the phrase. Thus “the lion ran” is intransitive, whereas “the lion ran after the tourists” is transitive: the action of running is aimed at an object.

Some linguists have proposed more complex understandings of the structure indicated with the term. For instance, Halliday proposes a further distinction between transitivity and ergativity, and places the focus more on the process and its initiator than on the type of verb used. Halliday points out that a great number of verbs can be used in both senses, transitive and intransitive, on the basis of their subordinate clauses. He notes that “these concepts relate more appropriately to the clause than to the verb. Transitivity is a system of the clause, affecting not only the verb serving as Process but also participants and circumstances.”(Halliday, Introduction to Functional Grammar, Routledge 2014, p. 226) Thus it is not so important to look at the verb as it is to look at the clause. Halliday suggests that “(i) generalization across process types and (ii) transitivity model are independently variable. In English and in many other languages, it is the transitive model that differentiates the different process types and it is the ergative model that generalizes across these different process types.” (Halliday, op. Cit., p. 334.) Halliday’s transitive model construes the actor as bringing about the unfolding of a process in time (p. 334), thus supporting Buccellati’s distinction between transitive and intransitive versions of divinity as a way to differentiate between an absolute who acts as a “person” (or “affecting presence“) with an unpredictable will, and an absolute which, like fate, simply “is” without acting or willing.

Back to top: Transitivity, intransitivity

A quantitative approach

If divine action can be construed as an “occurrence”, fate bringing about an event without will or finality, or as the action of a willing person, I wondered if it would be possible to find grammatical features of the religious texts of the two traditions, and thereby support one or the other interpretation.

Counterexamples to Buccellati’s claim exist in the Mesopotamian corpus. See for instance Enki and Ninmah: “Enki answered Ninmaḫ: I decreed a fate for the first man with the weak hands, I gave him bread. I decreed a fate for the man who turned back the light, I gave him bread. I decreed a fate for the man with broken, paralysed feet, I gave him bread. I decreed a fate for the man who could not hold back his urine, I gave him bread. I decreed a fate for the woman who could not give birth, I gave her bread.” (1.1.2 ETCSL) Clearly the god is “transitive” in this case: active, present and speaking in the first person. But taken as a whole, does the Mesopotamian corpus tend toward “intransitivity”, and the Bible to “transitivity”? If so, could a statistical difference be found in support of our hypothesis?

In order to find out, I wrote a program in Python to parse the texts of the Mesopotamian and Biblical religious writings into their dependencies. In the first iteration of the program, I used the SpaCy library as the basis of a parsing system that identifies the universal dependency labels of words with 87% accuracy. On the basis of this parsing, it was possible to read through thousands of lines of text, and filter and count several grammatical forms that might indicate the “transitivity” in discussion.

The first version of the program uses a logical structure as follows. If the name of a god is found in a sentence, the program considers several possibilities. If the name of a god is the subject of the phrase, and the head of the phrase is a verb, then it is considered a case of an “acting god”, and the direct object of the action is identified if possible. If the divine name is a passive subject, or if it is the direct object of the phrase, then the phrase is counted as a case of a “passive god”, where the divine is an object acted upon by some other actor.

The English translations of Sumerian religious texts in the ETCSL library, and the NRSV English translation of the Bible (excluding deuterocanonical and New Testament texts), were run through the program. The outputs include lists of subject, verb, object and complete phrase for error checking, and counts of how many times the divine name appears as active or passive. By normalizing (dividing by the total number of phrases containing the divine name), the two corpora are compared.

I found that there is not a great statistical difference in the presence of the two verb forms in the two corpora: by the definition of activity and passivity used, the Mesopotamian gods are 15.2 percent active, and 3.3 percent passive. By contrast, the Biblical God is 16.4 percent active and 3.0 percent passive. These figures marginally support the hypothesis that the Biblical God is more active than the Mesopotamian gods, but the difference is slight.

However, by searching for occurrences of the verb forms “to say” and “to speak” in phrases including divine names, a significant difference appears. Biblical texts of this form are nearly eight times more frequent: Mesopotamian gods speak 1.8 percent of the time, whereas the Biblical God speaks 14.2 percent of the time. This result tends to support our hypothesis, insofar as speaking is a quintessentially “personal” trait. Words do not merely appear; they are spoken by a person who decides to say them.

Back to top: Transitivity, intransitivity

Critique of first results

This initial program has several weaknesses, which professors Mauro Giorgieri, Marco Passarotti, and Maria Freddi have helped me see and improve. First, it operates on English translations instead of on original texts. To some degree, this causes imprecision. However, whatever imprecision is introduced in this manner presumably affects both corpora equally.

A more serious problem is that the binary opposition between phrases in which the god is the subject of a verbal clause, versus phrases in which the god is the object of the verbal clause, does not entirely capture the difference we have called “transitivity”. Some direct forms of speech would be correctly classified: “God speaks to man” while other equivalent phrases such as “man is spoken to by God” would not. Further, some Mesopotamian texts recount conversations among gods: “Ninurta spoke to Enlil”. In this case, should the god be classified as active or passive? Clearly, our first system is not able to generate robust conclusions, and to date we have not been able to improve the specificity of the decision tree in the program.

Back to top: Transitivity, intransitivity

Comparing Shuila prayers with the Psalms

A second attempt at comparison dealt with two smaller corpora: the Shuila prayers from Mesopotamia, and the book of Psalms from the Bible. As has been remarked by several scholars, the two corpora are similar in intent and use, as well as in length and to some degree in style. As with many Mesopotamian texts, the shuila prayers are quite fragmentary in many cases, but they do contain enough text to make statistical comparison possible.

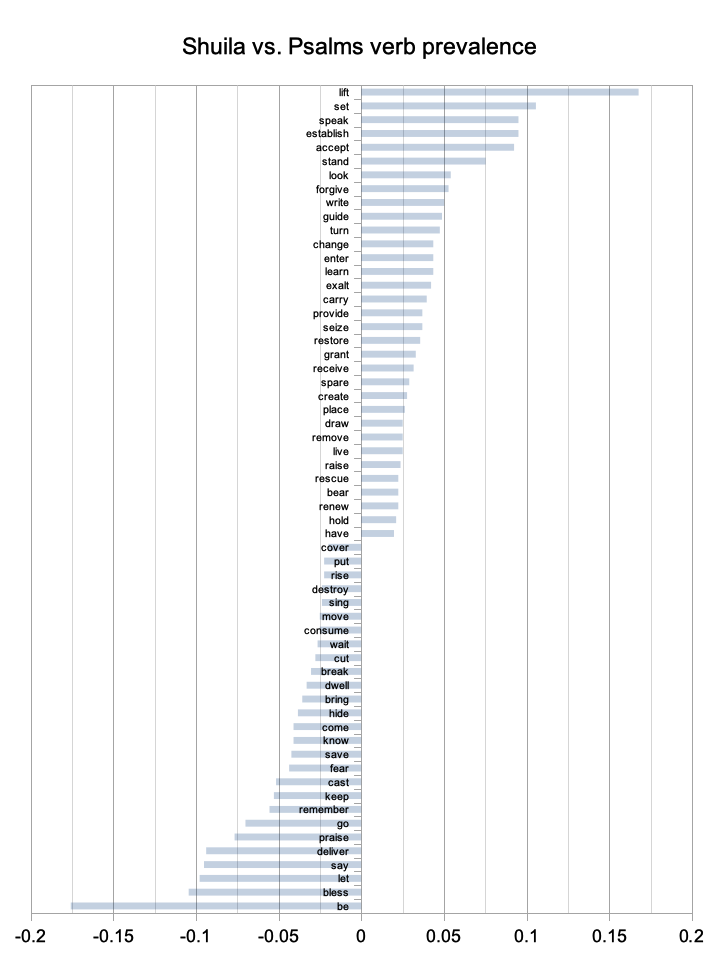

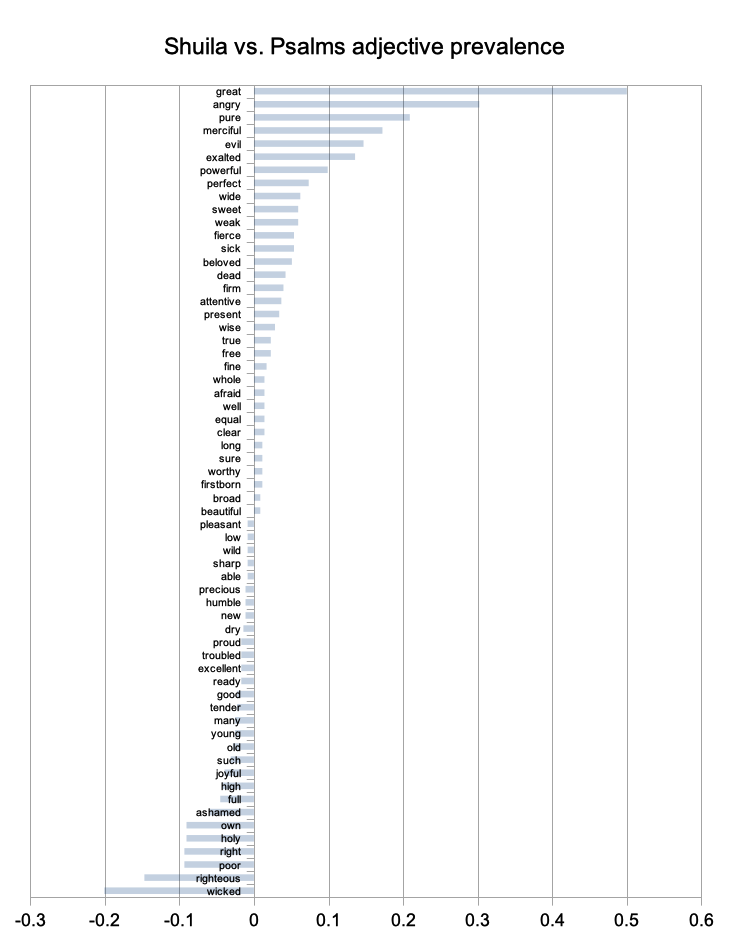

Again we used the NRSV translation of the Psalms, and compared it to the entire catalog of Shuila prayers collected by prof. Alan Lenzi on his shuilas.org website. We examined the typical language of each corpus, irrespective of speaker. All verbs and adjectives were extracted, lemmatized, counted, normalized on the basis of corpus length (number of each verb / total number of verbs extracted), and graphed for the 60 verbs and adjectives that showed the greatest difference between corpora, which we call “prevalence”. Words for which either corpus gave zero results were excluded from the calculation of prevalence.

Back to top: Transitivity, intransitivity

Verb prevalence

Results for verbs are in the figure below in a keyness graph. (Shuila prayers are right of the axis, psalms to the left).

Fig. 1

“Lift”, which is the meaning of the term “shuila” and appears in nearly every shuila prayer, can be excluded from significance. In the Psalms, “be” is quite frequent, but the meaning of this fact is obscure. “To be” is a common helping verb, as well as an indicator of state. “Say” and “speak” appear at opposite extremes, which might indicate a stylistic difference in translation, or it might indicate a more profound difference, but it would be necessary to examine each occurrence to reach a specific conclusion.

After removing these words from the list, we see that in the Psalms, the next most prevalent verbs are bless, let, deliver, praise, go, remember. The correspondingly prevalent words in the Shuila prayers are set, establish, accept, stand, look, forgive. A case could be made for some difference in the relationship to the god on this basis, but it would not be strong. One would have to account for stylistic and translational differences, and it would not be easy to arrive at any conclusion regarding “transitivity” on these grounds. One might simply be comparing apples and oranges.

Back to top: Transitivity, intransitivity

Adjective prevalence

Relative adjective frequency is shown below (Shuila prayers are right of the axis, psalms to the left):

Fig. 2

In the case of the adjectives, some evidence might be deduced from the importance of moral terms in the psalms. “Wicked” and “righteous” set up an alternative common to the psalms, and emphasize the concept of a moral choice, while the shuila prayers emphasize the condition of the person praying as being in need, but not as having offended the gods with his actions. The Mesopotamian image of god, at least as shown by the prevalence of the adjective, emphasizes “greatness”, which is not connected to the will. It is often used as a captatio benevolentiae in order to obtain the desired favor.

Back to top: Transitivity, intransitivity

Concluding remarks

Our explorations tend to confirm Buccellati’s affirmation that for the people of the Bible, God is a person who has a will and is active, while in Mesopotamia, man speaks to the god as to a technician, and expects a specific response that is not freely given or withheld, but is rather the result of a correctly executed human prayer and ritual. This difference can also be described in terms of the different structure of the prayers and divination rituals (see theme on ritual). As alluded to above, see also Armstrong’s work on the “affecting presence”, which offers another way to render the difference we have ascribed to transitivity.

Back to top: Transitivity, intransitivity